The NIIP results from two factors: financial effects and real factors

The NIIP represents the net balance of claims and liabilities vis-à-vis non-residents. The NIIPs of G20 countries have diverged since 1990: from a situation of near-equilibrium for all countries, they have become polarised and have shown strong liability or asset positions depending on the country.

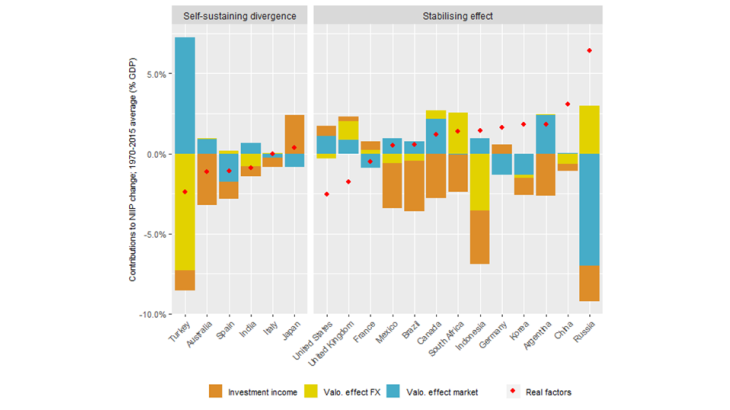

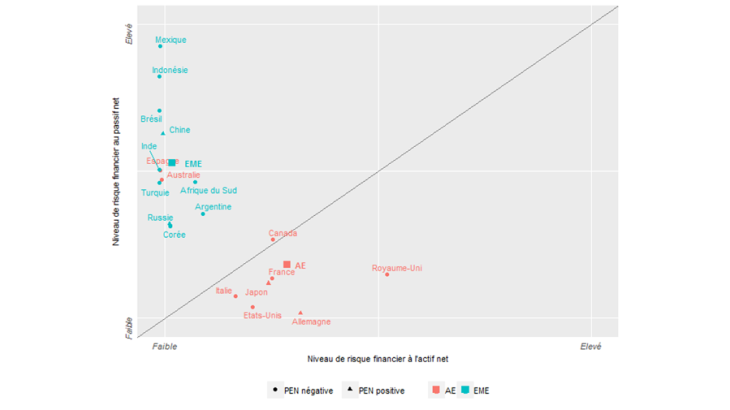

In accounting terms, the NIIP of a country results from real determinants (trade balance, labour income, etc.) on the one hand, and from two financial determinants (valuation effects, i.e. capital gains or losses on portfolios related to changes in the price of financial assets or the exchange rate for portfolios denominated in foreign currency, net investment income, i.e. dividends and interest from net assets) on the other. These financial determinants depend solely on the NIIP itself, on its asset structure and on the amount of net assets; they are therefore comparable to a NIIP’s internal dynamics.

It is key for the study of global imbalances to understand the impact of these financial effects, especially as the exacerbation of IIPs has greatly increased their magnitude over the past 30 years. If the impacts of financial effects and real factors have the same sign, the divergence of the NIIP is self-sustaining with a "snowball" effect. A negative (positive) NIIP due to the accumulation of real factors would be impacted by negative (positive) financial effects that would polarise it even more. Such a situation would be a source of concern as it would make resolving global imbalances in G20 countries more difficult.

Financial effects generally have a stabilising effect, linked to the structure of the portfolio

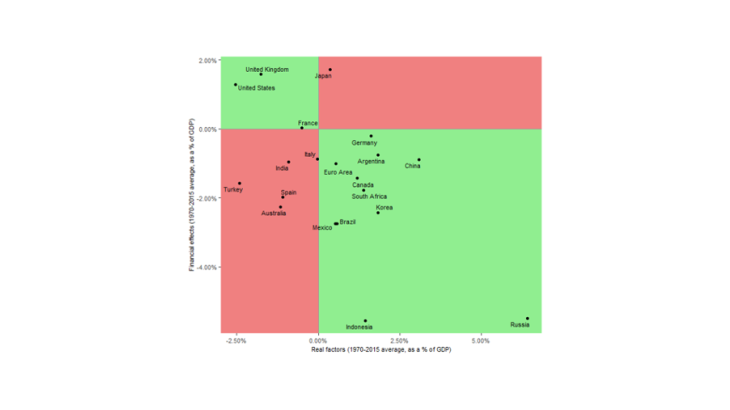

On average, over the period 1970-2015, financial effects had a rather stabilising long-term impact. In most G20 countries (14 in the green areas on Chart 1), they had an opposite sign to that of real factors: the financial dynamics offset the impact of real factors. In other words, the divergence of their NIIPs would have been greater without these financial effects. This was not the case for the countries in the red areas (6) whose financial effects exacerbated the polarisation of their NIIP.

This stabilising effect results from investment income and the market effect (see Chart 2) and concerns mainly two types of countries:

- Deficit advanced countries that issue a reserve currency backed by a global financial centre (United States, United Kingdom). These countries finance their deficits in the form of debt securities and make outward equity investments and FDI: because of the differences in yields between these asset classes, they derive a higher average yield on the assets side than what they pay on the liabilities side. This is heightened by the differences in yields, within the same asset class, with claims being less remunerative than liabilities – e.g. in the United States, a higher yield on outward FDI than on inward FDI, see Bosworth et al. (2007). Financial effects have a positive impact, offsetting the goods and services deficit;

- Surplus emerging countries (Argentina, China, South Africa, Mexico, Brazil, Korea, Indonesia, Russia) which invest in debt securities for a liabilities side composed of equities and FDI. Financial effects, which are negative, offset the persistent surplus on other items.

Conversely, deficit emerging countries (India and Turkey) are faced with a snowball effect: their NIIP, which consists of debt securities on the assets side and equities and FDI on the liabilities side, generates negative income and valuation effects, which exacerbate the effect of the trade deficit.