IMF Annual report on exchange rate arrangements and exchange restrictions, August 2021, for the definition and classification of exchange rate regimes, flexible exchange rate regimes include managed flexible systems.

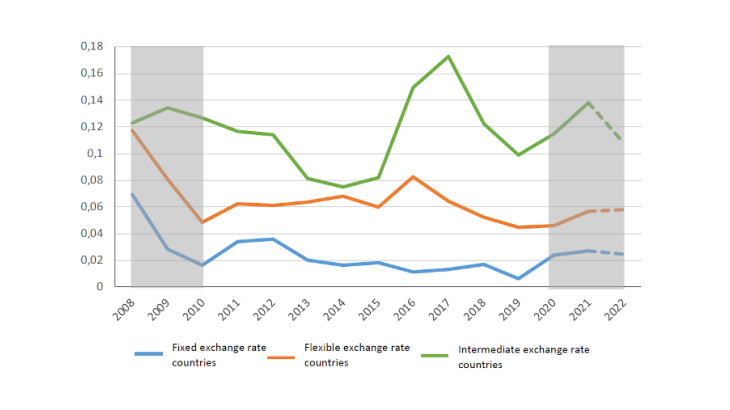

Note: GDP-weighted averages at current prices. Ethiopia is excluded from the sample (intermediate exchange rate regime) as forecasts are not available.

How has monetary policy space changed with the Covid-19 crisis?

The objective of most central banks in SSA is to ensure the stability of their currency. Even in inflation-targeting countries, this stability is considered as both external (nominal exchange rate) and internal (inflation), with the external anchor still necessary because the internal anchor is not sufficiently effective. The more stable the exchange rate and the more inflation is under control, the more space the central bank has for a counter-cyclical response, and vice versa.

Even if this observation cannot be extended to all SSA countries, the current crisis has, to date, had less of an impact on external stability than the 2008-2009 crisis, thanks to financing conditions on international markets that have been favourable once again since autumn 2020 and thanks to international financial support. This stability is often analysed in terms of two indicators, as the IMF does, for example, in its Regional Economic Outlook for Africa (REO) of October 2021: the evolution of the level of foreign exchange reserves and the exchange rate. On this basis, compared to countries with flexible or intermediate exchange rates, countries with fixed exchange rates have been better shielded from exchange rate pressures in the current crisis, and at no cost to their growth performance. This is particularly true for the countries of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) and, to a lesser extent, for the countries of the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CAEMC)). According to the IMF, these two monetary unions, whose currencies are pegged to the euro, posted average GDP growth rates of +4.4% and +0.3% in 2020 and 2021, compared with, respectively, +3.1% and -1.7% for the whole of SSA.

In terms of inflation, the observation is also clear, particularly in view of the situation observed in 2021 and early 2022 (see chart above). The current crisis has led to a sharp rise in inflation in SSA (10.7% annual average in 2021, compared with 8.2% in 2019, IMF REO October 2021), in contrast to the previous crisis, which saw inflation fall from 11.7% in 2008 to 7.5% in 2010, IMF REO April 2011 (see chart). The current rise in inflation is leading to a sharp reduction in policy space of some central banks, particularly for countries without fixed exchange rate regimes. According to the IMF (REO October 2021), inflation should rise to 2.1% in CEMAC and 2.9% in UEMOA in 2021, compared with 24.4% in Angola, 22.8% in Zambia and 16.9% in Nigeria, to take a few cases of countries with an intermediate exchange rate regime.

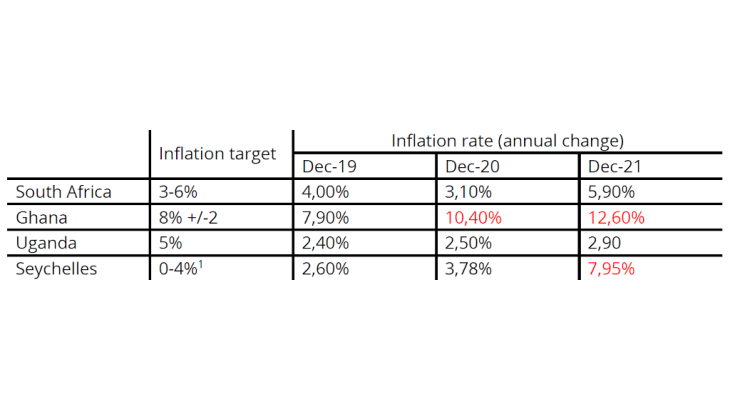

Moreover, it is important to specify that this reduction in policy space is not linear, but tends to accelerate beyond certain thresholds. Indeed, when monetary stability (external or internal) is established, the credibility of the central bank is not called into question, but it may be when the situation is far removed from equilibrium. For the exchange rate, this generally means a fall of over 25% over a short period (Frankel and Rose (1996), p. 353) or a level of foreign exchange reserves of less than three months of imports of goods and services (the so-called Greenspan-Guidotti rule (Jeanne and Rancière (2006), p.6)), standards frequently used by the IMF. In terms of inflation, levels well above the central bank's target are likely to trigger "snowball" effects that could lead to an unanchoring of inflation expectations. According to the IMF (Annual Report on Exchange Rate Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions), two of the four SSA countries that have adopted an inflation targeting regime, Ghana and Seychelles, could be in this situation (see Table).