- Home

- Publications and statistics

- Publications

- Green premium: can firms fund their gree...

This post is part, with the post 380 “Do green sovereign bonds benefit from a green premium? » (with link) and post 381 “Valuation of the climate risk of corporate bonds” (with link) of the series dedicated to “Green Premiums”.

To finance an environmentally-friendly project, firms can opt to issue green bonds. This study finds that investors are willing to accept slightly lower yields on green bonds. However, this premium (or “greenium”) fluctuates over time, and varies according to euro area country, sector and the green label obtained.

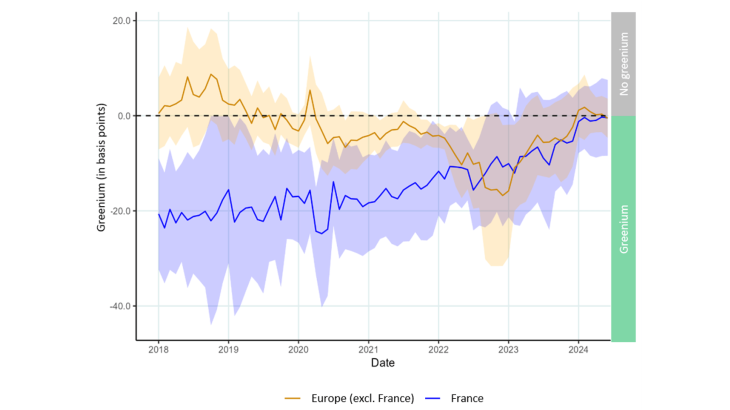

Chart 1: On average, French and European firms benefit from a premium when they issue green bonds

Notes: Change in the premium on green bonds between 2018 and 2024. The greenium (curves) and 95% confidence intervals (shaded areas) are estimated using an econometric analysis.

Green bonds: an instrument for financing the ecological transition

According to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2022), the amount of investment needed to meet the Paris Agreement target of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels must triple by 2030. Green finance can help to meet this need by channelling financial flows towards investments in the ecological transition.

Green bonds were one of the first green financial instruments to be introduced (ABC de l’économie, 2022). They allow public entities or firms to raise funds for projects or activities that benefit the environment. Unlike conventional bonds, they are supposed to provide investors with a guarantee as to the use of the proceeds. Provided they are governed by standards that limit the risk of greenwashing, they can therefore meet investors’ preferences for environmentally-friendly assets.

This blog post analyses the pricing of French and European green bonds in the secondary market compared with that of other comparable bonds. Are investors willing to accept lower yields to finance firms’ ecological transition? Our analysis relies on a database on debt securities issued by financial and non-financial corporations listed on an organised euro area market. The greenium is estimated via an econometric analysis (a panel regression), which measures the yield spread between green bonds and comparable conventional bonds, after controlling for the effect of a set of issuer and bond characteristics. The methodology is inspired by various academic studies on the topic (e.g. Tang and Zhang, 2020).

There are several arguments in favour of a greenium

As with other financial instruments, the price of green bonds is set according to supply and demand. An imbalance between supply and demand can lead to a shortage of green bonds, resulting in the emergence of a greenium.

On the supply side, green bonds cost more to issue than conventional bonds. There are greater transparency requirements regarding the use of proceeds, as issuers have to commit to invest in specific green projects. In theory, this cost could limit the supply of green bonds, unless they offer issuers other benefits – a means of signalling their commitment to the environment, or a financial advantage whereby investors are prepared to accept a discount relative to conventional bonds, in other words a lower yield (a greenium). This discount can offset the additional cost of issuing a green bond and potentially lower the cost of financing (Flammer, 2021).

On the demand side, some investors have a preference for green bonds because of the associated environmental commitments (Pedersen, Fitzgibbons and Pomorski, 2021). Demand for green financial instruments is therefore rising rapidly, fuelled by growing investor interest in extra-financial considerations, and especially environmental criteria (Fama and French, 2007). Government tax incentives may also play a role in expanding the market for green bonds (Agliardi and Agliardi, 2019).

