Households do not perceive inflationary pressures any less well than other economic agents: their expectations are generally well correlated with those of professional forecasters (Cœuré 2019) but also with actual inflation (Chart 1). Yet, at the time of the lockdown, households’ inflation expectations and measured inflation diverged in an unprecedented manner. In France, HICP inflation fell sharply, slipping from 1.6% year-on-year in February 2020 to a low level close to 0% in June 2020. At the same time, households were expecting a sharp rise in prices: in April and May 2020, the balance of opinion on inflation expectations in France was between 20 and 25 points above its long-term average. While this balance decreased in June 2020, it remained high relative to the observed inflation level close to 0 (Chart 1). This phenomenon is not specific to France and has been observed across the entire euro area. How can we interpret the specific evolution of households' inflation expectations and their unprecedented divergence from inflation dynamics?

The lockdown suddenly changed households’ consumption basket

The strong and rapid change in the structure of households’ consumption basket during the lockdown may have led to an underestimation of inflation.

Indeed, inflation is measured by statistical institutes as the average annual price variation for a fixed reference basket of goods and services. This reference basket is constructed on the basis of the structure of total household consumption measured in the previous year. The structure of this basket generally varies only slowly from one year to the next, in line with the changes in household consumption patterns. Thus, the fixity of the basket over a year has little effect on the measure of inflation, but it is more problematic when the consumption basket changes suddenly.

Yet, during the lockdown, while overall consumption fell by around 30%, some items of expenditure declined very sharply (transport, accommodation/catering and fuel dropped by between 70 and 90%), while others increased (food) (Insee). All in all, the structure of consumption was thus profoundly altered, which may have affected the inflation observed by households. Indeed, the less consumed goods are those for which prices rose the least rapidly or even fell (fuel, leisure, transport, etc.) while the more consumed goods are those for which prices were the most dynamic (food). According to Insee, taking into account this distortion in the structure of consumption, the annual price increase in France in April 2020 was 1.1 percentage points higher than CPI inflation measured using the pre-Covid 19 fixed consumption basket. Such gap was also observed in many countries: in the United States it is thus estimated at 0.7 pp (Cavallo 2020).

This underestimation of HICP inflation could – partly – explain the divergence between inflation and household expectations. The end of the lockdown has narrowed the gap between households’ actual consumption structure and that of the reference basket of the price index, and thus the difference between published inflation and inflation observed by households from their "lockdown" consumption basket.

Unusual dispersion of price variations and households’ inflation expectations

While households’ average inflation expectations rose sharply during the health crisis, the level of "disagreement" between households is also higher than usual. The proportion of households expecting a sharp price increase over the next 12 months was more than four times higher in France, rising from around the usual 10% to nearly 45%. At the same time, the proportion of households expecting prices to fall doubled. This disagreement has been also observed in the euro area as a whole, and in the United States.

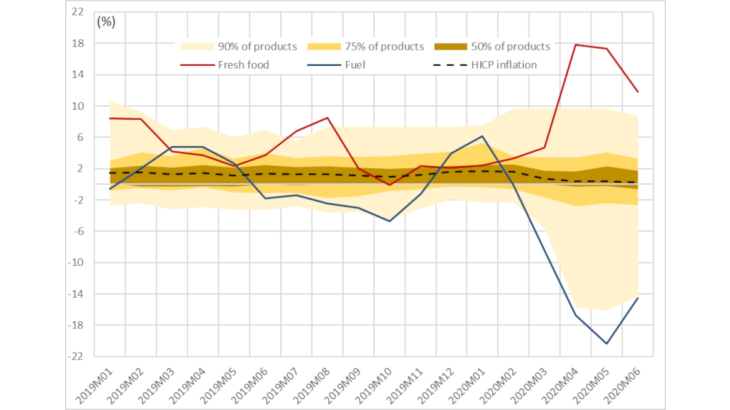

The greater dispersion of households’ inflation expectations mainly reflects the greater dispersion of observed price changes (Chart 2). Although prices have - on average - risen less rapidly than before, there have been more sharp upward and downward movements. Fuel prices fell by 20% year-on-year in April and May 2020, while prices of fresh food have recorded their sharpest increase since January 2002 (climbing by almost 18% year-on-year in April and May 2020).