- Home

- Publications et statistiques

- Publications

- How to interpret the rebound in French G...

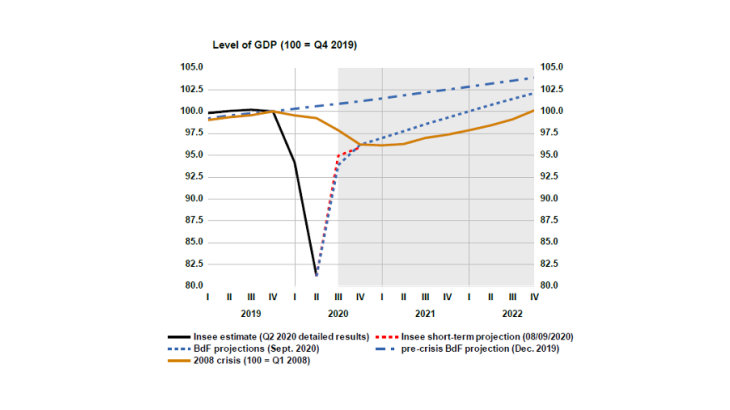

Post n°182. According to the Banque de France macroeconomic projections published on 14 September 2020, after declining by 8.7% in 2020, GDP growth is expected to stand at 7.4% in 2021 and 3.0% in 2022. Despite this apparently impressive rebound, the economic catching-up process should in reality only be very gradual. GDP should only return to its pre-crisis level at the beginning of 2022. This post provides a few explanations of these unusual growth rates.

Sources: Insee, Banque de France

How are the Banque de France projections made ?

The Banque de France publishes quarterly macroeconomic projections for France over a 3 to 4 year horizon:

- In June and December, these projections are produced jointly with the European Central Bank (ECB) and all the Eurosystem national central banks (NCBs) in the framework of the Broad Macroeconomic Projection Exercise (BMPE). These projections are thus the result of a collective process within the Eurosystem, based on technical assumptions common to all participants in the exercise (interest rates, oil prices, exchange rates, etc.);

- In March and September, the projections for the euro area published by the ECB are those made by its staff, without the participation of the Eurosystem NCBs. The Banque de France, for its part, produces its own projections for France, based on the Eurosystem's technical assumptions.

The projections are therefore chiefly conditional on technical assumptions, which leads to establishing alternative scenarios around the central scenario.

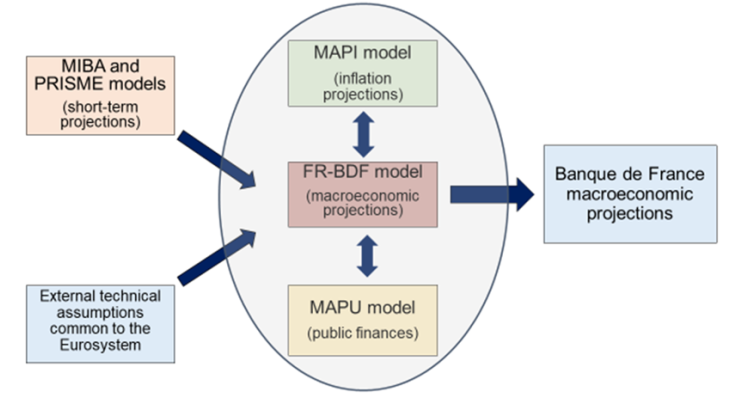

The Banque de France makes its projections based on a series of models (cf. diagram 1). A coherent medium-term scenario can then be constructed, by drawing on the information available in the short term. The FR-BDF semi-structural model is at the heart of the projection process through its interaction with the other models. Thanks to this large-scale model, it is possible to model the interactions between the major macroeconomic aggregates of the French economy and to project them in a structured manner over the forecast horizon. FR-BDF interacts with the MAPI (Model for Analysis and Projection of Inflation in France) and MAPU (Maquette Agrégée des Finances Publiques) models, which are satellite models more specifically dedicated to the analysis and projection of specific variables.

Source: authors, Banque de France

For the starting quarter of the forecast (i.e. the 3rd quarter of 2020 for the September 2020 projections) and possibly the following quarter, the short-term forecast is made using specific models that draw on the most recent information available, notably through business surveys. The MIBA (Monthly Index of Business Activity) model uses the most recent information available, in particular data from the Banque de France's monthly business survey (EMC), together with sectoral information from the PRISME (Prévision intégrée sectorielle mensuelle) model.

However, since the start of the pandemic, the Banque de France has adjusted its models for measuring short-term activity by mobilising new tools based on high-frequency information (credit card data, energy consumption data, etc.) and new questions in its business surveys (8,500 for the EMC), which make it possible to incorporate information as close to the field as possible.

The September 2020 projections are thus based on two essential sequences. Thanks to the short-term tools, it is possible to estimate activity levels for end-2020 and to set the "starting point" of the projections. In a more structural approach, it is then possible to use the model to draw a trajectory reflecting the medium-term behaviour of the economy considered most likely in view of the current shocks.