The greenium is significant overall, but relatively unstable

Our analysis finds that the average greenium for French issuers remained firmly negative between 2018 and 2023, indicating that investors accepted a lower yield on green bonds than on conventional bonds (see Chart 1). The greenium reached a record level in June 2020, before gradually shrinking between 2021 and 2023, and then disappearing altogether in 2024. However, over the period, the greenium was statistically significant in average terms, including when comparing green and conventional bonds issued by the same issuer, and taking account of various other factors influencing bond risk and returns (amount issued, residual maturity, coupon and liquidity). This suggests the existence of a possible imbalance, with demand exceeding supply, and then the disappearance of this imbalance at the end of the period.

The average greenium for European issuers was smaller over the period and fluctuated more markedly. It only turned negative after the public health crisis in 2020, varying between 2 basis points and -17 basis points. This trend may reflect increased demand for green bonds from retail investors (Pietsch and Salakhova, 2022).The premium increased sharply in 2022 due to a fall in green bond issues (Caramichael and Rapp, 2022), before declining in 2023 and then disappearing altogether in 2024.

These results are partially similar to those of two other blog posts published alongside this one: Descombes and Szczerbowicz (2024) find that euro area sovereign green bonds issued between 2021 and 2024 benefited from a greenium, while Clémentin and Serge (2024), find fluctuations in the premium on conventional bonds issued by green issuers, followed by its disappearance and the emergence of a brown premium at the end of the period.

The greenium varies according to euro area country, sector and type of label

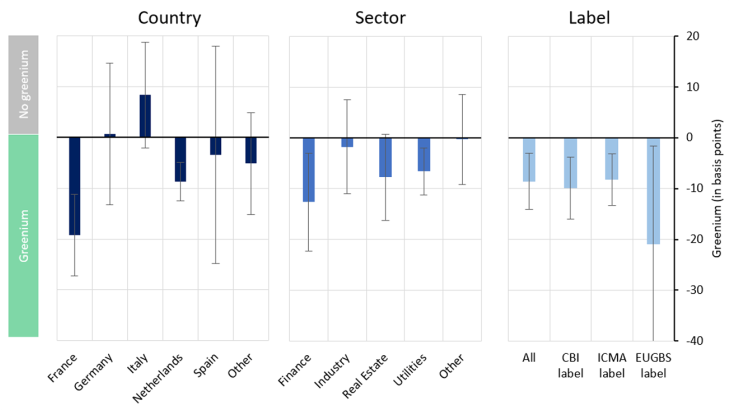

In Europe, only French and Dutch issuers appear to benefit from a significant greenium (see Chart 2). For other euro area issuers, no significant yield spread is found between green bonds and comparable conventional bonds. In Germany and Italy, the yield on green bonds is in fact higher than that on conventional bonds (but not significantly so), contrasting with the findings of Descombes and Szczerbowicz (2024) for German and Italian sovereign bonds.

The greenium also varies from sector to sector. It is large for financial corporations, who are the main issuers of green bonds. It is also significant for public utilities (electricity, gas and water companies, etc.) and real estate firms. In contrast, firms in other sectors, notably industry, which issue fewer green bonds, do not benefit from a greenium.

These variations in the greenium could also be due to the lack of binding regulations on green bonds, which can raise suspicions of greenwashing among investors. Although a set of good practices has been defined to frame these instruments and establish environmental criteria for eligible projects, none of these are mandatory, and there are divergences between the main market standards (International Capital Market Association – ICMA, Climate Bonds Initiative – CBI, etc.). In response, the European Union has established rules with stricter requirements for transparency and external review (European Green Bond Standard – EUGBS). The EUGBS standards were adopted on November 2023 and will be applied from December 2024. While ICMA and CBI-certified green bonds trade at close to the average greenium for all green bonds, bonds seeking EUGBS compliance – or already partially compliant – of which there are far fewer, trade at a higher premium. This suggests that investors are sensitive to information quality.

If the existence of a greenium in the secondary market also implies a discount at issuance, green bonds could offer firms a cheaper way of financing their investments in the ecological transition, provided they are combined with a high-quality labelling system and used to fund relevant projects.

Chart 2: The greenium varies across European countries and sectors, and according to the label obtained

Notes: Premium on green bonds between 2014 and 2023. The greenium (bar chart) and 95% confidence intervals (grey lines) are estimated using an econometric analysis

Download the full publication

Updated on the 3rd of January 2025