The effect of competition on credit risk is ambivalent

Bank competition has conflicting effects on credit risk, the relative importance of which continues to be the subject of debate. On the one hand, the increase in bank competition leads to an improvement in the quality of credit portfolios. It contributes to improving operational efficiency and the allocation of capital, through the dissemination of best practices and risk analysis methods. These efficiency gains also result in improved data collection by banks and in a reduction of the uncertainty, surrounding borrowers’ default risk, which is particularly high in SSA. Overall, bank competition can contribute, at constant risk-taking, to faster credit development, at a lower cost.

On the other hand, competition between banks may have negative effects on the quality of credit portfolios. It reduces profit margins (or monopoly/oligopoly rents) and encourages banks to take greater risks in order to maintain their ability to generate profits ("franchise value"). These incentives clearly encourage bank lending but may eventually raise the average credit risk of the credit portfolio.

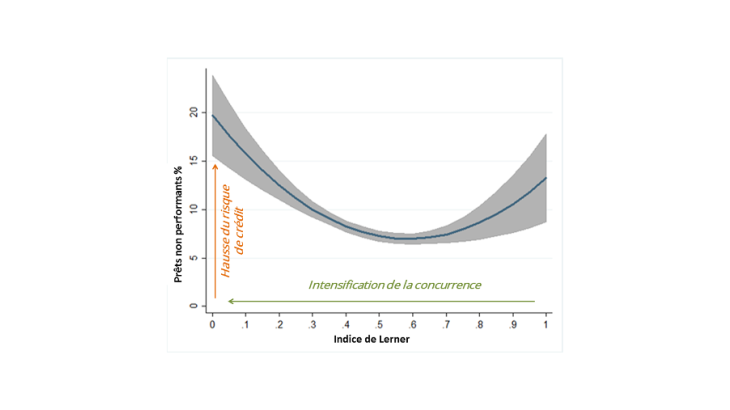

The net effect of these different transmission channels on credit risk depends on the intensity of competition, as well as the macroeconomic, regulatory and prudential environments. According to Brei et al. (2018), the positive effects of increased competition eventually become lower than its negative effects in SSA countries (see Chart 1). This result remains valid even if alternative measures of credit risk (provisions for non-performing loans and distance-to-default - Z-score) and of competition (using a market structure indicator for example) are used.

Strengthening prudential frameworks is crucial to cope with rising risks

Given the potentially negative effect of competition on credit risk above a certain threshold, sustainable credit expansion must go hand in hand with a strengthening of micro-prudential frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa. These frameworks are in the process of being harmonised with international best practices. In 2014, respectively 43% and 40% of SSA countries implemented IFRS accounting standards and Basel II/Basel III prudential frameworks (Guérineau et al., 2016).

The specific risks linked to the financial systems of these countries should also be taken into account, especially given the large share of government securities in bank portfolios in sub-Saharan Africa (20% of the balance sheet in 2015, Fitchconnect). A weighting of sovereign risks is already effective in the franc zone, both in microprudential frameworks and in the bank refinancing mechanisms with the central bank.

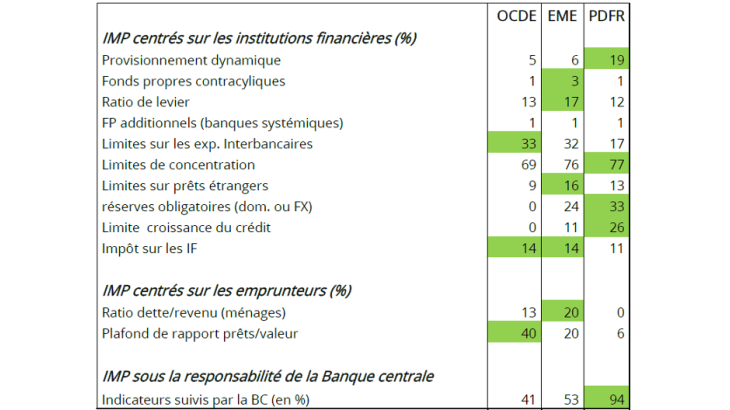

Given that it can result in increased risk-taking and a rise in credit risk, the intensification of competition must also go hand in hand with a gradual strengthening of the macroprudential framework. The objective is to enhance the resilience of banking systems to exogenous shocks and to reduce the pro-cyclicality of bank lending. Again, macroprudential policy instruments may differ from the instruments used in developed countries (see Table 1).

Developing countries, in particular in sub-Saharan Africa, prefer, especially for operational reasons, to use reserve requirements or, in some cases, credit rationing measures (see Table 1). However, assigning macroprudential objectives to such instruments could weaken the monetary policy transmission channels, at least in the countries where these channels are effective or in the process of becoming so. In addition, they may have negative effects in terms of depth and even financial inclusion. Conversely, having recourse to instruments that target debtors could limit these negative effects. This solution should therefore be looked at more closely.