- Home

- Governor's speeches

- Making the post-Covid era a success for ...

Making the post-Covid era a success for the French and European economy

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 18th of January 2022

Speech of François Villeroy de Galhau, governor of Banque de France.

“Making the post-Covid era a success for the French and European economy”: summary

For two years, our economic debate has been dominated by the pressure of the Covid emergency, in a permanent present that masks our post-crisis structural challenges. Today, the global picture is one in which inflation is a source of concern, but growth is solid despite Omicron. In two years time however, our concerns should reverse, with inflation expected to normalise in line with a "new regime" close to our 2% target and growth expected to fall to below 1.5%. This is what we need to change. Gaining 0.5% of potential growth each year would enable us to overcome two permanent French problems: household purchasing power, which is increasing (somewhat artificially) at the expense of a deterioration in public debt; and an unemployment rate which, despite recent progress, is still well above the 5% level of near-full employment attained in many of our European neighbours.

What should we do? One third of this additional growth could come from changes at the European level, through the two major 'Schumpeterian' transformations: the digital revolution and the ecological transition. But in order to achieve this, three cross-cutting levers will be needed: revitalising the single market; providing equal access to training and skills in the southern countries, including France; and pooling our funding. Europe has on the one hand the resources, i.e. a savings surplus of EUR 300 billion per year, and on the other hand huge digital and ecological investment needs: to build the bridge between the two, it is urgent to speed up the Capital Markets Union.

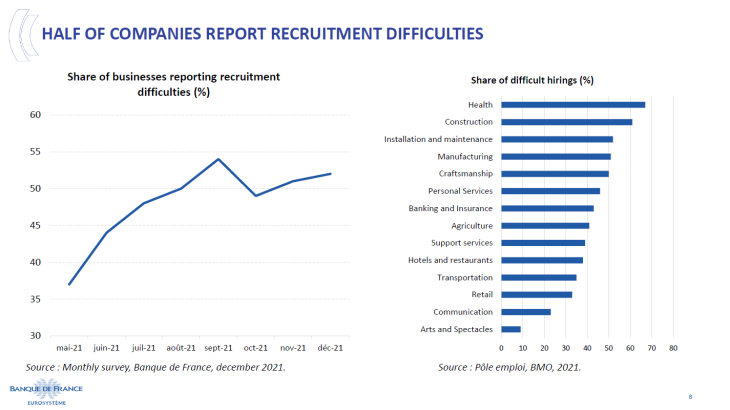

The remaining two-thirds of this targeted additional growth could be achieved by addressing two issues specific to France: primarily, inadequate labour supply. To increase potential growth, we do not lack public spending or capital overall, we lack labour. In France, more than 50% of companies are experiencing recruitment difficulties whereas there are still 2.4 million unemployed, including 600,000 young people: this paradox is socially unacceptable. France has almost 3 million fewer people in employment than Germany, and the majority of these are young and elderly people. In this respect, the levers of reform are: for young people, the strengthening of basic education and apprenticeships; for older people, a fair pension reform. And for all working people, professional training more focused on the key issue of skill enhancement; a reform of the unemployment insurance system that provides good incentives for long-term employment and work; and negotiated wage increases for jobs that suffer from a lack of attractiveness. These levers, several of which have already started to be implemented, must be combined instead of being pitted against, which is too often the case, and implemented with perseverance rather than remaining fleeting declarations. We could then aim for full employment within ten years and finally bring our debt under control.

Massive public debt is indeed the other major French challenge: after its legitimate increase in response to the Covid crisis, if current trends were to continue in the future, it would only stabilise at around 115% of GDP. This would not be sustainable, given the likely rise in interest rates, the need for ecological investment, and the possibility of a new crisis. We must therefore make it clear with regard to the many current proposals for additional spending or tax cuts that our country can no longer afford any further deterioration in its public finances.

A credible debt reduction strategy is possible by combining three ingredients: time – over 10 years, French public debt could be brought below 100% –, growth, associated with the aforementioned reforms but which would not be sufficient, and finally better control and efficiency of our public spending. This spending is now not only the highest in Europe but of all developed countries. I am not implying reducing it, by means of austerity, which is so dreaded. But I am referring to slowing down its annual increase: discussing the quality of spending could also ultimately be useful. Given the current crisis in public services, their necessary modernisation and mobilisation are not incompatible with performance and management; and spending on the future - from education to investment - has a better multiplier effect on long-term growth.

