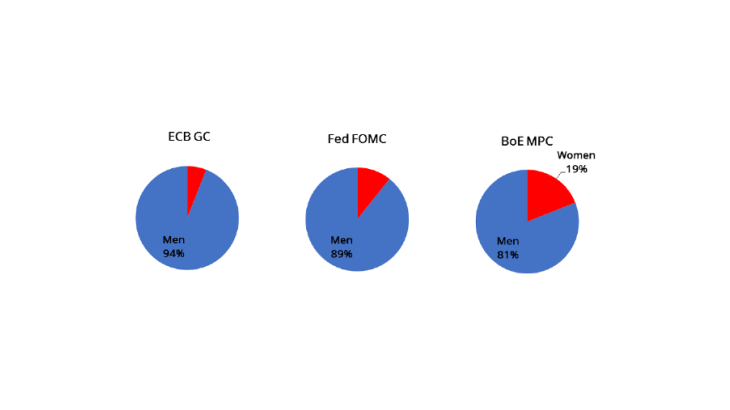

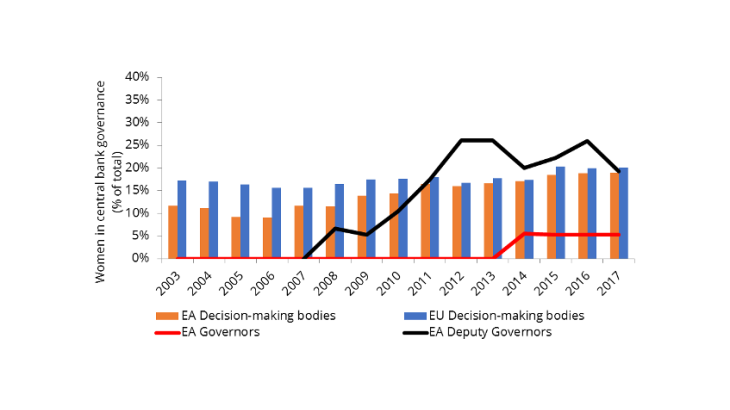

Initiatives are currently under way in many central banks to promote a more equal representation of women at the top. The ethical case for gender rebalancing in central banks governance is a sufficient reason alone as this is primarily about making the most of the pool of talent available to set monetary policy. But we could provokingly ask whether women have a different leaning to monetary policy objectives than men (see also a recent VOX EU post on this topic).

Are women in central banking hawks or doves?

From a financial analyst’s point of view, do women tend to assign more priority to fighting inflation (hawks) or to supporting more output growth and employment (doves)? We look at the case of the FOMC, using insights from a unique dataset that divides FOMC members into perceived hawks, doves and swingers, i.e. those who are perceived to have switched from one type to another (see Istrefi, 2018). This classification is based on a textual analysis of US newspaper articles since the 1960s, investigating how Fed policymakers are portrayed in terms of their policy leanings towards inflation and growth. About 20,000 articles or reports, from more than 30 newspapers and business reports of Fed watchers have been read to construct this measure. Looking at 130 FOMC members, the measure shows that 39% of them are perceived as all-time hawks, 30% as doves and 24% as swingers. The rest remained unknown. Within the FOMC composition, Reserve Bank presidents are perceived as more hawkish and the Board members as more dovish. In terms of gender, women (14 out of 130 members) are perceived more on the dovish side than men (57% versus 27%).

Beyond gender: education, early life experience, and political support

Does this mean women in the FOMC are intrinsically more dovish than men? Not necessarily. First, the sample of women is too small to assign statistical significance to these numbers. Second, a subsequent study using this classification (Bordo and Istrefi, 2018), highlights two important factors in moulding the policy preferences of these FOMC members: ideology and events that shaped their early lives. They show that the odds of being a dove are higher for those that studied in universities with Keynesian beliefs, like Harvard or Yale, were appointed to their position, mainly to the Board of Governors, by Democratic Presidents and were born in a period of high unemployment. This is equally true for men and women in the FOMC. Moreover, the majority of women in the FOMC (11 of 14 of them) started their tenure from the 1990s onwards, which is a period characterised by a dovish trend in male FOMC members as well.

Consider the case of Janet Yellen for instance, who served at the FOMC as Board Governor (1994 -1997), San Francisco Fed President (2004-2010) and finally Federal Reserve Chair (2014-2018). Yellen, a Yale graduate, was first nominated to the Board by President Bill Clinton in 1994, together with Alan Blinder (an MIT graduate). Both were expected to be doves on policy and were thus perceived during their respective terms at the FOMC. For instance, pending their confirmation from the Senate, the Financial Times referred to both of them as ‘inflation doves', alluding to their education in the Keynesian tradition and to their appointment by a Democratic president.

Besides, women perceived as hawkish or swingers have all but one represented regional Federal Reserve Banks. Interestingly, half of them have represented the Cleveland Fed, known for a high inflation-fighting appetite (currently Loretta J. Mester with voting rights in the FOMC for 2018). Thus, gender doesn’t seem to be a relevant indicator of policy orientation. When guessing FOMC members’ orientations, it is more informative to know from which university these members graduated, what great economic events shaped their early life, or who appointed them and for what position, rather than their gender.