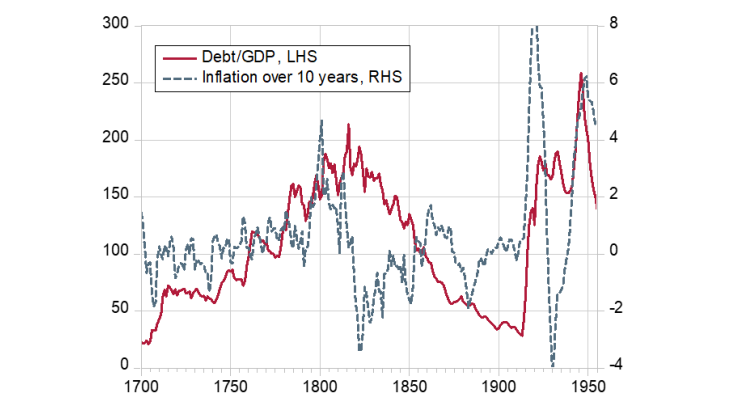

In the public psyche, post-war periods are associated with inflation and even hyperinflation. As wars result in higher public debt, it is common to associate debt with inflation. This impression stems from studies of the 20th century wars. But when older cases are considered, this impression changes. The 18th century and Napoleonic wars resulted in debt ratios of over 100% of GDP with little inflation, as was the case in England until 1914 (Chart 1).

Increases in government debt are therefore not always inflationary. Why? How have governments reduced their post-war debt since 1715? What can we learn about debt management?

Timing is of the essence and the most complex factor

Wars disrupt market economies: monetary and fiscal policies become dictated by military spending, thus generating excess liquidity among private agents. In the post-war period, economic recovery can be thwarted due to the short-term fiscal dilemma and the "tragedy of the economic horizons".

On the fiscal side, the government has a conflict of objectives in terms by how much to reduce the budget deficit: new civilian spending weighs on the deficit while the government has to start paying down its debt. The choice is tricky because government spending that improves supply (e.g. the rehabilitation of mines or the transport network in France after 1918 or 1945) reduces bottlenecks and speeds up the recovery.

Governments face a "tragedy of horizon" between short-term support to GDP growth prospects in the short run and a reduction of the debt burden in the long-term. Fiscal consolidation would restore trust in the government’s creditworthiness and thus limit debt crises. But it would depress growth by limiting government spending on activities essential to the recovery and thus undermine the creation of the resources needed to repay the debt.

In this respect, not all post-war periods have been equal. Without a solution to the tragedy of the economic horizons, inflation would accelerate, with all players protecting themselves from an unsustainable fiscal trajectory. Without a solution to the fiscal dilemma, growth would be weak, amplifying the fiscal difficulties.

Inflation and the post-1918 fiscal dilemma

In the wake of 1918, it proved impossible to reconcile these constraints. The scale of national debt pushed governments to the edge of a cliff. Disagreements over fiscal policy and capital taxation led to capital flight and debt or foreign exchange crises. Inflation rose with every fiscal or foreign exchange crisis as well as due to increased demand. It undermined trust in the government’s creditworthiness as it reduced real fiscal resources while the debt was partly denominated in gold.

A vicious circle sometimes set in: debt crises have hampered recovery, amplifying repayment problems. In Germany and Austria, the monetary financing of government and private spending degenerated into hyperinflation and led to a formal default.

Debt reduction mechanisms

Between 1815 and 1914 and again after 1945, many countries overcame the fiscal dilemma and the tragedy of economic horizons by staggering debt repayments and avoiding restrictive fiscal measures. This was achieved by transferring part of the debt either to commercial banks after 1945 - through financial repression - or to dedicated organisations before 1914.

After 1815, the debt was repaid without default and without significant inflation - or even with deflation in the United Kingdom – as the gold standard was a commitment to return to a balanced budget. In the United Kingdom the debt fell from 213% of GDP in 1815 to 154% in 1825 (Chart 1). Population growth - which increased by a factor of 2.4 between 1815 and 1913 - reduced the debt to GDP ratio by 125 percentage points.

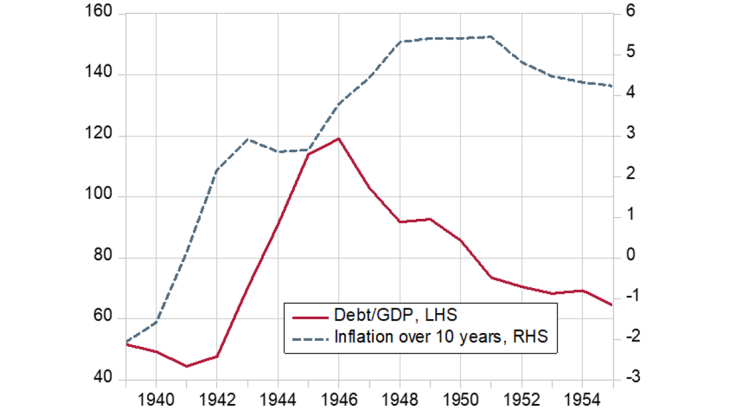

After 1945, inflation reduced the real debt burden. In the United States, government debt was brought down by one-third between 1946 and 1952 by keeping interest rates low during periods of moderate inflation (Chart 2). The Treasury-Fed Accord of 4 March 1951 limited debt montetisation. Overall, between 1945 and 1974, government debt fell by 83 percentage points of GDP, with 20% attributable to negative real interest rates and 40% to either growth or the budget surplus.