Ladies and gentlemen, dear teachers and students,

I am very happy to be with you again today, in this very important place of teaching and knowledge. I had the honour of speaking here in January 2020, on the then much disputed question of low interest rates. Two months later, the Covid crisis erupted, which not only rebuilt the consensus on these low rates, but also called into question all our forecasts and many of our common points of reference. Since then, we have been living under the continuous pressure of an emergency situation, in a permanent present that masks our structural challenges. I understand and share the suffering. But one day, we will overcome for once and for all this Covid ordeal: this is both an obvious wish for this new year, and a necessity. It is time for us to talk at last about the fundamental choices for Europe and for our country, and to do so, we must take a longer-term view.

I. A perspective that must go beyond the short term

As regards the short-term economic situation, I will therefore just make three remarks:

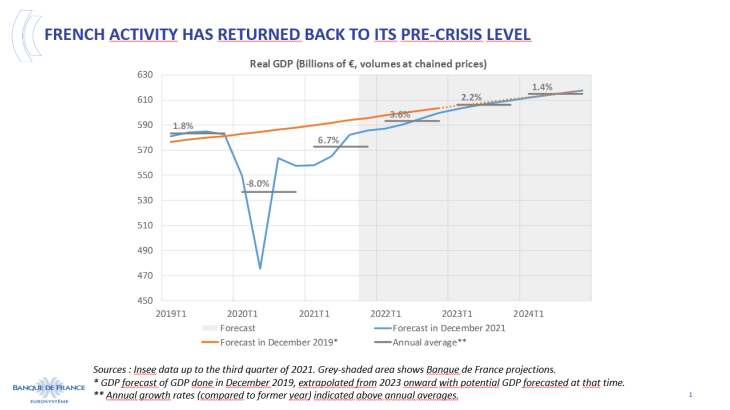

a) The French economy is currently proving resilient to Omicron and to the fifth Covid wave. Each of our monthly surveys confirms this, including that of the beginning of January: GDP has returned to its pre-Covid level since last August, earlier than expected and earlier than our European neighbours; the fifth health wave should not prevent significant growth in 2022, i.e. 3.6% in our forecast. The French economy should therefore return to its previous growth path by 2023 and Covid should leave few scars on the French economic fabric. Overall, the Covid crisis has been well managed economically by the public authorities. These very successes justify firmly resisting today a return to "whatever it takes": entrepreneurs are not meant to be subsidised for life.

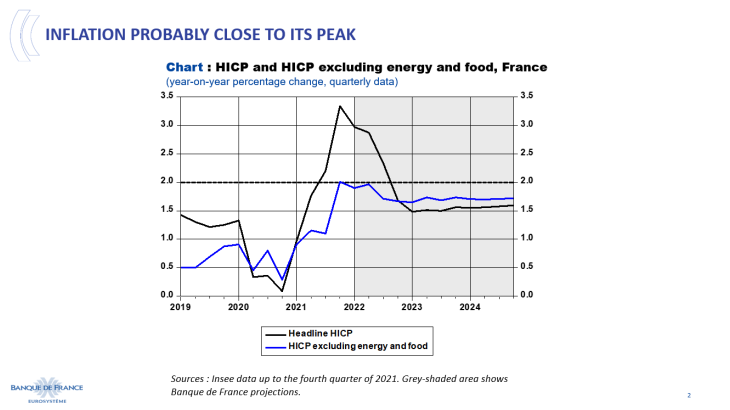

b) Due to this recovery in particular, companies are undoubtedly experiencing supply difficulties. They have little impact on the volume of activity (excluding the automotive sector), but push up prices, including those of manufactured goods. At 3.4% year-on-year at the end of 2021 (2.1% excluding energy and food), inflation in France is at its highest level since September 2008. This "hump" is bigger and longer than expected, but it should remain temporary: inflation in France should gradually decrease throughout the year, falling back below 2% by the end of 2022. This is a high-quality forecast; it is obviously not a dead certainty. We are keeping a very close watch on the economic data. Should inflation prove to be more persistent, rest assured that we will be willing and able to adjust our monetary policy more quickly, to ensure a return to our 2% objective.

c) In the next two years, however, concerns should reverse: inflation is expected to normalise in line with a "new regime" which would not be the too low pre-Covid inflation, but one close to our 2% target. Conversely, current growth, boosted by catch-up effects, is expected to run out of steam: according to our latest projections, growth in France should fall to below 1.5% in 2024. We should set a more ambitious target for potential growth, between 1.5 and 2%, i.e. a gain of half a percentage point over the spontaneous trend. Because we need the revenues from growth to finance our collective projects, especially ecological ones, and our welfare, this is not inconsistent with rethinking the drivers of growth. This ambition would also make it possible to better reconcile an increase in household purchasing power and the containment of public debt, whereas we have so far sacrificed the latter in order to somewhat artificially ensure the former. The Banque de France is entitled to discuss this, because monetary policy cannot ignore economic imbalances, nor can it compensate for them in the long term. And I am speaking this evening with all the independence that this institution enjoys: when the central bank provides facts and its expertise, it is free of any political influence and respects the democratic process which, fortunately, is then responsible for the choices.

