Do currency crises increase children malnutrition in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), and does it affect their socio-economic outcomes as adults? In this paper, we explore this question by combining data from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) for several hundreds of thousands of individuals across 57 EMDEs with the dataset from Laeven and Valencia (2020), documenting currency crises worldwide since 1970 at a monthly frequency. Our main variable of interest is height, which is commonly used as a direct measure of malnutrition in the literature, represents a key measure of children’s health, and is a good proxy for socioeconomic conditions and general welfare at adult age.

In this setting, we show, for a survey of children under 5, and using height-for-age z-scores (HAZ) based on World Health Organization (WHO) standards relating height to age in months by gender, that the occurrence of a currency crisis between their month of birth and the month of survey reduces their height by about 0.1 standard deviation. This effect is stronger for events occurring during the 12 months preceding the survey, but we do not find significant effect of shocks occurring in utero or before conception. This baseline effect reflects a higher prevalence of stunting (i.e. HAZ below -2). This effect is robust to controlling for potential confounding factors considered both prior to the currency crisis and during its occurrence, which can be macroeconomic (debt crisis, banking crisis, economic growth) or non-economic (conflicts, natural disasters). It is also unlikely to reflect the existence of differential selection into parenting between households, as it is robust to controlling for birth height, birth weight and mother’s height, and to controlling for same-mother fixed effects.

This effect is largely channeled through lower food affordability. Currency crises indeed have stronger effects on children’s height in countries that are net food importing developing countries (NFIDC) or that have a high level of undernourishment, and when currency crises occur in years of strongly increasing wheat prices. Part of the effect is channeled through inflation, which increases following a currency crisis. Controlling for the latter in our baseline estimation reduces the effect of currency crises by 20 to 35 %, and this reduction is observed only in NFIDC. By contrast, controlling for other macroeconomic variables likely to be affected by currency crises, such as economic growth, public debt, or official development assistance flows, does not affect the estimate of currency crises effects. We then document a decrease in the quantity and diversity of food consumed by children affected by currency crises. The occurrence of a currency crisis within the year preceding the survey decreases both the probability that children eat food during the day before the survey and the number of types of solid food they consume. This mainly comes from a lower consumption of nutrient-rich non-starchy food, often more expensive, and less caloric (namely fresh products such as fruits, vegetables, meat and dairy), while cheaper, more caloric starchy food (such as cereals, grains and roots) decreases by a smaller amount. This suggests that, facing a tighter budget constraint due to a currency crisis, households prioritize starchy food in order to maintain minimal caloric intake for their children. This likely induces a reduction of the nutritional quality of meals, and thus a higher prevalence of stunting. The reduction of food intake is paradoxically stronger for children of richer households. This might be due to the fact that poorer households have a lower initial caloric intake, making it more difficult for them to reduce their food consumption. This might also be explained by the fact that they are more often rural, and are thus more likely to eat local food, which is likely less affected by currency crises. Finally, we also test whether currency crises affect the probability that children access pharmaceutical products, and find no significant effect.

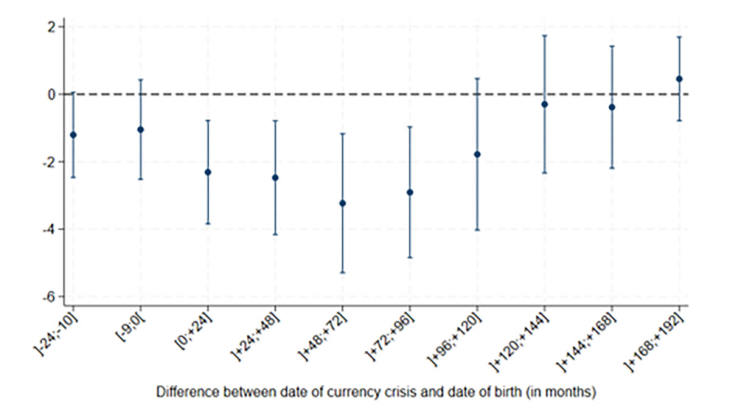

Currency crises occurring during childhood have persistent effects. Using a survey of adults between 20 and 30 years old, we simultaneously estimate the effect of being born between 2 years before and 16 years after the beginning of a currency crisis. We show that being born around a currency crisis reduces adult height by a maximum of about -3 mm (0.04 standard deviation, Figure 1). We estimate significant effects for crises suffered between 0 to 8 years old, with the maximum effect materializing for crises suffered between 5 and 6. As adult height is a strong predictor of other socio-economic outcomes, this suggests early exposure to currency crises have socio-economic consequences at adult age. We confirm this by showing that adults who faced a currency crisis during childhood were also less likely to complete secondary or higher education.

Keywords: Currency Crises, Malnutrition, Human Development

Codes JEL : F31, I14, J13, O15