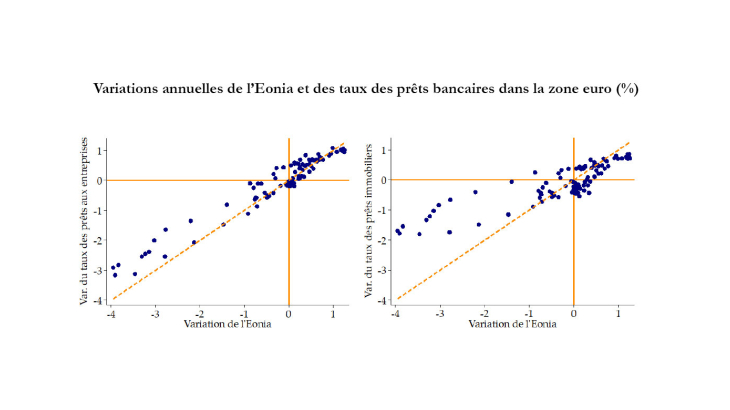

Standard practice in structural macroeconomic modelling is to assume that retail bank interest rates adjust similarly upward and downward following economic shocks. However, empirical evidence from banking data suggests that bank lending rates (BLRs) are downward rigid. As shown by the Figure below, banks tend to adjust their rates slowly and incompletely in response to monetary policy easing, while they do increase them fairly quickly and rather proportionally as policy rates increase.

What are the macroeconomic effects of such a downward interest rate rigidity? What are the consequences of neglecting it in standard macroeconomic modelling?

In this paper, we address this question by introducing asymmetric bank lending rate adjustment costs in a macrofinance dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model. The model is calibrated on euro-area data, by matching in particular the empirical (low) volatility and (significantly positive) skewness of year-on-year changes in business and mortgage lending rates.

We propose a comparison of the effects of several structural shocks on the real economy in the presence of such an interest rate asymmetry. We find that the difference in the initial response of GDP to positive and negative shocks of similar amplitude can reach up to 25%. This implies that a central bank would have to cut its policy rate much more to obtain a medium-run impact on GDP that would be symmetric to the impact of a shock implying a policy rate increase. This refers to the famous "string" metaphor: employing tight monetary policy to curb excess demand and inflation is like pulling on a string – it works well. However, attempting to stimulate the economy with loose policy during a downturn is like pushing on a string – it is not very effective. In this vein, we examine the effort that the central bank could make to compensate for the downward rigidity of BLRs. We find that a central bank would have to decrease its policy rate by 20% to 100% more to yield a medium-run impact on GDP that is symmetric to the impact of a positive monetary shock.

Finally, by investigating the post-2012 period, we show that downward interest rate rigidity is even stronger when policy rates are stuck at their effective lower bound. This is mainly due to the existence of a lower bound on deposit rates, but also to a lower bound on BLRs stemming from frictions that are intrinsically related to banks’ business model. In Europe, a weaker intermediation margin could hardly be compensated by other sources of profitability because of overcapacity (low cost-efficiency) and insufficiently diversified structure of revenues (weak income-generation capacity). Hence, deterioration in profitability may induce a lower bound on BLRs, which reduces the effectiveness of monetary policy. This deterioration of the pass-through of monetary policy in periods of ultra-low interest rates justifies a strong reaction to negative shocks. For example, this supports the large-scale unconventional measures implemented by central banks in 2020 to counteract the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

More generally, given its macroeconomic consequences, neglecting downward interest rate rigidity in macroeconomic models may yield misguided monetary policy decisions.