- Home

- Publications and statistics

- Publications

- Japan: when full employment does not equ...

Japan: when full employment does not equate to wage growth

Post n°89. Despite full employment, Japan is struggling with wage stagnation. Although this "enigma" can in part be explained by cyclical factors - subdued productivity and inflation expectations - it is also being exacerbated by structural factors linked to the country’s social model, notably the duality of its labour market. As a result, the prospects for a rise in wages and hence inflation remain limited.

The low rate of wage growth contrasts with the tightness of the labour market

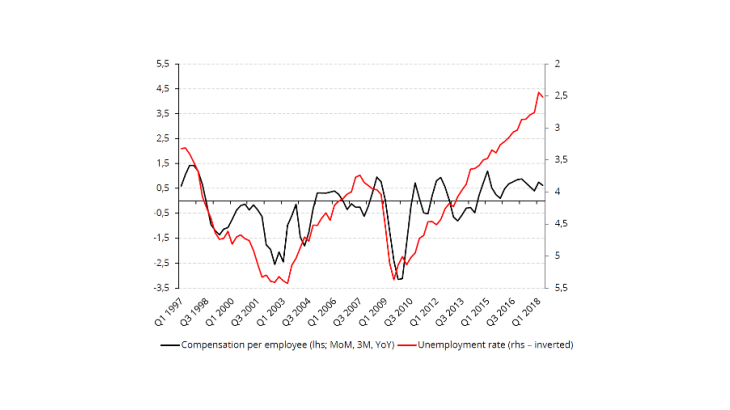

The Japanese labour market is under pressure: after declining steadily since 2009 (see Chart 1), the unemployment rate today stands at 2.5%. Although Japan tends to have less unemployment than other advanced countries – the OECD estimates its structural unemployment rate at 3.6% compared with 8.9% in France and 4.5% in the United States – the current low level indicates that employers are experiencing major recruitment difficulties.

Despite this, however, nominal wages have only risen to a limited extent (+0.8% in 2017). Japan's wage growth is also low in relative terms, when compared with rates in other advanced countries facing labour market tensions (+3.1% in the United States in 2017) or with the rates observed during previous periods of full employment. Even more worryingly, whereas wages and unemployment were in the past correlated, a disconnect appears to have emerged since 2014 (see Chart 1).

Subdued productivity and inflation expectations are weighing on wages

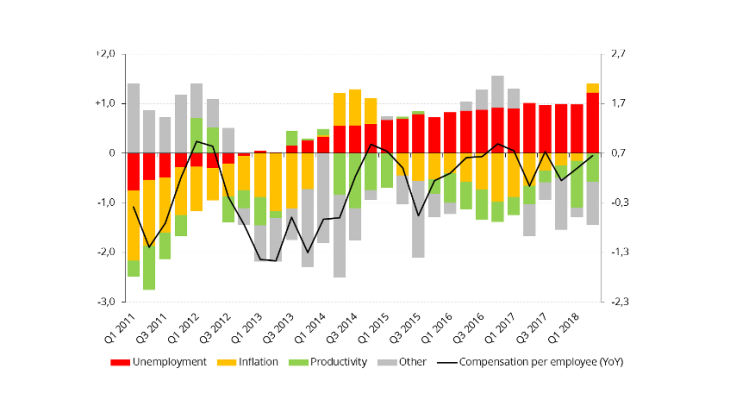

A first possible explanation is that Japan's anaemic wage growth stems from a flattening of the Phillips curve, i.e. a decline in the sensitivity of wage dynamics to the unemployment rate. However, estimations carried out on G7 countries show that the link has remained strong and stable since the 1990s (BdF, 2018). The reduction in unemployment over recent years has indeed pushed average compensation per employee upwards (+0.8 pp on average since 2014, see Chart 2).

The causes of Japan's sluggish wages must therefore lie elsewhere. Wage growth has notably been dampened by subdued inflation expectations (average contribution of -0.5 pp over 2011-2018). Low productivity growth has also played a role – albeit to a lesser extent (average contribution of -0.4 pp over 2011-2018), partly offsetting the positive effects of lower unemployment.

Nonetheless, these cyclical factors do not explain the weakness in Japan's long-term wage growth relative to other advanced countries (from 1985 to 2018: +0.7% in Japan, +3.5% in the United States and +3.3% in the United Kingdom).