This half percentage point of potential growth can be achieved by a medium- to long-term reform path: the efficient firefighters of the crisis must gradually hand over to the architects. A third of the necessary progress could be achieved through two European-level transformations (II) – via investment, digitalisation and the associated productivity gains –, the rest would depend on two challenges specific to France (III).

II. Two Schumpeterian transformations for Europe

Europe, like the rest of the world, will have to achieve two major transformations in the next decade: the digital revolution and the climate transition. The Covid crisis has obviously accelerated the former, and fortunately has not slowed down the efforts regarding the latter.

Compared to the rest of the world – and in particular the United States – our Europe is lagging behind with the first transition, and still ahead with the second. But it suffers above all from a structural handicap: its lack not of economic weight – which we have, together – but of speed; Europe has unfortunately had less growth than the United States for the past thirty years, and less capacity for economic renewal. In a speech last March at the College of Europe in Bruges, I voiced the wish that we should finally reconcile the two great European economists of the 20th century: Keynes – who has provided us with much inspiration in the Covid crisis – and Schumpeter – the man of innovation, whom we will need in order to achieve these two transformations. They are a difficult challenge, of course, involving the restructuring of part of our productive apparatus, but also a source of opportunities and growth.

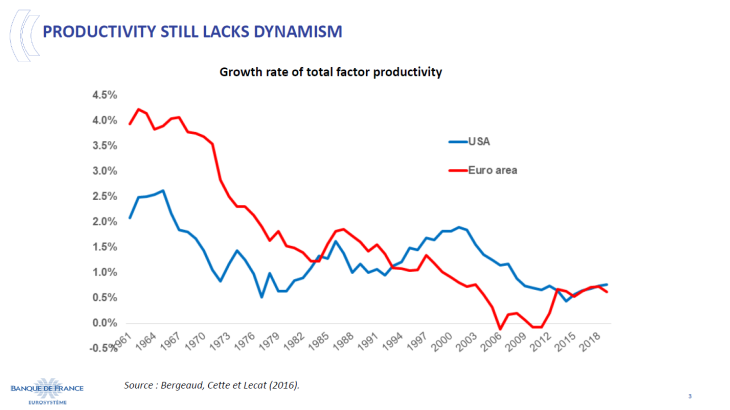

First, on the digital revolution: technologies have been slow to show their full potential in terms of productivity, which has remained sluggish for two decades in the euro area. However, it is potentially at a turning point, with the latest advances in AI, biotechnologies or telework-related reorganisations - after a lag which corresponds to the process of appropriating these technologies by the economic fabric (investment, training, etc.).

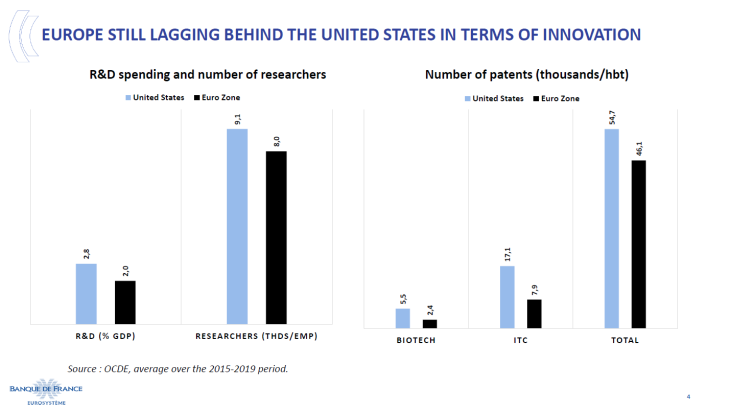

Europe will have to seize the opportunity of this productivity growth pool. However, it is still hampered by a lack of innovation and slowness in adopting these new technologies, particularly compared to the United States. We spend less on R&D (2% of GDP compared to 2.8% between 2015 and 2019), have fewer researchers and have filed fewer patents, particularly in biotechnology (2,400 compared to 5,500 over the 2015-2019 period) or information and communication technologies (7,900 compared to 17,100).

