Urbanisation in exposed areas and solutions provided by land-use and insurance policies

The global economic costs of natural disasters have risen dramatically over the last decades, reaching USD 190 billion in 2020, against USD 1.3 billion in 1970 (at 2020 prices) (Sigma, 2021). Besides the increasing importance of climate change, this trend is largely explained by the growing number of people and businesses located in exposed areas and the value of their assets (Hallegatte, 2012). For example, in Florida, in 2012, 80%, or USD 2.9 trillion, of the insured assets were already located near the coasts. In China, in 2004, 50% of the population and two-thirds of the agricultural and industrial product value were concentrated in the 8% of the land area located in the mid- and downstream parts of the seven major flood-prone rivers.

This growing urbanisation in exposed areas is partly due to amenities linked to risk: riversides are attractive. Perception biases, such as underestimating risk or forgetting past events, play their roles. Local public authorities may also fail to communicate on actual risks for fear that the attractiveness or the value of real estate assets might be adversely affected. Economic incentives matter: when households who settle in exposed areas do not have to bear the full cost of the risk as it is not priced into insurance contracts, this favours urbanisation. Our focus here and in our article (Grislain-Letrémy and Villeneuve, 2019) is on this type of free-riding. We limit our scope to the non-life losses from these disasters.

The solutions to control urbanisation in exposed areas combine land-use and insurance policies. Land-use policies sometimes lead to decisive actions, such as the acquisition by the Federal Emergency Management Agency of nearly 4,500 flood-prone homes in Missouri after the 1993 Great Flood. Insurance policies can also limit free-riding by making households and businesses located in exposed areas pay for the risk they take. For example, the earthquake insurance premiums in Japan or the flood insurance premiums in the United States increase with respect to the risk exposure. Even in these cases, the premium increase is regulated.

Risk capitalisation in property values and the impact of insurance prices

Asset values should reflect differences in risk. Thus, the value of property in a flood zone is depreciated by the real estate market. If insurance is available, the negative capitalisation originates from insurance premiums. Empirical studies based on the hedonic price method confirm that real estate markets value the capitalised flow of disaster insurance premiums (Bin et al., 2008, Harrison et al., 2001, MacDonald et al., 1990). Experience shows that real estate prices react more to insurance premiums revisions than to other risk revelations (Skantz and Strickland, 1987).

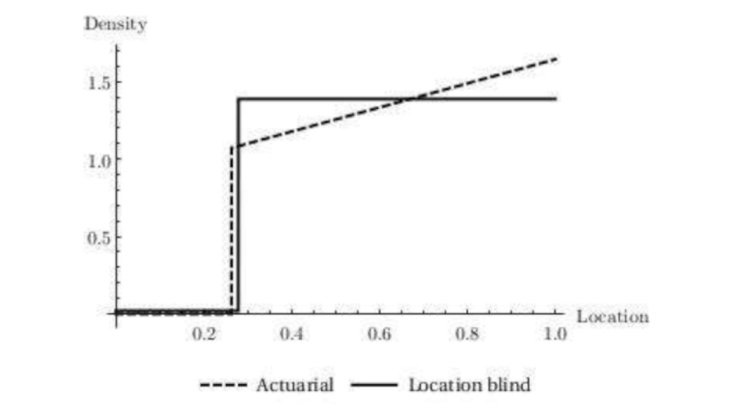

Insurance is often location-blind. The first type is disaster assistance by the state in Australia, China, and in many European countries, where private insurance is either non-existent or purchased by few households or firms. The second type is the legally non-discriminatory insurance pricing, such as in Denmark, France, Spain, or Switzerland. In most countries, this inefficient pricing of either of the two types is accompanied by construction prohibition.

Under location-blind insurance, and assuming that the insurance is complete, then all the properties become artificially equivalent, leading to greater urbanisation of the most risky places. In practice, this negative effect is somewhat mitigated by the fact that insurance is in reality incomplete.

A typical result of economic analysis is that the insurance premiums (price incentives) are, in principle, as efficient as the zoning approach (quantity regulation). Actually, prices and zoning are even substitutes at any scale. Zoning can increase degrees of efficiency in a territory uniformly treated by insurance; insurance tariff differentiations can make up for the imperfection of zoning.

Examining the power of red zone policies

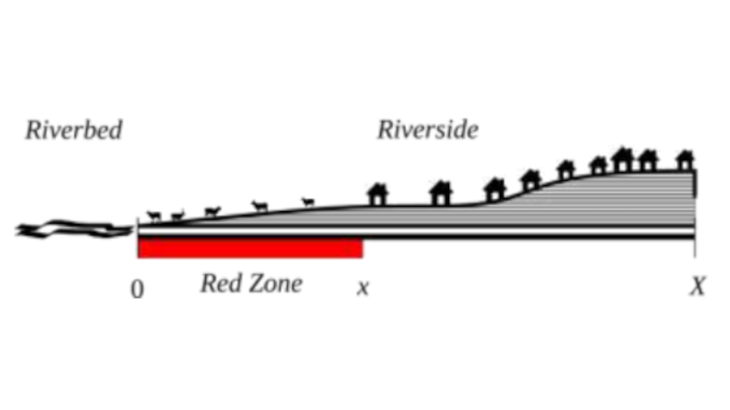

We investigate the most commonly observed policies with a prohibited red zone and a building zone without insurance tariff differentiation.