- Home

- Publications and statistics

- Publications

- The four seasons of the financial cycle ...

The four seasons of the financial cycle and the countercyclical capital buffer

Post n°75. Financial cycles can be broken down into four phases in which the intensity of financial risks changes. The crisis that follows the downturn is all the more pronounced as risks have accumulated during the upturn. Macroprudential policy aims to limit the impact of financial crises on the real economy: the decision to activate the countercyclical capital buffer in France meets this imperative.

What is financial cycle ?

Analysing financial cycles enables us to better understand, anticipate and prevent the consequences of their turnaround. However, there is no clear and commonly accepted definition of the financial cycle. According to Borio (2014), the financial cycle refers to "self-reinforcing interactions between perceptions of value and risk, attitudes towards risk and financing constraints, which translate into booms followed by busts". In other words, when all goes well, economic players who are collectively optimistic (but potentially short-sighted) may take greater risks that could lead to the formation of financial imbalances. Conversely, during a downturn, previously accumulated imbalances are resolved, sometimes quite suddenly, which leads banks (investors) to restrict their supply of credit (financing), thus accentuating the amplitude and length of the following recession phases. Schematically, the financial cycle can be divided into four phases.

- Spring is the upswing in the cycle when economic prospects improve: confidence returns which fosters lending and investment, financial constraints are eased, debt rises and asset prices increase; at the same time, risks pick up but remain under control.

- Summer (or even heatwave) is the phase of overheating during which excess confidence and an underestimation of risks lead to asset price bubbles and runaway debt due to the easing of financial constraints. In addition, the correlations between market segments or countries rises, as reflected in the synchronisation of asset price increases and risks.

- Autumn is characterised by the turnaround in the cycle: confidence vanishes (often as a result of the first negative events caused by excessive risk-taking in the summer), leading to a sudden tightening of financial constraints, an increase in counterparty risk, a fall in asset prices and a reduction in debt. The economy is plunged into a financial winter during which the summer imbalances are resolved.

- Lastly, winter is the phase where the vulnerability of financial system players, the depressed economic outlook and strong financial constraints fuel a recessionary climate during which the financing of the economy is constrained. It is followed by a long and costly period of adjustment during which imbalances are resolved before a new financial cycle begins

The main difficulty, despite this repetition of the "seasons", is that you never know how long summer will last and yet, invariably, there is a winter: "Winter is coming". There is also the question of the magnitude of each phase, especially winter: the downward phase of the cycle may be smooth but it may also turn into a severe and costly financial crisis. Being able to concretely observe the cycle dynamics over time and establishing the position of a country in the financial cycle is therefore a very delicate exercise but one of paramount importance for implementing a suitable macroprudential policy.

How to statistically measure the financial cycle?