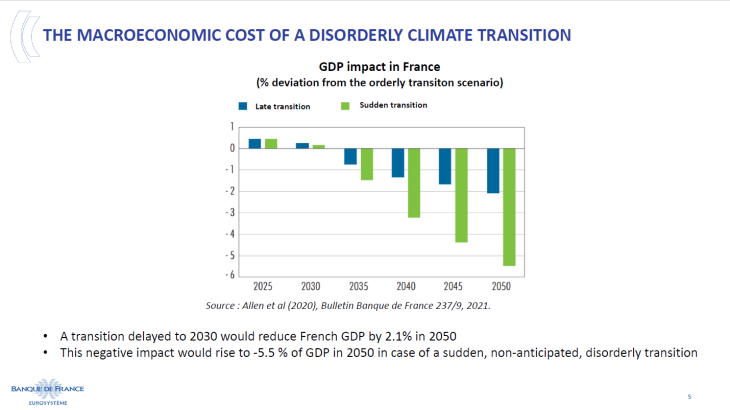

The climate transition, for its part, is an absolute necessity at the global level. Its macroeconomic impact will largely depend on the transition strategy chosen: the faster and more orderly its implementation, the less it will cost in GDP percentage points. For instance, according to the Commission, the EU plan would have an overall neutral effect on real GDP by 2030, a forecast deemed too "techno-optimistic" by Jean Pisani-Ferry. According to Banque de France simulations for our country, a disorderly transition would lead to a loss in GDP of up to 5.5% by 2050 compared to an orderly transition scenario.

To achieve these two transformations, we Europeans must more than ever unite our forces. And in this respect there are three "cross-cutting" levers that should guide our economic agenda: combining our clients, our talents, and our funding. Our clients are the single market, one of the largest in the world with 450 million people. This is not just the legacy of Jacques Delors. Thirty years on from 1992, we must have the courage to revitalise the single market and optimise its power by combining its different components in a much better way: freedom of movement, of course, but also regulatory power. We could use the power of regulation, in particular to steer innovation, as illustrated by the regulation of data, where Europe is at the forefront.

Our talents and "human capital" reflect the strong correlation between growth and education. We have some of the best education and professional training systems in Europe - and you are the best proof of that! But there are significant differences: in the southern EU countries, including our own, there are more low-skilled workers - Spain and Italy have twice as many as Sweden, as a share of the adult population - and fewer high-skilled workers – France has half as many as the Netherlands or Finland. This largely falls within national remits, but should be pursued within an upward-levelling European convergence: namely the Northern European solutions, including a much greater development of apprenticeships and professional training.

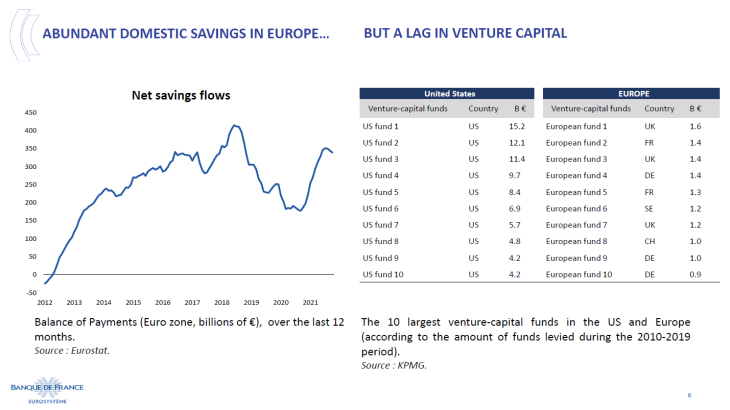

Lastly, by pooling our funding. I mean, partly, public investment programmes, such as those enabled by the famous "Next Generation EU", that decisive breakthrough from the Covid crisis. But a private driver is at least equally important: Europe must be able to harness and redirect its domestic savings, which are the largest in the world; in recent years, we have had a surplus of domestic savings over investment of almost EUR 300 billion per year. These savings should be channelled towards the equity financing of companies, which is a method of financing that is particularly well suited to innovative projects – which are inherently riskier and require long-term support, but which are also more profitable if successful. Our lag vis-à-vis the United States in this area is striking: the largest European venture capital firm appears to be three times smaller than the 10th largest US one. The technical agenda has been identified, but politically is not very clear and is far too slow in its implementation: it is the Capital Markets Union (CMU). On the one hand, we have resources – savings – and on the other, the investment needs of companies: we must decisively accelerate a European financial ecosystem that better allocates the former to the latter, if we want to finance the forthcoming digital and environmental revolutions.

