The economic literature reveals a lack of consensus among economists and policy-makers concerning the impacts of climate change and the appropriate policies to face this risk. This lack of consensus partly explains the lack of coordinated ambitious policies. As underlined by Nordhaus (2019), “Humans clearly have succeeded in harnessing new technologies. But humans are clearly failing, so far, to address climate change”. This is why applied work is important to understand better the different mechanisms behind climate change and carbon taxation, along with the key area of disagreement among experts.

Our contribution is to propose fully transparent and free-access model, the Advanced Climate Change Long-term model (ACCL), with a rich and endogenous modelling of the GDP growth dynamics. It is a user-friendly projection tool, designed with R-Shiny, which allows the user to run scenario-analysis to identify and quantify the consequences of energy price shocks on TFP. The user can change at will all the hypotheses and parameters. Thus, a sensitivity analysis can be carried out, in order to test, on a long-term horizon, the dependence of the results to each parameter and for different specifications. Besides, it also helps to understand the main economic and environmental mechanisms of both climate change and carbon taxation, as well as the reasons behind the current lack of consensus among economists. It can also be used in the context of stress test exercises by financial institutions.

In this model, we assess the long-run effects of carbon taxation on economic growth through two opposite channels. First, the negative consequences of carbon tax, or any other regulation increasing prices of CO2-emitting energies, on growth via the impact of higher energy prices on Total Factor productivity (TFP). Then, the positive economic impact of limiting climate change consequences, through the abatement of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (as the increase in the prices of CO2-emitting energies has a deterrent effect on their consumption). As the net impact is most likely to be context dependent, it is also interesting to study the structural conditions under which one effect dominates the other.

To address this question, we build an original and extensive database that enables us to estimate or calibrate most of the relationships of the model. It gathers panel data for 19 developed countries and six emerging countries among the world greatest polluters, plus six regions to cover the rest of the world on many economic, energy and environmental variables (such as the employment rate, the average years of education, the market regulations, the relative price of energy or the CO2 emissions...). We then use these empirical findings to implement-global and local projections for the whole world, decomposed in 30 countries and regions at the 2060 and 2100 horizons, allowing for user-designed scenarios of both climate change and carbon taxation.

This tool is based on a supply-side approach. Its main added value lies notably in the endogenous modelling of TFP, capital and Gross Domestic Product (GDP), together with the estimation and calibration of most of the relationships on an extensive panel of data. TFP, which is a major source of uncertainty on future growth, is determined by relative energy prices, investment prices, education, structural reforms and decreasing returns to the employment rate. The comparison of two distinct and broad time horizons (2060 and 2100), as well as the worldwide scale of the analysis enables us to examine the role played by both the time horizon and international coordination in the outcome of the climate policy. The climate policy assessed in this paper corresponds to a Pigouvian tax on CO2 emissions.

We mainly concentrate here on GDP damage, but non-market damage (migration, conflicts, biodiversity loss…) should also be considered, as most of them are outside the scope of our supply-side, long-run GDP approach, although constituting some of the most significant consequences of global warming.

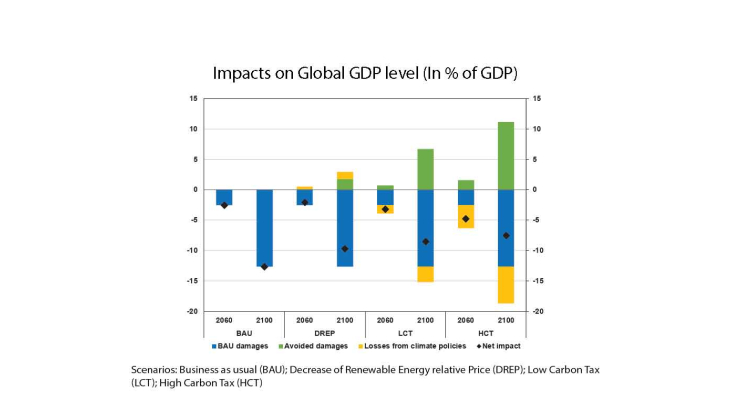

We implement four scenarios. In the BAU (for Business As Usual) scenario, we assume no carbon taxation and so, we set the annual evolution of the relative price of each energy type to zero for the whole world from 2017 to 2100. The DREP (for Decrease of Renewable Energy relative Price) scenario is identical regarding all the different CO2-emitting energy sources, but it displays an average annual decrease of -2% for the relative price of non-CO2-emitting electricity in the entire world and over the whole time period. This decrease in the relative price of renewable energies may correspond to the effect of a subsidy or of technological progress, which reduces their production costs. With the LCT (for Low Carbon Tax) or HCT (for High Carbon Tax) scenarios, we introduce a climate policy that raises annually the relative price of coal, oil, natural gas and CO2-emitting electricity by 1% for LCT and 3% for HCT, in each country / region, for the whole period. On the contrary, the “clean” electricity relative price does not change in these two scenarios.

The outcome of these scenarios is presented in the graph below. Our results illustrate this “tragedy of the horizon” with net GDP losses induced by climate policies in the medium term, but a favourable net impact in the long term, thanks to the avoidance of greater climate damage. Similarly, we can presume that international coordination is of significant importance since pollution and the resulting climate change are global issues. A collective reduction of greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions would actually benefit a vast majority of countries. Yet, these social benefits can be neglected by national governments facing high individual costs to implement such a policy and fearing inaction by other emitters. Our simulations do show that for each country, the best individual strategy is a “Business As Usual” (BAU) one and stringent climate policies for others.

The global best collective strategy would be the implementation of stringent climate policies simultaneously in all countries. This coordination problem comes from the fact that a climate policy has a detrimental impact on GDP through TFP decrease in the country which implements it, but a favourable GDP impact through lower environmental damage for all countries. It means that the collective interest is the implementation of coordinated stringent policy, but that each country has interest to free-ride.