The rebound in growth in 2021, a quasi-mechanical consequence of the (de)confinement

The recession caused by the Covid-19 health crisis is totally unprecedented, mainly owing to the fact that a large section of the French economy was under lockdown for part of the 2nd quarter of 2020 for health reasons and not for economic reasons. This explains the sharp downturn and the rebound as soon as health restrictions were lifted. On the contrary, the 2008 financial crisis had not led to such a rebound (Chart 1). Thus, according to Banque de France and Insee surveys, after shrinking by 18.9% between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020, French GDP picked up by 16% in the third quarter of 2020.

However, focusing on growth rates rather than on activity levels can be misleading: despite historically high growth for 2021, the economic catching-up process should only be very gradual. Indeed, growth for 2021 expressed as an annual average consists in comparing GDP (i.e. the flow of value added or income generated by the economy) for 2021 with that of 2020. This comparison therefore depends not only on what will happen in the quarters of 2021, but also on what is expected for 2020, a year marked by a historically low point in the second quarter and an exceptional rebound in the third quarter. This is where the concept of "growth overhang" (see also Waechter 2020) helps to understand the order of magnitude of the expected growth rate for 2021:

- if the level of quarterly GDP remained at the level currently expected for the third quarter of 2020 until the end of 2021 (i.e. zero quarterly growth from Q4 2020 to Q4 2021), the average level of GDP in 2021 would still be much higher than the average level of GDP in 2020, so that, as an annual average, GDP growth in 2021 would stand at 3.4%;

- if the level of activity for all quarters of 2021 remained at the level expected for the fourth quarter of 2020, annual growth would stand at 5.3% in 2021.

The historically high figure for expected growth in 2021 (7.4%) is in fact partly "carried over" by the profile of activity in 2020. Of course, should a new, uncontrolled wave of the epidemic arise, leading to the adoption of very restrictive measures between now and end-2020, thus causing a downturn in activity in the fourth quarter, these calculations of carry-over effects for 2021 would become obsolete.

A projection surrounded by exceptionally large uncertainties

The first source of uncertainty is the GDP estimate itself up to the second quarter of 2020. Due to the magnitude of the shock, it is now more difficult for statistical institutes to properly measure activity and current estimates are likely to be revised in the coming months. The gradual collection of more precise information on the market sector will lead to revisions. The same holds true for non-market sector activity, of which general government activity is a good example. At this stage, Insee, in line with Eurostat recommendations, considers that the output of general government in volume terms declined during the lockdown on account of the fact that a large number of civil servants could neither travel to their place of work nor telework. However, this estimate may be adjusted in the future as more detailed data on the number of government employees who were not on site or teleworking become available.

The data available today, for all countries, are therefore still fragile. A major revision of estimates for past quarters could thus lead to a significant revision of the annual growth figures for 2020 and thus for 2021, even if the quarterly trajectory described for 2021 was correct.

Secondly, macroeconomic projections are even more than usual surrounded by a large number of economic uncertainties regarding the assumptions made about the international environment, interest rates, oil prices, etc. More fundamentally, there is considerable uncertainty regarding the models used, in the presence of a "structural" break in the behaviour of economic agents that our equations could not capture, which is more likely to occur in atypical periods such as today.

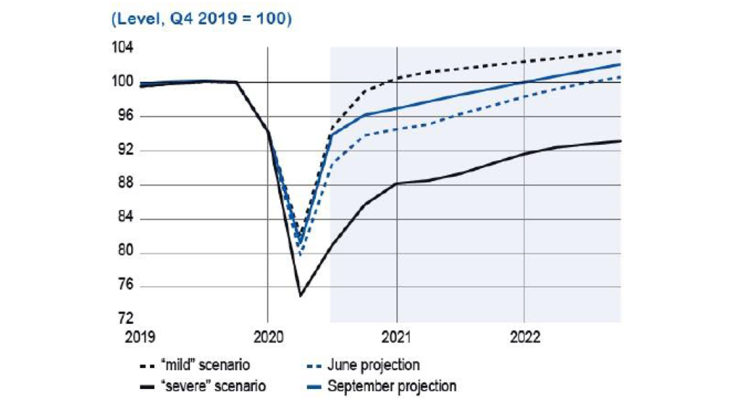

Finally, the projections are subject to an uncertainty of an unprecedented nature: the evolution of the health situation, in France as in the rest of the world, which remains very uncertain. This is why the Eurosystem has decided to publish three scenarios (mild, medium and severe, see Chart 2 for France), depending on the evolution of the pandemic.

Source: Banque de France

In conclusion, on the basis of the analysis that can be made as of today, it seems coherent to expect a very negative GDP growth rate in 2020, and then a historically very high one in 2021; however, this forecast for 2021 reflects to an unusually large extent the evolution of GDP expected in 2020, and not only that expected in 2021. This is why it is at least as important to reason in terms of GDP levels, rather than growth rates alone.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024