III. Two challenges more specific to France

I would now like to discuss with you the two medium-term challenges that are more specific to our country. I am referring to our insufficient potential growth related to our inadequate labour supply, and excess public debt.

1) Potential growth and labour supply

Let's start with two clarifications. First, I am aware that the word "growth" has become ambivalent, as for some people it may carry more environmental risks than economic promises. GDP growth is not sufficient: it must - and can - be greener and fairer. But it remains essential for financing the European social and environmental model in which I strongly believe; degrowth would kill it.

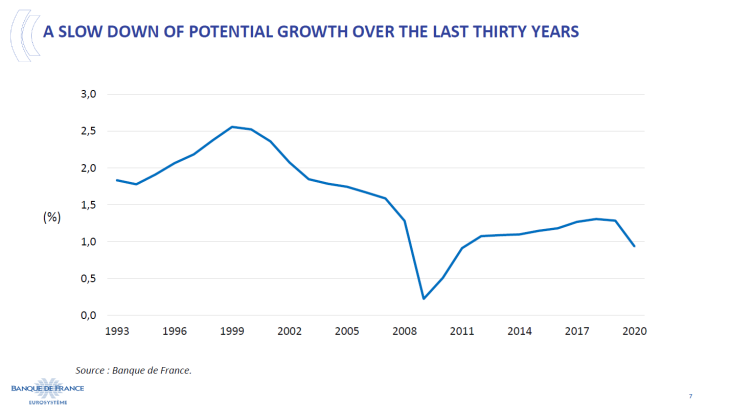

Second, it can be difficult to measure potential growth – the economy’s "cruising speed" outside of cyclical variations – because it is not a directly observable variable. At the Banque de France, we currently estimate annual potential growth at around 1.1% to 1.2% only, a figure that has remained fairly stable for the past ten years, after being halved over the past thirty years. Other estimates creep up to 1.35%, but they all hit a ceiling of between 1 and 1.5%, which is clearly insufficient.

Our growth potential is strongly linked to the way in which our production factors are used. In France, we do not lack capital overall - both public and private investment is rather high - but we do lack labour, the supply of available labour to employers. The most striking symptom of this is the recruitment difficulties reported by 52% of companies , with around 300,000 unfilled jobs, even though France still counts 2.4 million unemployed, including 600,000 young people. This is an economically unacceptable paradox, but even more so socially.

