After peaking at over 10% between 2012 and 2016, the French unemployment rate has been falling almost continuously since 2016, reaching a historic low of 7.1% at the end of 2022, and standing at 7.3% in Q2 2024. While this fall is partly due to cyclical factors - the Banque de France forecasts a slight temporary rise in unemployment to 7.6% in 2025 - it is primarily the result of structural factors that can be understood by analysing the movements of workers between employment and unemployment. Leaving aside the increase in the participation rate [measured by the ratio (employment + unemployment)/working-age population], which has not directly contributed to the change in the unemployment rate since 2015, the change in unemployment is a function of two factors: the number of unemployed people who find a job on the one hand, and the number of ‘newly-unemployed people’ who have lost their jobs on the other. In practice, these flows are expressed in terms of the rate at which the unemployed return to work, and the rate at which people leave employment and become unemployed. These rates are calculated using the Shimer method (2012), which uses the equilibrium relationship that exists between the levels of total unemployment and short-term unemployment. The rate of return to employment measures the proportion of unemployed people who find a job. The rate of exit from employment measures the proportion of workers who become unemployed. At any point in time, the unemployment rate reflects these two opposing flows. This post aims first to analyse the influence of fluctuations in these rates on the actual unemployment rate, and then to explore the underlying forces that drive these variations.

Changes in the rate of return to employment account for most of the recent fall in unemployment

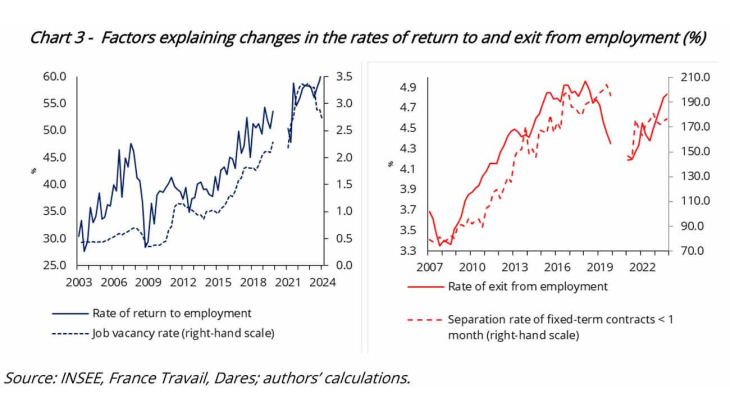

Chart 1 shows changes in unemployment-to-employment and employment-to-unemployment flows between 2003 and 2023. These flows are calculated using the Shimer method (2012), which measures changes in the rate of return to employment based on changes in the share of short-term unemployment, assuming a constant participation rate. We observe that, despite fluctuations, the rate of return to employment has generally trended upwards since 2015, indicating a gradual improvement in unemployed people's chances of finding a job again. At the same time, the rate of exit from employment rose significantly after the economic crisis from 2009 on, peaking in 2015 before levelling off. After plunging during the Covid-19 pandemic, it now seems to be gradually returning to its pre-crisis level.

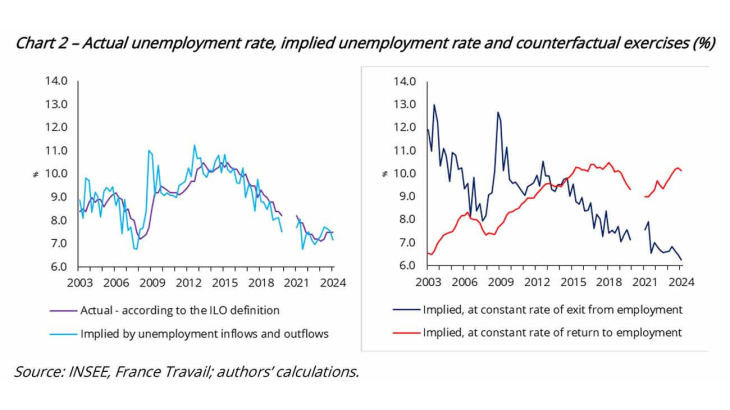

As Chart 2 shows in the left-hand panel, the unemployment rate implied by flows into and out of the labour market faithfully reproduces the actual dynamics noted in the unemployment rate, while exhibiting slightly higher volatility. This confirms the relevance of unemployment inflows and outflows in understanding the actual level of unemployment, despite the strong assumption concerning the participation rate. Indeed, the participation rate has increased by around 3 percentage points over the period under consideration, due to the increased participation of women and workers aged between 50 and 64 (as a result of the gradual increase in the retirement age). However, this increase is very gradual and is driven by people moving directly between inactivity and employment, which means that the flows between unemployment and employment account for most of the changes in the unemployment rate over the cycle. 2020 is excluded from our analysis because of the public policy choices made during the Covid-19 pandemic, which temporarily froze the labour market, leading to an artificial fall in exit and return-to-work rates, unlike what happened in the United States, for example.

The right-hand panel of Chart 2 reproduces Shimer's (2012) counterfactual exercise, which consists in simulating what the observed unemployment rate would have been if either of the two flows had been fixed at their average over the entire period under consideration. The idea is to highlight the significance of fluctuations in the rate of return to employment and in the rate of exit from employment, for fluctuations in unemployment. Therefore, the blue curve represents the implied unemployment rates when only fluctuations in the rate of return to employment are considered, while the red curve represents the implied unemployment rates when only changes in the rate of exit from employment are considered. We note that it is the blue curve that best reflects the overall dynamics of unemployment over the period in question. More specifically, this exercise shows that most of the variation in the unemployment rate (82%) is attributable to fluctuations in the rate of return to employment, while the remainder is accounted for by fluctuations in the rate of exit from employment. This result for France is consistent with Shimer's findings for the United States. We also note that the fall in unemployment that began in 2015 is entirely attributable to the increase in the rate of return to employment over the period.