Analyses of inequality typically provide snapshots at a given point in time, without considering the trajectories of individual earnings over their lifecycle (“Lifetime earnings” or LTE). Assessing how the well-documented gender differences in annual earnings translate into the gender gap in lifetime earnings remains an open question. Several factors that have a different impact on the annual earnings of men and women over their life cycle are likely to affect their lifetime earnings too, e.g. differences between men and women in participation rates, hours worked, unemployment rates or average hourly earnings.

To address this issue, Garbinti et al. (2023) compute lifetime earnings based on the Permanent Demographic Sample for France (EDP) produced by the National Statistical Institute (Insee). This large socio-demographic panel includes administrative payroll data from firms, providing information on employee earnings over the period 1967-2017. In order to mitigate possible sample bias, the sample is selected so as to focus on individuals displaying sufficient attachment to the labor market (i.e. individual earning at least a sixteenth of the minimum wage in at least half the period between ages 25 and 55) and who are still alive at age 55. For each individual, lifetime earnings are defined as the average of annual earnings between ages 25 and 55. This 31-year period, the ‘lifetime’, is available for those born between 1942 and 1962, with the youngest cohort reaching age 55 in 2017. Throughout this analysis, a cohort is identified by the year in which they turned 25. The methodological setting follows Guvenen et al. (2022) Guvenen et al. (2022) in order to provide meaningful comparisons between the French and US cases. This comparison is particularly interesting as France is, relative to the US, a country characterized both by a lower level of cross-sectional inequality (e.g. Alvaredo et al. (2018), Garbinti et al. (2018))and limited income mobility (Aghion et al. (2023), Kramarz et al. (2022)).

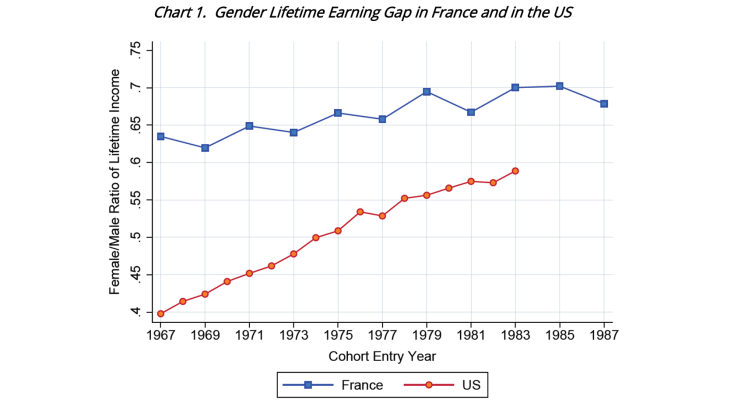

The lifetime gender gap has narrowed across cohorts (Chart 1), both in France and in the US. For instance, in France, women's earnings averaged over ages 25-55 peaked at 70% of those of men for the 1983 and 1985 cohorts. This ratio increased from about 61% to 70% over the 1967 to 1983 cohorts, while in the US it soared from about 41% to 60% over the same cohorts. This narrowing of the gender pay gap in the United States has been studied in detail by Claudia Goldin, the 2023 Nobel laureate (see, for example, Goldin (2014)).

As a result, women’s lifetime earnings as a percentage of men’s are far larger in France than in the US for all cohorts. Moreover, the narrowing of the gender gap results from very different gender dynamics in the two countries.

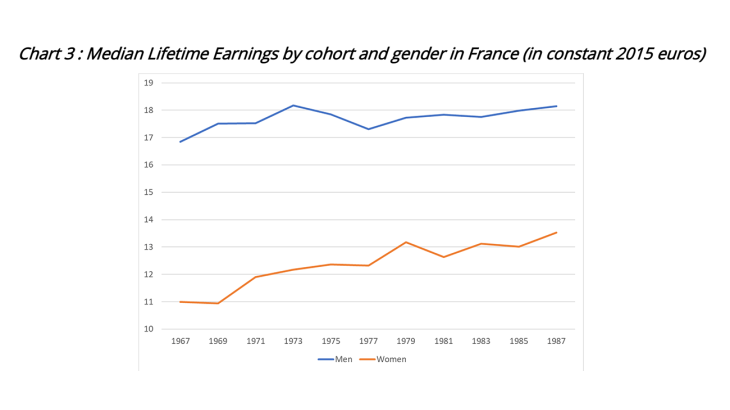

Contrary to the US, trends do not strongly differ for men and women in France

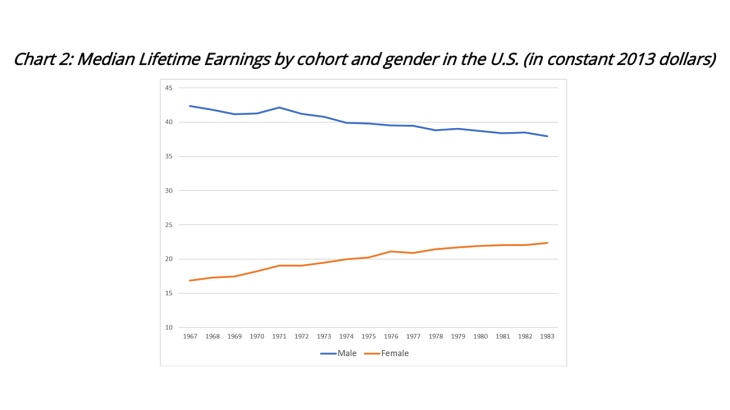

In the US, the narrowing of the gender gap reflects heterogeneous trends across genders. Chart 2 shows the dynamics of LTE for the US, displaying considerable losses for men (-10%) and large gains for women (+33%) (Guvenen et al., 2022). These different dynamics have led to the sharp reduction in the gender gap observed in Chart 1.