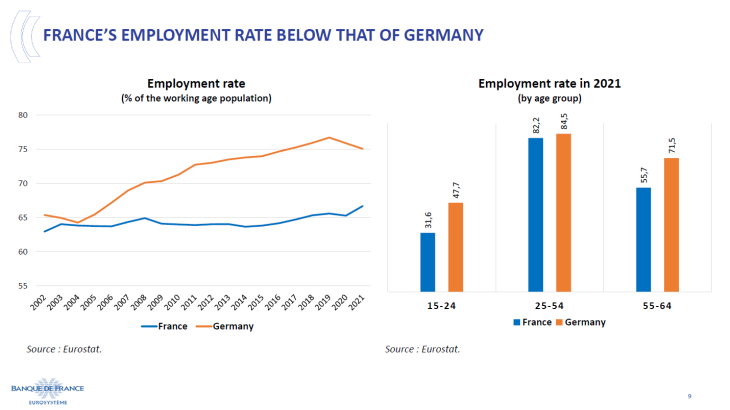

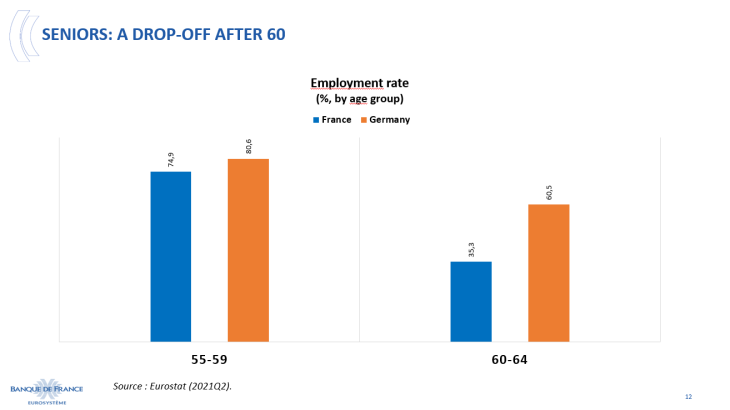

There is no greater priority than to get out of this French impasse, and in order to do so, to understand the problem by comparing our situation with that of Germany, which is at full employment (with an unemployment rate of 3.4%). While hourly productivity is similar, the average number of hours worked per capita is 10% higher in Germany. This difference is largely due to our low employment rate. While in the mid-2000s, our employment rate stood at 63%, which was roughly identical to the German rate (64%), it is now clearly lagging behind even though it has started rising (67% compared to 75%). This gap is partly due to the more widespread use of part-time work and work-study schemes in Germany. Nevertheless, for a working-age population of just over 40 million people, this gap represents a shortfall of close to 3 million jobs, which mainly concerns young people (1.2 million missing jobs) and seniors (1.3 million). So let's first talk about young people, then seniors, and then about the measures for all working people.

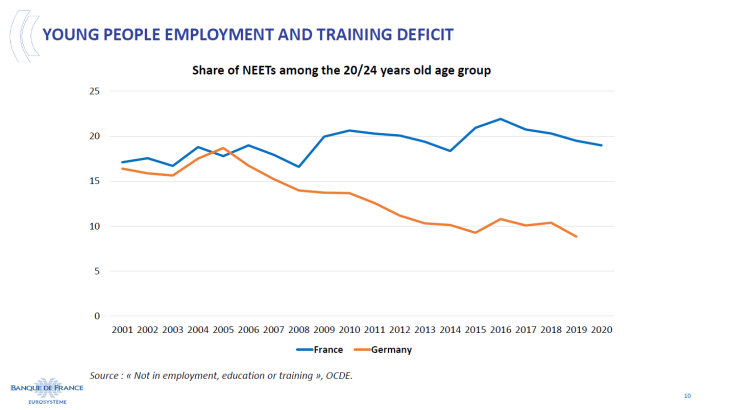

For the past decade, the share of young people who are not in employment, education or training (the so-called NEETs) has remained stable overall. We must therefore first do our utmost to stop the slow erosion of basic skills observed in the various international surveys (PISA, TIMSS).

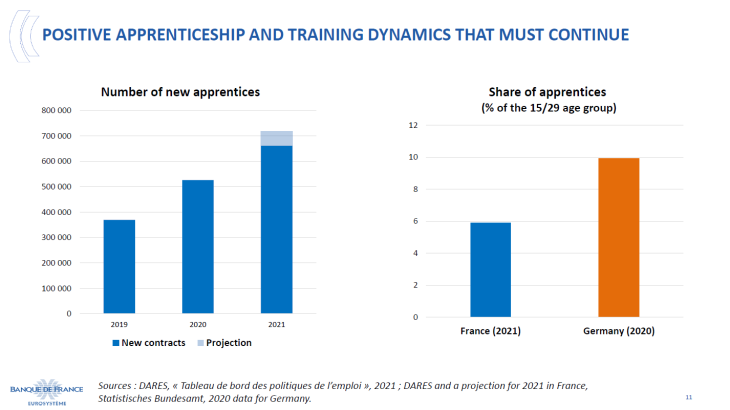

We must then ramp up the recent takeoff, since the 2018 Avenir Pro law and the 2020 1 jeune 1 solution plan, of apprenticeships, a fantastic tool for training and professional integration. The record number of close to 700,000 new contracts signed in 2021 must be just a starting point, from which to rethink the financing of work-study programmes.

As regards seniors, France lags behind in terms of the employment rate and this gap widens as people approach retirement. This is another economic reason – in addition to ensuring the smooth financing of the old age insurance scheme – why it is necessary to reform our pension system. This reform must be fair, and companies will have to make more room for older workers.

There remain three measures in order to raise the supply of labour for all workers:

- beyond apprenticeships for young people, vocational training for all. The Personal Training Account, resulting from the 2018 reform, has proved a great success (demands for training have increased by 40% compared to 2019). However, it will have to be optimised, in order to control its costs and above all to better steer it towards skill needs, in particular in the digital and industrial professions of the future. I have noted that, on the key issue of skill enhancement, France is still among the European laggards;

- by discouraging the repetitive and unjustified recourse to short-term contracts, including by some employees themselves, the recent unemployment insurance reform provides better incentives to work and to manage companies' human resources in a long term perspective. It will be necessary to assess whether it is both sufficiently effective and sufficiently fair;

- of course, there remains the issue of wage increases when it comes to enhancing job attractiveness. These are currently highly expected by our fellow citizens in the face of the inflationary hump; but we must prevent the return of a general price-wage spiral, which would be a loss for all. Nevertheless, for certain jobs where there is a deficit not in skills but in attractiveness, wage increases and negotiated improvements in working conditions are the key.

