Post n°232. The recent rise in French inflation is temporary in nature but could last for a few more quarters. It is linked to a normalisation of prices after the lows seen in 2020, and to the increase in industrial goods and energy prices. After reaching a peak on the back of these temporary effects, inflation should come back to below the 2% mark over the course of 2022.

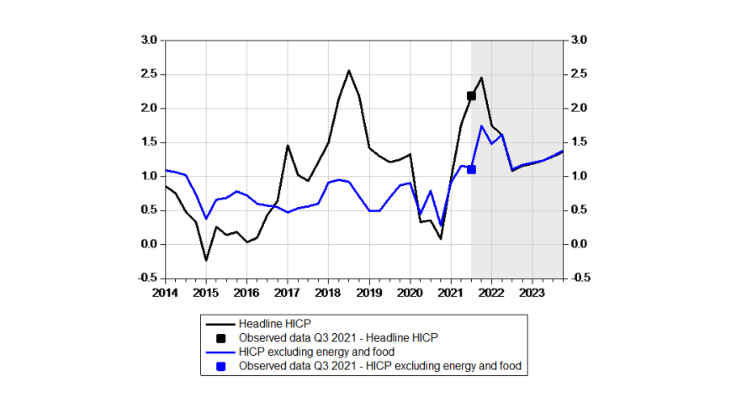

Source: INSEE data up to the second quarter of 2021 and for the data point in the third quarter of 2021. Shaded area shows Banque de France projections. For the third quarter, only the inflation figure for July was available at the time of the projections

French inflation has risen sharply since the start of the year

Changes in French consumer prices are monitored using two indices: the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), which is compiled using a harmonised methodology to ensure comparability between euro area and European Union countries; and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) which is the one more commonly used in France. According to provisional data, French annual HICP inflation stood at 2.7% in September while HICP inflation excluding energy and food stood at 1.7%. These figures, as well as those for the month of August, are in line with the Banque de France inflation projections published at the start of September, for which only the inflation figures for July were available. French inflation thus remains below the annual rate for the broader euro area, which in September was estimated at 3.4% for headline HICP inflation and at 1.9% for HICP inflation excluding energy and food. Another notable feature of the French inflation figures is that manufactured goods inflation is particularly high, at an annual rate of 0.8% in the third quarter, compared with an average of 0.0% for the years 2010-20.

CPI inflation is generally slightly lower than HICP inflation (0.15 percentage point lower on average), but the gap between the two has widened significantly since the second quarter of 2021. CPI inflation stood at 2.1% in September, well below the 2.7% reading for HICP inflation. The difference stems notably from the fact that energy products carry a higher weight in the HICP consumption basket (counterbalanced by a lower weight for health costs, as the HICP only takes into account costs borne by consumers, and not those reimbursed or paid by the social security), and their prices have risen sharply.

These figures raise the question of whether we are seeing a lasting return of inflation. The future path of prices will be influenced by two dynamics, each with a different time horizon. The current rise in inflation is almost certainly temporary, although it could last for a few more quarters. It reflects a normalisation of prices after the lows reached in 2020, as well as the rise in energy and manufactured goods prices. Over the longer term, however, the economic recovery should trigger a more durable rise in inflation for the general level of prices and wages.

The high rate of inflation in 2021 is partly explained by a normalisation of prices after the steep falls in 2020

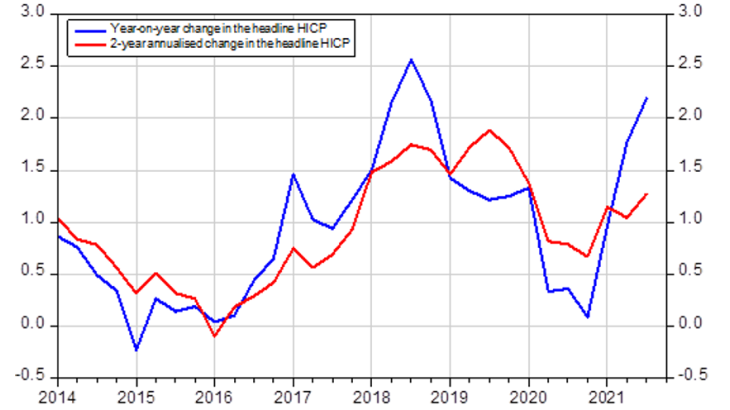

In France, the rebound in the HICP since the start of the year partially reflects base effects in energy and services prices, which are by nature temporary. In 2020, oil prices fell sharply, while lockdown measures triggered a steep drop in the consumption and prices of services, in particular for private services such as transportation and accommodation. Calculating the year-on-year change in prices with reference to these very low levels leads mechanically to a high rate of inflation. The impact of this base effect on the headline HICP can be seen when we compare the year-on-year change with the annualised change over a two-year period (Chart 2): in the third quarter of 2021, the HICP was 2.2% higher than in the third quarter of 2020, but only 1.3% higher than in the third quarter of 2019 on an annualised basis, which is close to its pre-Covid trend.

Source: INSEE.

The sharp rebound in energy prices is feeding through to inflation

In addition to the rise in oil prices caused largely by the base effect described above, there has also been a surge in gas prices since June 2021, with retail prices (as measured in the HICP) up 27% year-on-year in August 2021. Regulated electricity prices should see a more limited rise of 4% in February 2022, partially reflecting the sharp jump in wholesale prices. Part of the inflation caused by these prices rises is temporary. Indeed, futures markets for natural gas are currently pricing in a sharp decrease in prices in the second quarter of 2022, once the current high demand related to stock replenishment and the winter season is over. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that these pressures might last slightly longer. Moreover, in the future, energy transition policies could push up the relative prices of these high-carbon energy products, although the impact on inflation should be limited in France’s case as its national electricity production emits low levels of CO2.

