The transition to a low-carbon global economy will require a strong increase in the use of critical minerals and metals. Whether the supply will be able to adjust to this increase in demand is an open question, and it is important to understand its determinants. Among them, prices are likely to be crucial. Indeed, an increase in the latter is likely to boost production in the long-run, higher expected returns fostering technological innovations and geological exploration. But it might also increase production in the short-run, through a change in the intensity or production. While it is important to understand the sensitivity of production to prices, especially as increased demand is expected to put upward pressure on the latter, there are few recent estimations of the price elasticity of supply, and they rarely focus on minerals that are critical to the energy transition.

In this paper, we assess this question by leveraging mine-level data from Jasansky et al. (2023), focusing for the period 2000-2019, on the production (in tons) of 8 minerals essential to the energy transition, namely cobalt, copper, lead, molybdenum, nickel, platinum-group metals, silver, and zinc. These minerals represent about 70% of the basket of the IMF’s Energy Transition Index, and their production in the dataset, based on the information of 318 mines located in 43 countries, covers more than 20% of global production over the period of interest. We examine whether the production of these minerals, at the mine-level, reacts to shocks on their global prices, on a time window ranging from 0 to 5 years. In order to estimate a proper price elasticity of supply, we focus on the reaction of production to price movements induced by mineral-specific demand shocks.

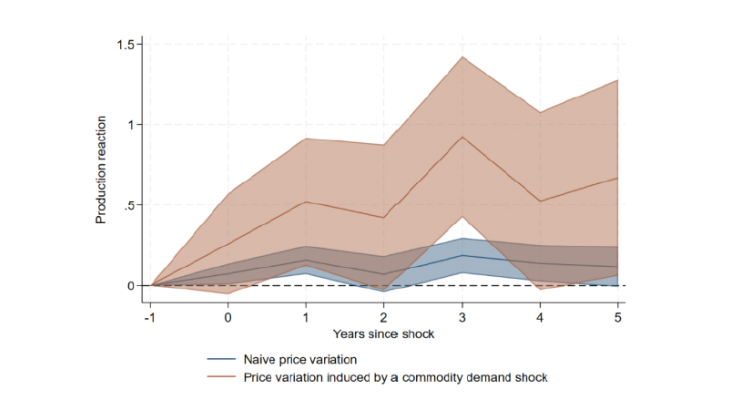

To do so, we first estimate, for each mineral, a 3-variable structural VAR model with sign restrictions, including global economic activity, global real mineral price, and global production, from 1912 to 2019. We define three types of shocks, that we identify through sign restrictions following Boer et al. (2024), namely aggregate demand shocks (having a positive effect on mineral prices, mineral production and economic activity), mineral-specific supply shock (having a positive effect on mineral production and economic activity, but a negative effect on mineral prices) and mineral-specific demand shock (having a positive effect on mineral production and prices, but a negative effect on economic activity). Based on this methodology, we isolate the variations of mineral prices that are due to a mineral-specific demand shock, and study the reaction of production at the mine-level, using a local-projection approach, and controlling for mine-mineral fixed effects.

Our baseline estimation indicates a rapid and strong reaction of production to price variations induced by a demand shock, with an elasticity reaching about 50% one year after the shock, which remains broadly stable up to 5 years. This result is robust to a large number of robustness checks, and appears larger than existing estimates. This difference might come from the fact that, contrarily to existing studies, our elasticities are based on micro-level production.

The estimates are heterogeneous across minerals, as silver, copper, and nickel drive the results. They are also affected by characteristics of the global mineral market, of the mines, and of their location. Regarding the characteristics of the global mineral market, we find that the price elasticity of supply is lower for minerals with a greater concentration of production (measured through a Herfindahl-Hirschmann index on mine-level production), but that the implementation of export restrictions measures does not significantly affect the reaction of production. Regarding the characteristics of mines, we find that the reaction is stronger for the primary mineral they produce (defined either in volume or in value), and that the production of non-primary minerals within a mine is more sensitive to the price of the primary-mineral than to their own price. Mines owned by more than one company, having larger proven reserves and producing more than one mineral also tend to have lower reactions. Finally, regarding the location of the mine, we do not find that local economic activity or proximity to transport infrastructure affects the price elasticity of supply, but we document that greater proximity to conflict reduces the latter. This partly explains a lower price elasticity of supply in Africa, which faces a stronger intensity of conflicts that other continents.

Keywords: Critical Minerals, Price Elasticity of Supply, Energy Transition.

JEL classification: C33, O13, Q3