- Home

- Publications and statistics

- Publications

- A clear and symmetric 2% inflation targe...

Post n°240. In July 2021, the ECB announced that its price stability objective is best served by a 2% inflation target over the medium term. This clear and symmetric inflation target reinforces the buffer against deflation risks and supports the anchoring of inflation expectations.

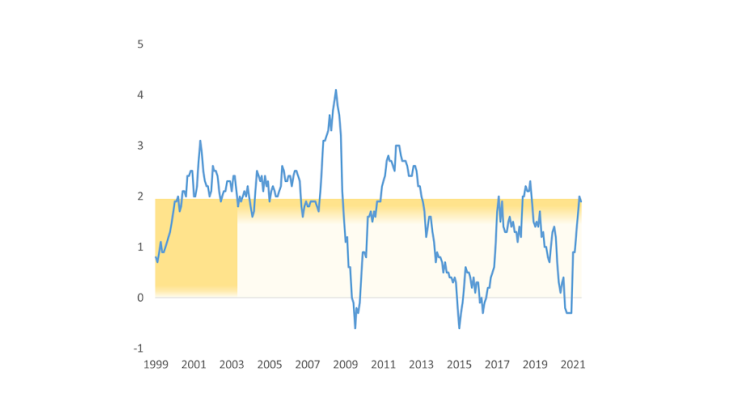

Notes: Inflation is the year-on-year change in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), in percent. The bands in yellow represent the different quantitative definitions of the price stability objective.

The primary objective of the European Central Bank (ECB) is to maintain price stability, as specified in Article 127 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. A precise definition of “price stability” is not spelled out in the Treaty, and it is up to the ECB to determine an operational formulation. Concluding its strategy review, the ECB Governing Council announced on 8 July 2021 that “price stability is best maintained by aiming for a symmetric 2% inflation target over the medium term”, with inflation measured using the HICP as before (see Chart 1). This outcome was based in part on analyses presented in ECB Occasional Paper No 269, which this blog outlines.

An evolution towards symmetry

The original definition of price stability announced in October 1998 was an “increase in HICP for the euro area of below 2%”. The word “increase” implied that falling prices, or deflation, was not consistent with price stability. If households and firms expect that goods and services will always be cheaper in the future, they will tend to delay purchases, reducing aggregate demand and employment. A high and volatile inflation rate, however, would be costly. By setting an upper limit of 2%, the ECB indicated outcomes anywhere in the open interval 0-2% would be consistent with the mandate.

When the Governing Council first reviewed the ECB monetary policy strategy in 2003, it kept this definition unchanged but clarified that its aim for inflation was “below, but close to, 2%”. With this clarification, it created an additional buffer against the risk of deflation.

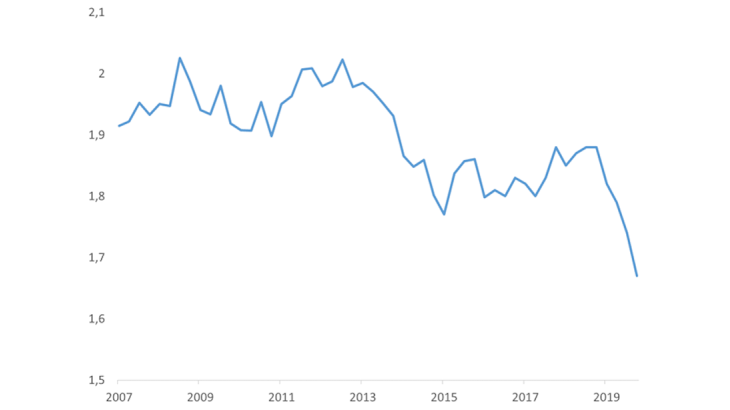

Note: Inflation is measured in percent per annum.

This definition served the ECB well for many years (Rostagno et al., 2019). It was helpful in stabilising inflation expectations when dealing with inflationary shocks. Inflation over the period 1999 to 2012 averaged 2%. However, from 2013 until 2019, inflation averaged only 1.1%, as the economy suffered a sequence of disinflationary shocks. Particularly worrying over this period was the decline in longer-term inflation expectations (see Chart 2). An emphasis on keeping inflation below 2% in the definition of price stability became a liability because, together with the policy rates being close to their effective lower bound, it gave rise to the perception that the ECB had a stronger reaction to inflationary shocks or greater tolerance of inflation below, rather than above, the target. This was not completely dispelled by repeated statements by the ECB President and the Governing Council that the target was symmetric. Surveys show that households and firms do not know the quantitative value of the ECB’s inflation objective (Bottone et al., 2021). All this argued for a clear and symmetric target.

Why 2%?

Staff of the Eurosystem provided analysis of the optimal level of the inflation target. On the one hand, an inflation rate away from zero has economic costs (e.g. it involves more frequent price changes), results in more volatile inflation (based on historical experience) and deviates from a literal understanding of “price stability”. On the other hand, having a positive inflation buffer mitigates concerns about measurement biases in the HICP, or the existence of downward nominal wage rigidities. A positive inflation target also provides a safety margin against the risk of deflation. For any given targeted inflation rate, nominal policy interest rates will be constrained by the effective lower bound more frequently and for longer periods if equilibrium real interest rates are lower (Brand et al., 2018). This reduces the room for providing accommodation during recessions. All else equal, the higher the inflation target, the larger the scope to use the conventional policy instruments, that is the short-term interest rates (Andrade et al., 2021).

The Occasional Paper recognises that identifying an optimal level for inflation is challenging. Nevertheless, many analyses suggest that an inflation buffer is if anything more important than in 2003. At the same time, it might be difficult for a central bank to establish the credibility of a new and higher target after having undershot the existing target for some time, especially given that the new target would be different from the one set by other major central banks. In addition, in the last decade central banks have resorted to unconventional monetary policy instruments (such as asset purchases, forward guidance on policy rates and targeted longer-term refinancing operations) to provide additional stimulus to aggregate demand when the policy rates were close to the effective lower bound. These instruments have been effective to support the recovery and bring inflation closer to target (Altavilla et al., 2021), even though their impact and possible side-effects are not well understood.

Overall, the Governing Council judged that 2% was an appropriate level, in line with that of other major central banks. At the same time, the Governing Council recognised that when the economy is close to the effective lower bound, especially forceful or persistent monetary policy measures are needed to prevent below-target inflation becoming entrenched. This may also imply a transitory period in which inflation is moderately above target.

The role of the medium term

The ECB’s Governing Council confirmed the “medium-term orientation” of its new strategy. This acknowledges that monetary policy cannot keep inflation at 2% at all times. Monetary policy takes time to affect inflation and there can be shocks in the interim (for example to energy prices or supply bottlenecks) that the central bank cannot easily offset. Setting a tolerance band around the target is an alternative way to accommodate the idea that inflation is volatile and cannot be fine-tuned in the short run, as some central banks do. However, the flexibility of the medium-term orientation already recognises that the appropriate monetary policy response depends on the origin, magnitude and persistence of the shocks hitting the economy – see section 3 of the Occasional Paper. Without prejudice to price stability, it also allows the Governing Council to cater for other considerations (such as employment and financial stability) relevant to the pursuit of price stability in its monetary policy decisions.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024