All these levers for influencing labour supply must be combined, instead of being too often opposed to one another in our public debate. They must be used with perseverance, rather than remain fleeting announcements. Only then can we find the other two missing thirds to gain the half point of potential growth in five years. Only then can we hope to achieve a 5% unemployment rate in ten years. And only then, and I'm coming to this point, will we finally be able keep our public spending under control.

2) Public finances and debt

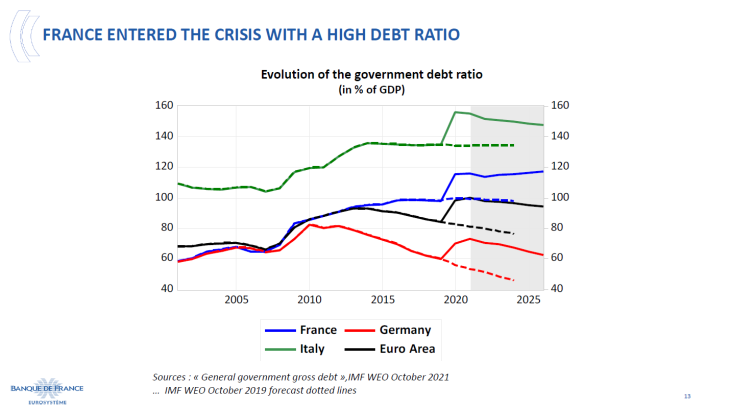

The figures on public debt are well known. The shock caused by the health crisis has led to a historically high level of debt, slightly below 115% of GDP in 2021, as, alas, we were starting from a pre-crisis ratio that was significantly higher than the average for the euro area.

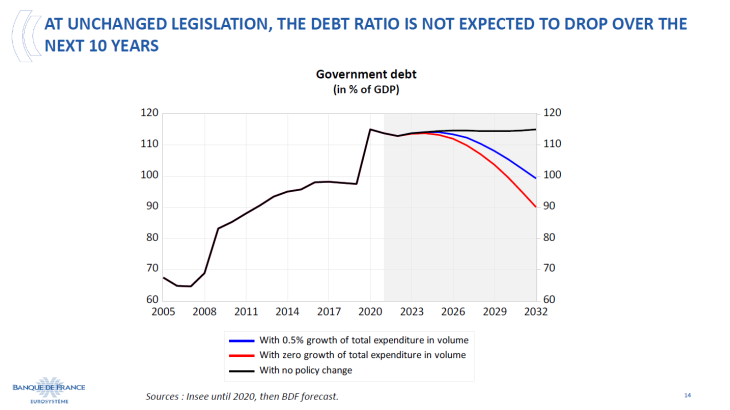

If the current trends of the past ten years are continued in the future - low potential growth, increased public spending in volume terms of over 1% per year, deficits still above 3% for several years – this debt ratio will at best only be stabilised. At best, because the public debate today is awash with proposals for new spending and additional tax cuts. The reality is that our country cannot afford either. Speaking with the voice of an independent institution, I would like to remind you that we cannot further worsen our public finances.

This simple stabilisation is not sustainable, for several reasons. First, because it would be irresponsible to bet on the continuation of extremely favourable interest rates. A rise of merely 1% in interest rates - which is not an extreme scenario - would cost EUR 39 billion per year after 10 years, i.e. the equivalent of the current defense budget. Second, because France must be prepared to face another crisis in the future, and in any case to face spending shocks such as the ageing of the population or climate change. We cannot forever pass the bill on to the next generation, i.e. to yours: sooner or later, this would cause a political and social crisis, or a crisis of confidence among international investors.

