This paper stresses that fixing the exchange rate can have positive effects on the economy, as it helps to reduce inflation and its volatility persistently. We spell out conditions under which fixing the exchange rate does have effects and when it does not. We also provide evidence for the quantitative magnitude of lower inflation when pegging and which countries in particular can benefit from such a regime shift.

In essence, we highlight and quantify the ``credibility channel'' in which a central bank gains credibility when committing to peg the exchange rate. Countries with non-credible central banks suffer an inflationary bias that has its origins in discretionary monetary policy. This means that time-inconsistent monetary policy is tempted to react to economic shocks with an inflationary monetary stance. We provide a theory in which some countries are able to diversify away these “temptation shocks” more efficiently than others, resulting in more credible institutions, less discretion, and lower inflation rates. We derive several testable implications in an estimated quantitative model when a country with time-inconsistent monetary policy pegs to a more credible anchor: First, inflation and its volatility should go down permanently. Furthermore, real GDP growth goes up in the short-run as the costs of high inflation go down. Last, we emphasize that those effects are stronger the less credible the pegging country is. Using this model, we provide an estimate of credibility for 170 countries between 1950 and 2019.

We also discuss the conditions of a successful peg and how low credibility countries can maintain a fixed exchange rate. If the peg can collapse at any point in time, the gains of lower inflation disappear as firms, markets and households anticipate the dissolution. We show that a dissolution becomes much less likely if there are break-up costs of a peg. A central bank would nevertheless opt for a peg with potential break-up costs if the gains from lower inflation are ex ante high enough. Other factors that are important for a peg, such as structural reforms or foreign reserves are not considered and left for future research.

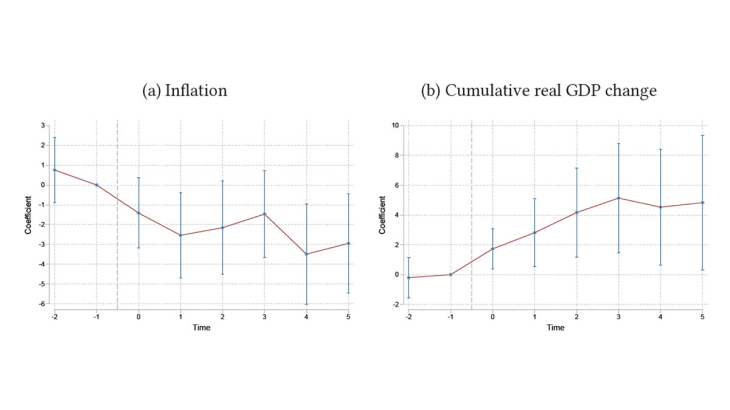

In our empirical analysis, we use the most comprehensive dataset available at the country level, with information on 170 economies over the last 70 years, corresponding to approximately 8,000 country-year observations including 282 pegging episodes. These episodes include the pegs that preluded the formation of the Euro area. We start by documenting that our proposed measure of a country's credibility is aligned with other measures of central bank independence, inflation expectations' anchoring, and central bank governors' average tenure. We then emphasize 3 stylized facts on the differences between countries in float and fixed exchange rate regimes: 1) inflation is higher and more volatile in floats than in pegs; 2) real GDP growth is higher in pegs; 3) interest rates are higher and more volatile in floats than in pegs. In addition, we also perform an event study analysis around changes in exchange rate regimes and confirm that following a pegging episode countries display lower inflation and interest rates and higher economic growth, as indicated by regression results in Figure 1. These empirical findings provide support for the implications of the model: When a country pegs its currency, both inflation and its volatility decrease while real GDP increases. The less credibility a country has, the larger these effects are.

Keywords: Exchange Rate Regimes, Monetary Policy, Interest Rates, Inflation

JEL classification: E31, E42, E52, F41, F42