The sharp rise in non-regular work has curbed wages

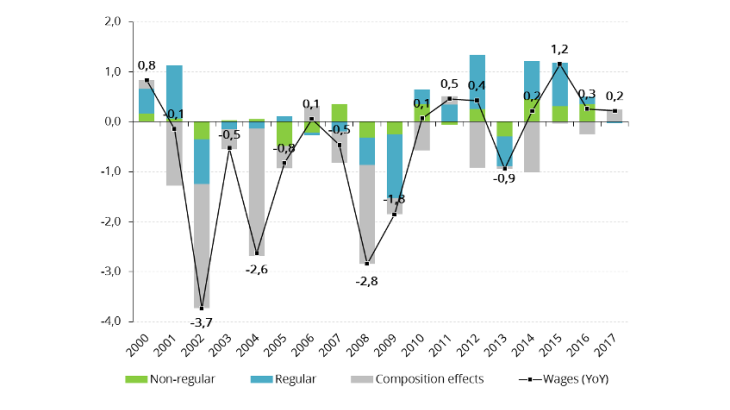

Historically, Japan's social model has always been based on "jobs for life" and steady career progression based on seniority. This model has gradually been replaced by a two-speed system: on the one hand, regular employees who continue to enjoy these traditional benefits; on the other, insecure, non-regular employees (fixed-term contracts, part-time and temporary workers) who are less well paid (34% less on average), and account for a rising share of total employment (38% in 2017 compared with 20% in 1994).

This shift in the structure of employment towards non-regular and lower-paid jobs has had a negative mechanical impact on average wages. Since 2000, composition effects have weighed by an average of -0.7 pp on aggregate wage growth (see Chart 3), although the impact has been less pronounced since 2009 (average contribution of -0.3 pp since 2009 compared with -1.0 pp over 2000-2008).

Japan's social model is also curtailing wage growth

Japan's traditional social model, based on "jobs for life", means that horizontal mobility among employees is low, which in turn lessens the need for employers to adjust wages in order to retain or attract the best workers.

Under this model, the counterpart to job security is that wage flexibility is achieved through overtime and bonuses (which account for an average of 20% of total compensation in Japan compared with 11% in the United States). Companies therefore tend to adapt via this variable portion of pay rather than by raising the basic wage. This phenomenon is detrimental to wage growth not just because a pay rise in one year can be reversed in the next, but also because the variable portion of pay does not apply, or only applies to a limited extent, to non-regular workers.

In addition, Japanese unions have limited bargaining power, despite annual pay negotiations (shunto). Shunto only apply to regular employees at large manufacturing companies, who are declining as a share of the working population as the number of non-regular workers, SMEs and services companies climbs. Aside from shunto, wage bargaining is limited. Unions tend to be specific to individual companies, and therefore lack the national coordination that would give them greater power. They are also facing a decline in membership.

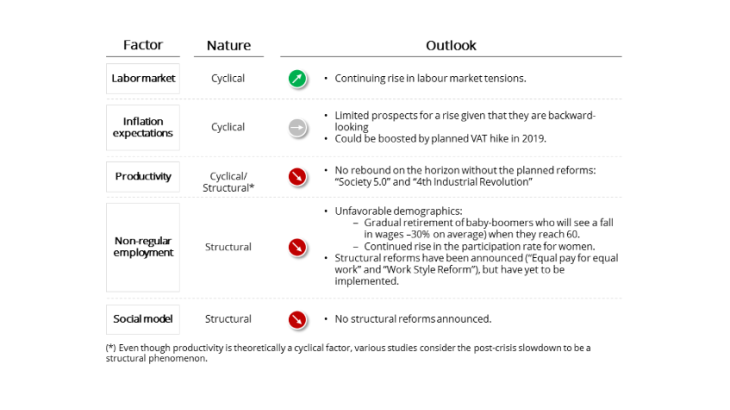

Limited prospects for wage growth without structural reforms

Future wage growth – and therefore inflation – in Japan will depend on the evolution of its individual components (see table). The determinants of the Phillips curve should remain on their current path: unemployment should continue to fall as the labour force shrinks – due to population ageing – while inflation expectations and productivity should remain subdued. Structural reforms would help to improve productivity, but the announced measures ("Society 5.0" and the "4th Industrial Revolution") contain little detail on how they will boost innovation and its diffusion in targeted fields (Big Data, AI, Internet of things, etc.), and should thus only have a limited effect.

Non-regular employment should continue to soar with the rise in the participation rate of women and seniors – categories that both tend to work more in part-time, low-paid jobs. For women, this is due to family obligations and the lack of childcare facilities which make it harder to take up regular positions demanding longer hours - and in particular overtime. Households are also entitled to tax breaks if the 2nd earner's salary is below a certain threshold, creating a low-wage trap. With regard to senior workers, working conditions for the over-60s tend to deteriorate due to a specifically Japanese phenomenon: companies are legally obliged to keep on anyone over 60 who wants to carry on working, but do not have to offer the same terms of contract. In practice, therefore, regular employees receive a large "end-of-career" payoff when they turn 60, then switch to a contract with a lower salary and/or status, sometimes for doing exactly the same job.

Reducing this duality between regular and non-regular workers would require major structural changes. A number of reforms in the pipeline aim to tackle this issue: "Equal pay for equal work" seeks to reduce the pay gap between worker categories, while "Work-style Reform" aims to improve work-life balance by limiting overtime to 60 hours per month. However, it is still not sure when they will be introduced, and implementing them is likely to raise problems, such as how authorities can monitor pay equality in practice.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024