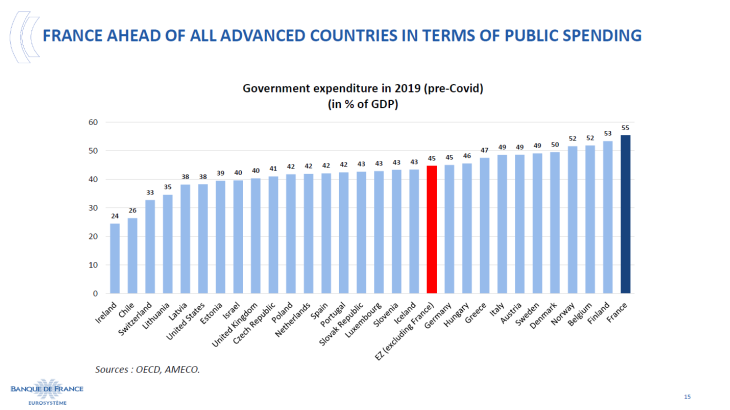

Indeed, it is easy to criticise, but hard to act. However, a credible debt reduction strategy is possible by combining three ingredients. All of them are necessary, because none of them is sufficient on its own. The first is time, acting over the long term, while starting rapidly as soon as the Covid-19 crisis ends in 2023. Over the next ten years, we must bring France’s public debt down to at least below its pre-Covid-19 level, i.e. below 100% as clearly as possible. The second ingredient is growth, to be raised by the abovementioned reforms. The third ingredient, which is also essential, consists in improving the efficiency and control of our public spending, which accounts for the highest share of GDP not only in Europe but in all developed countries.

Discussions on this issue often become very sensitive: in France, more than elsewhere, public sector reforms are easily associated with austerity, or even with a liberal ideology of which they would be the Trojan horse. However, Sweden, which is not reputed for being a liberal country, has managed to lower its public spending to less than 50%, while we have increased ours. This is the French paradox: we are always denouncing an austerity that is, however, a long way off. I am passionately convinced of the need for a public service, and affected by its current crisis: its necessary modernisation, its re-legitimisation, recognition for civil servants, is not incompatible with its capacity to perform and innovate, on the contrary. The transformation of the Banque de France is a modest but real example.

The idea is not to reduce public spending overall, but to stabilise it. Bringing spending growth down to 0.5% per year from 2023 onwards would lower the debt ratio to 100% of GDP in ten years, assuming the rate of tax and social security contributions remains constant - I insist on this condition; stabilising our spending in volume terms would enable us to reduce our debt even further, to 90% of GDP. The target to be set is obviously a matter for democratic debate. But the most important thing is that the targets set for this "overall spending limit" actually be respected, which unfortunately our country has never been able to do in the long term.

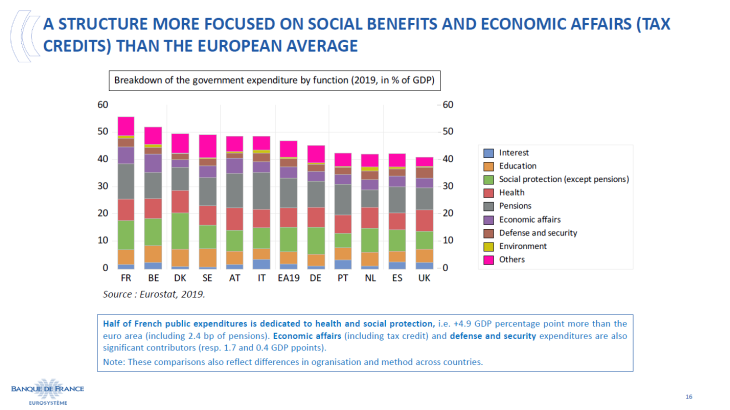

The choice of priorities or savings to be made also legitimately belong to the political debate. I would just like to point out that the key issue of the quality of spending is the blind spot in our budgetary debate, whereas it can guide us here. Economic analysis shows that spending for the future – most investment, education, research – has a much better "multiplier" effect on growth over time than simple current spending. A comparison with our European neighbours, which share the same social model, also points to some areas where our public costs appear to be significantly higher: certain social benefits, economic aid – including tax credits – and the presence of multiple layers of local and regional authorities.

None of the issues I have brought up here are easy. But everything is possible, and most of it depends on us. It doesn’t depend on anyone else, on globalisation, or even on Europe. A reform drive is guaranteed to produce results, as long as it is comprehensive, long-lasting – effective implementation over several years counts for more than the initial announcement – and fair. The gains then benefit everyone, and first and foremost those who are out of employment today and the most disadvantaged, who must be assured of a national solidarity that is finally financed over the long term. Our challenge is thus to finally project ourselves once again beyond the very short term. To conclude with Henri Bergson: "To act freely is to retake possession of oneself; it is to place oneself back in pure duration ". Good luck to our dear country, and thank you for your attention.

Updated on the 27th of November 2023