Climate change is likely to put upward pressure on commodity prices. Indeed, climate change is increasing the intensity and frequency of severe weather events, affecting agricultural yields and ultimately the price of food commodities. Similarly, the energy transition is likely to weigh on commodity prices by shifting demand towards equipment that requires large amounts of raw materials (e.g. electric vehicles, wind turbines).

Faced with these growing risks on commodities, it is worth looking at the way in which firms deal with them: how do firms cope with shocks to commodity prices? What are the consequences of commodity shocks in terms of profitability, productivity or credit risk? Answering these questions enable to better assess the ability of firm to cope with the climate transition and, more broadly, with commodity shocks, whatever their origin (energy crisis, natural disasters).

To address these issues, I focus on the raw-material-intensive sectors (manufacturing). However, each sub-sector consumes very specific raw materials: agricultural raw materials are mainly consumed by the food industry and not by metallurgy. So, I focus on shocks that directly or indirectly affect all raw materials, and thus all manufacturing sectors, namely shocks to fossil commodities. Indeed, most raw material production depends on fossil resources. Then, I build a shift-share instrument to explain the dynamics of firms’ financial ratios: the share part of the instrument (the exposure) is the firm’s dependence on raw materials. The shift part (the shocks) are fluctuations in crude oil spot prices.

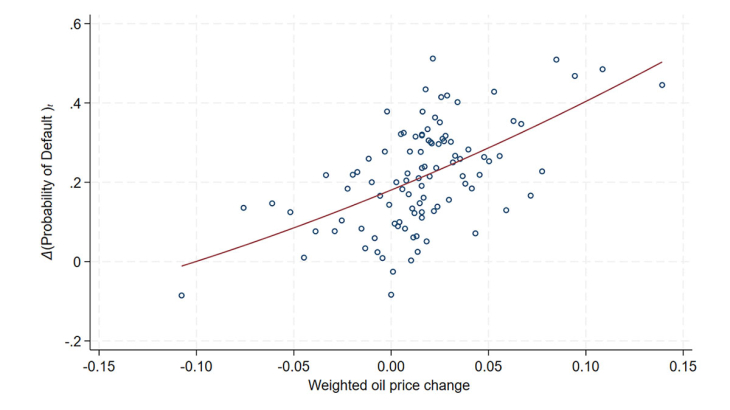

Based in this framework, I show the impact of oil price shocks to key financial and operational metrics, including value added, employment, real wages, labor share, profit margins, dividend payments, productivity, and credit risk (see Figure 1). I highlight the asymmetric effects of oil price increases and decreases. A one standard deviation increase in the weighted oil price shocks leads to a €396 decrease in per capita productivity (in 2024 euros), and a 0.30 percentage point increase in the probability of default, while there is no significant effect in the case of oil price decreases, leading to persistent effects of oil price increases in the medium term. I also show heterogeneous effects of oil price increases across firm size and energy intensity.

This paper has implications for policymakers, especially those concerned with financial stability, competitiveness, and more generally for those studying climate transition risks.

Keywords: Oil Shock, Oil Price, Raw Materials, Value Added, Wage Bill, Labor Share, Profit Margin, Default, Productivity, Climate Risk, Transition Risk, Physical Risk, Credit Risk

Codes JEL: E32, G3, G33, G35, Q41