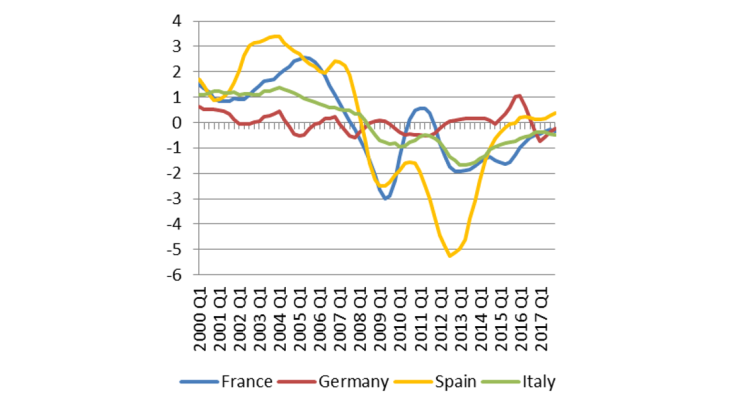

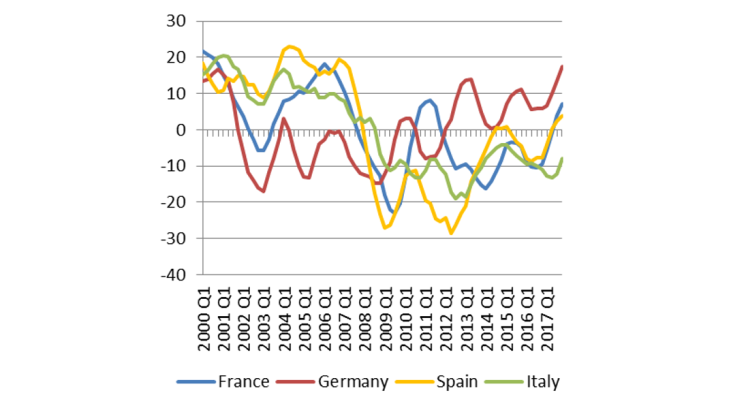

The list of indicators used to capture the financial cycle is not set in stone. Two elements, however, can be found in the vast majority of methodologies: debt and real estate prices (see Merler (2015), Chart 2). Indeed, these two variables have been at the heart of the major financial crises in recent decades (in 2008 in the United States, Ireland and Spain, and in the early 1990s in France and the Nordic countries). Other "revealing" indicators of the financial cycle are increasingly integrated (equity prices, bond prices) to better reflect the diversity of the financial system (see Schuler, Hiebert, Peltonen (2015), Chart 3). Once the list is closed, different statistical methods may be used both to aggregate these indicators and to account for their common dynamics. These measurement uncertainties justify the large variety of methods.

Note: The estimated cycle is obtained from a Principal Component Analysis of the underlying variables; there is therefore no unit or bound. Zero is the historical median.

Note: The estimated cycle is the average of the empirical cumulative distribution functions of the underlying variables, re-based on +/- 50 (all components are at their historical high/low). Zero is the historical median.

The two models illustrated in Charts 2 and 3 show that after 2008, the financial cycle based solely on real estate prices and the dynamics of non-financial private sector debt displays a smaller amplitude due to a depressed real estate market in many countries. The cycle based on more diversified indicators, notably equity and bond markets, is more dynamic, in particular in the recent period for France, Germany and Spain.

Getting ready for the turnaround in the financial cycle : the purpose of the countercyclical capital buffer

The countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) is a capital surcharge for banks. In France, it is set by the macroprudential authority, the Haut Conseil de Stabilité Financière (HCSF - High Council for Financial Stability) (see implementation Note), under the chairmanship of the Minister of the Economy and Finance and on the proposal of the Governor of the Banque de France. Thanks to this buffer, the capital accumulated preventively in spring and summer of the financial cycle may be used in autumn, thus limiting the harshness of winter.

Once set up, the countercyclical buffer may be instantly deactivated by the HCSF during the economic downturn: banks are then less constrained to restrict the supply of credit (in particular to restore the soundness of their balance sheet) and this contributes to the financing of the economy. The winter depression is then weaker and shorter.

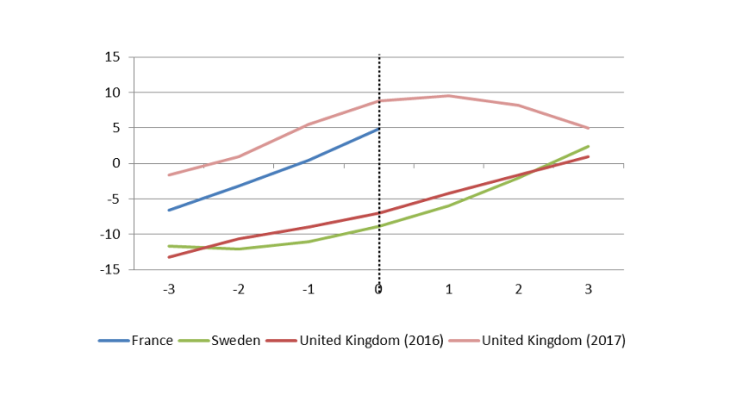

Sweden (in late 2014) and the United Kingdom were the first countries to activate this buffer. The United Kingdom has activated it twice, in 2016 and 2017, after deactivating it at the time of Brexit. In the euro area, France is, since 1 July 2018, the first major country to have decided to activate this instrument (see the Decision and the Press Release). Each time, this activation took place during the upswing of the financial cycle (Chart 4).

Note: Schuler-type model (2015). On the x-axis, the number of quarters before (-) or after (+) the activation of the CCyB standardised at t = 0. The chart takes into account the information available to decision-makers at the time of activation.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024