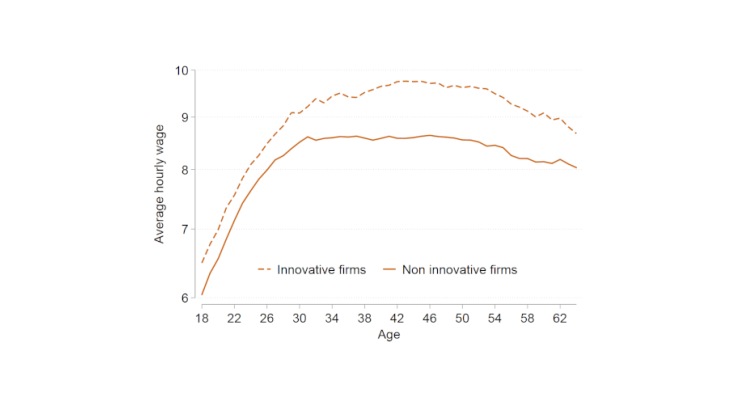

Based on this finding, the study goes on to show that even in a highly advanced technological environment, the most innovative firms still value some low-skilled tasks and therefore pay higher wages than a less innovative firm would for those occupations.

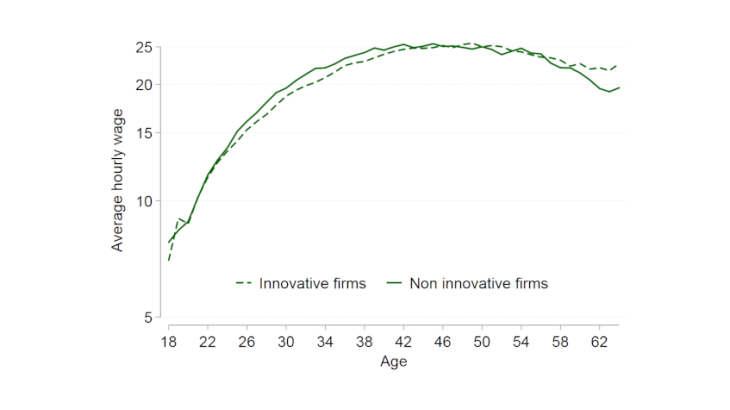

The underlying idea is that all firms value (highly) qualified workers (typically managers, engineers, etc.) on the basis of their technical skills and reputation acquired during their career. To an extent, these characteristics are observable and verifiable, for example by reading a CV. A firm can therefore replace a skilled worker with another worker who theoretically has comparable skills with a relatively small risk of error.

Conversely, the most innovative and technologically advanced firms tend to value more than other firms certain skills of their less qualified employees.

These firms generally have a flatter organisational hierarchy than the average, which translates into increased complementarity between the different workers, particularly between those in low-skilled occupations and those (generally more qualified), who perform more complex and technical tasks. Therefore, in these types of structures, employing individuals who regularly make mistakes is extremely risky. These firms have therefore developed a critical need for the skills of their less qualified workers, such as initiative and reliability. These “soft-skills” are not normally recognised with a qualification and are therefore difficult to observe and, potentially, difficult to replace. More innovative firms are thus willing to pay a wage premium to their employees and to invest more in training their workers. The study shows that, all else being equal, a low-skilled worker employed in an innovative firm earns 24% more than an employee with identical skills and experience but working in a non-innovative firm. Furthermore, on average that same employee will stay twice as long in the firm.

Do these findings contradict skill-biased technological change

How can these findings be compatible with the skill-biased technological change and the widening wage gap based on educational attainment described above? In reality, the phenomenon highlighted in the article by Aghion et al. (2019) only concerns a small number of low-skilled workers, as the most innovative firms have fewer and fewer jobs requiring little or no higher education (these account for only 20% of jobs in the most innovative firms but 64% of jobs in non-innovative firms). In practice, they prefer to outsource the majority of these tasks (particularly security and cleaning) in order to focus their attention and their resources on the few low-skilled occupations that they deem essential to their production process. These are the only occupations that will then benefit from a wage premium.

Ultimately, the most highly skilled workers do indeed benefit most from technological progress, and, unlike the least skilled workers, their labour market power is considerable irrespective of their employer. Nevertheless, these findings demonstrate that even in an increasingly technological environment in which technical abilities are more and more prized, certain skills that do not require a formal qualification continue to be in high demand.