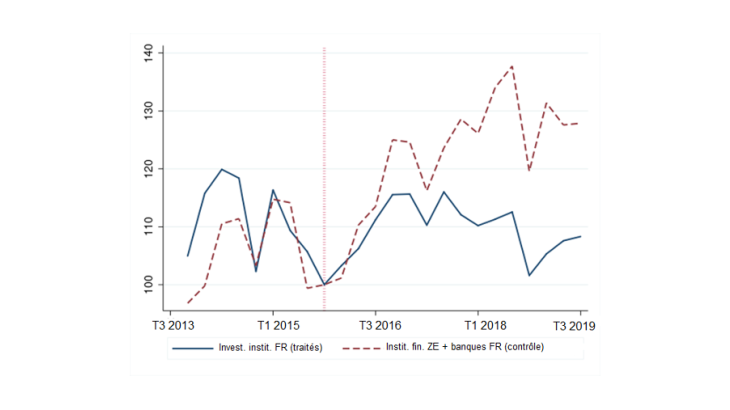

Note: The solid blue line corresponds to the total amount of fossil energy securities held by French institutional investors affected by the TECV law. The red dotted line corresponds to the portfolios held by other euro area financial institutions not subject to this law. Amounts expressed at market value, rebased to 100 in Q4 2015, just before the effective implementation of the regulation.

While it is now widely acknowledged that curbing global greenhouse gas emissions to reach the objectives set in the Paris Agreement of 2015 requires a major shift of global funding towards low-carbon activities, the way to achieve this re-allocation of private capital rapidly enough remains an open issue. Part of the debate revolves around making the carbon footprint of financial institutions and their exposure to climate risks more transparent to investors.

In this regard, a large number of initiatives for greening finance have flourished in the financial industry since 2015, urging their members to enhance the voluntary disclosure of their exposure to climate-related risks and/or to reduce the carbon footprint of their investments. A prominent example of such a move is the Task Force for climate-related financial disclosure (TCFD), a global initiative backed by the G20’s Financial Stability Board.

At the same time, regulators are increasingly considering implementing mandatory climate-related disclosures for financial institutions – for instance, through the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) or the recent endorsement by the G7 leaders of mandatory reporting along the lines proposed by the TCFD.

What would more stringent reporting regulations achieve?

In a new study we show that imposing climate-related disclosures on financial institutions actually leads them to divest themselves of carbon-intensive securities. We assess the effects of the French Energy Transition and Green Growth Act – the “TECV law” – whose Article 173-6 pioneered climate-related disclosure in Europe.

The law, which was passed in August 2015 in the run-up to the COP21, came into force in January 2016. It imposes new reporting requirements on institutional investors registered in France regarding their climate-related risk exposure and their efforts to mitigate climate change. While the list of required disclosures is comprehensive, investors have the choice between complying and explaining and can choose their preferred evaluation methods.

We study the impact of these new disclosure requirements in terms of portfolio adjustments, by focusing on investors' holdings of bonds and stock, issued by firms in the fossil energy industry (i.e., firms operating in the extraction, production and transport of fossil fuels). For investors subject to transparency requirements, divesting from securities issued by fossil energy firms is a relatively quick and easy way to, both, comply with new climate-related objectives and communicate to the public (by publishing for instance plans for exiting coal).

Monitoring the financing of fossil energies

In order to conduct our investigations, we first construct an exhaustive dataset of all bonds and stocks that were issued (and not yet redeemed or repurchased) by fossil fuel companies worldwide between the fourth quarter of 2013 and the third quarter of 2019.

We then analyse the holdings of these securities by euro area investors, using a database on security-by-security holdings by institutional sectors in Europe managed by the Eurosystem. We focus on the holdings of financial institutions, broken down into three sub-sectors: banks, insurance companies and pension funds, and all other asset management firms and mutual investment funds. The provisions of the TECV law explicitly target the last two sub-sectors, i.e. institutional investors, but not banks. In addition, the law only applies to institutions domiciled in France, and no similar legislation existed in any other euro area country before 2019. This enables us to construct a so-called "treated" group made up of French institutional investors targeted by the law and a so-called "control" group made up of French and foreign investors not subject to the reporting requirement within the euro area.

We compare, before and after December 2015, the holdings of fossil energy securities by these two groups of financial institutions. While the combined portfolio holdings of both groups move in a relatively parallel way before the new regulation, they diverge notably once the law has come into force (Chart 1). Holdings of fossil energy securities by French institutional investors targeted by the reporting requirement decrease sharply once the law has been implemented, compared to holdings by financial institutions not targeted by the law.

A significant effect that vindicates a wider adoption of the climate reporting obligation

The detailed econometric analysis we conduct confirms this intuition: the mandatory climate-related disclosure discourages portfolio investments in fossil fuels. The measured effect is statistically and economically significant: French investors targeted by the law reduced their holdings of fossil energy securities by some 40% on average, compared to the control group. Furthermore, they are also less likely to invest again in new fossil fuel securities.

The impact of this regulation is about twice as large for portfolio investments in companies exploiting mostly coal and unconventional fossil fuels. We also find evidence of a strong home bias in the reaction of euro area investors: treated institutions divest primarily from companies in the fossil fuel sectors that are domiciled outside the euro area.

These findings vindicate the planned extensions of mandatory climate reporting by financial institutions, in Europe and beyond, in addition to the voluntary disclosure. Indeed, the effect of “Article 173-6” that we identify after 2016 still holds out at the end of our sample in 2019, although many large financial institutions in Europe had by then joined initiatives of investors committed to fighting climate change.

In line with the findings of Bingler, Kraus and Leippold, our study suggests that a reporting obligation is essential to speed up the alignment of finance with the objectives of the energy transition.