How do weather-related disasters affect consumer prices? At a time when central banks are considering climate risks in their operational frameworks, this question is becoming relevant for monetary policy. Existing empirical literature has mainly focused on the overall effect on prices, cloaking the complex interplay of supply disruptions following natural disasters that drive up prices in the short run, combined with a shock to the composition of aggregate demand. This paper documents how prices of granular Consumer Price Index (CPI) product categories respond to weather-related natural disasters. The full decomposition across product categories in geographically small regions refines our understanding of the inflation response to extreme weather events. Given that disasters are expected to become more frequent as a result of climate change, our findings help policymakers to address the important challenge posed by uncertain climate change more appropriately.

A challenge for the measurement of causal dynamic effects from weather-related disasters is the imprecise measurement of economic damages resulting from asset impairment and business interruptions following natural disasters, which are not directly observable. We propose an empirical strategy that combines events from two disaster databases and different meteorological records to assess the intensity of economic damage in a first-stage regression, which can account for various country-specific factors that determine the relationship between the intensity of weather events and economic damages at the local level. By doing so, we select economic disasters that we can directly connect to extreme meteorological events. To assess the inflation effects of natural disasters, we then relate the economic disasters as predicted by the first-step equation to the evolution of prices for different time horizons following the shock. We focus our empirical analysis on prices in four French overseas territories, namely Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana and Réunion.

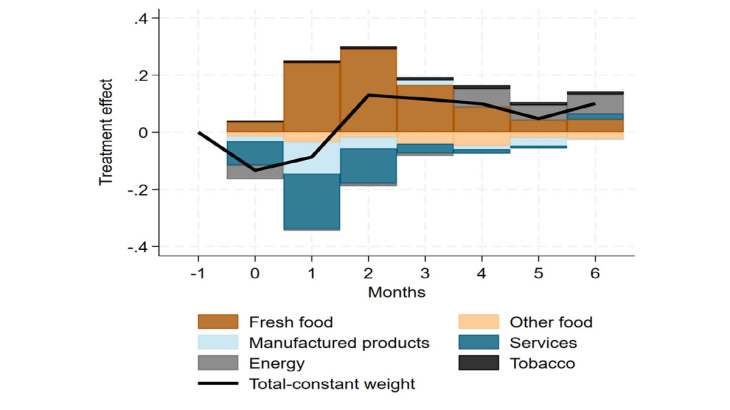

We find that weather-related disasters induce a temporary but statistically significant rise in headline consumer prices, with a peak at 0.5 percent two months after the disaster occurrence (Figure). The overall observed effect is driven by an immediate strong surge in the prices of fresh food products of 11 % after two months, which vanishes after four months. Prices of other food products also increase, but more moderately and in a more sustained manner (+0.3 %). By contrast, the prices of services and manufactured products decline moderately (and in a less statistically significant way), by about -0.2 %. The positive effects on food prices are likely to reflect negative supply shocks, as we observe a simultaneous decrease in agricultural employment. To the contrary, the negative effects on the prices of manufactured products and services are likely to reflect negative demand shocks.Our results point to small and temporary effects on headline inflation, mainly related to distortions of relative prices.

These effects translate into distributional effects through the heterogeneity in household consumption structure. Overall, the weather-related disasters increase temporarily inflation inequality, with a difference of up to 0.2 pp between the bottom and upper quintiles of the household income distribution. The rise in inflation inequality is primarily due to the fact that the weight of food in the consumption basket is higher for low income households.We also analyse the effects of the introduction of price cap policies, namely the Bouclier Qualité-Prix introduced in 2013. Price caps lower the impact response of price reactions to weather-related disasters in the sample period. However, cumulated over six months, price reactions are not significantly affected by the introduction of price cap policies, implying that the adjustment in the price level is just spread over the horizon of six months.

Keywords: Natural Disasters; Extreme Weather; Inflation; Disaggregate Inflation; Inequality; Price Gouging

JEL classification: E31, Q54