The rise in non-energy inflation reflects pressures on industrial goods prices, caused by tensions between supply and demand following the reopening of the world economy

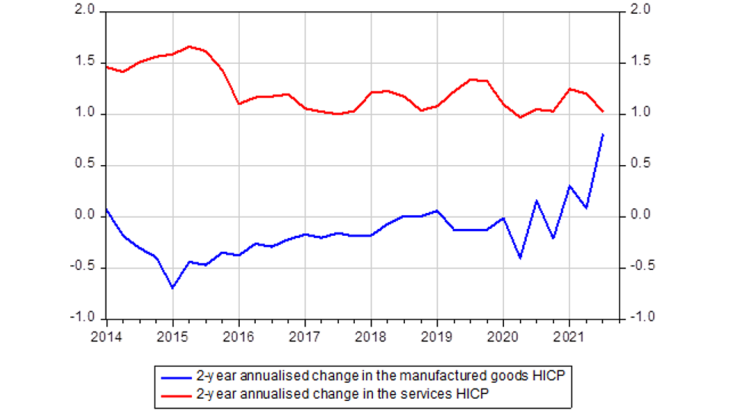

The reopening of the world economy has led to a sudden recovery in demand, but with a shift towards the consumption of goods rather than services, as health restrictions and changes in behaviour are continuing to weigh on the services sector. At the same time, with inventories running at particularly low levels, global supply chains have been hit by bottlenecks which have been further exacerbated by logistical problems, for example in container shipping, and by production difficulties for inputs such as semiconductors. This has led to a surge in global raw material and industrial input prices, which has in turn been feeding through to manufactured goods prices. As a result, French manufactured goods inflation accelerated sharply in the third quarter of 2021, to 0.8%. Even when measured on an annualised basis over two years (to cancel out the base effects linked to the 2020 Covid shock), manufactured goods inflation has accelerated markedly, in contrast with services inflation (Chart 3).

Source: INSEE.

Will the current rise in inflation prove long-lasting?

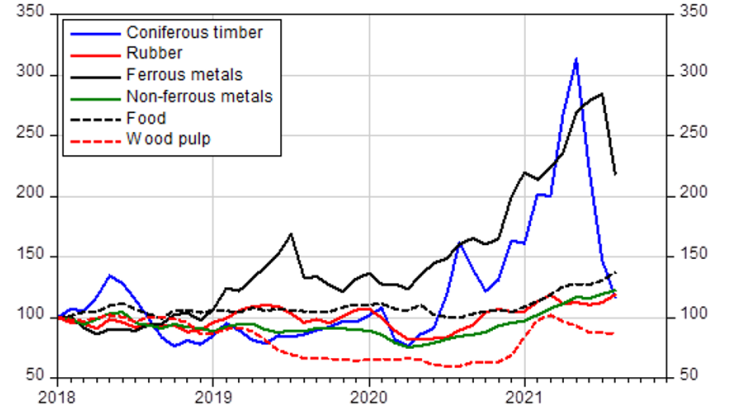

The rise in industrial input and raw material prices has proved stronger and more persistent than anticipated. Indeed, it is very difficult to predict when inflation will peak. Certain prices, such as those of timber and ferrous metals, have already passed their peak and are falling sharply. Others, such as those of rubber, non-ferrous metals and agricultural commodities, are continuing to rise (Chart 4). Some analysts also fear that production difficulties in the semiconductor sector could last for a few more quarters.

Source: INSEE.

There is also an opposite risk: previous episodes of sharp rises in manufactured goods prices (2002-3 and 2011-12) were followed by falls that weighed on headline inflation. In addition, a possible slowdown in Chinese growth, linked notably to problems in the real estate market, could trigger a fall in construction activity which would in turn weigh on global raw material prices.

Based on these different factors, the Banque de France projection published in September sees inflation peaking at 2 3/4% at the end of 2021, and then dropping back again in 2022. The main risk to this projection is that the current rise in inflation could prove stronger and more persistent. After falling back, inflation should resume its upward trajectory in 2023, albeit at a more gradual pace (Chart 1), averaging 1.3% over the full year 2023.

In the context of the economic recovery, and once the temporary upward pressures have faded, inflation should resume a slight upward trajectory in 2023, while remaining below the 2% mark

The temporary effects described above could last for another few quarters, but once they have passed, inflation should mainly be shaped by a second dynamic: the gradual acceleration in the general level of prices and wages, linked to the strength of the labour market. The recovery in activity, and especially in employment, should gradually pass through to wages and prices. While the first dynamic concerns energy and manufactured goods prices, and is moving rapidly due to the sudden surges in raw material prices, the second dynamic also concerns services prices and is likely to be more gradual.

In this second phase, wages will react both to observed price rises and to the recovery in the labour market. This reaction could be amplified by hiring difficulties, which are currently being experienced by a large number of firms. The pass-through of wages to prices will depend on the evolution of corporate profit margins, which are currently very high. Prices and wages will also depend on the path of households’ and firms’ inflation expectations. Medium-term expectations, measured using inflation-indexed financial instruments, had fallen to under 1% for the euro area at the start of the crisis. They have since risen again, but remain well below 2%.

The Banque de France’s projection is for French HICP inflation of 1.3% in 2023. The European Central Bank’s 2023 projection for the euro area is 1.5%. Even taking into account the uncertainties over the duration of the temporary factors and the future path of wages, the most likely scenario is that inflation will remain below 2% in 2023 in both the euro area and France.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024