- Home

- Governor's speeches

- Launch of the NGFS Conceptual Framework ...

Launch of the NGFS Conceptual Framework “to guide action by central banks and supervisors on nature-related risks”

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 7th of September 2023

Paris, 7 September 2023

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Ladies and gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure to introduce, together with DNB’s President Klaas Knot, this NGFS conference that launches its conceptual framework on nature-related risks.

One year ago, we were together in Amsterdam for a pioneering conference on biodiversity from a central bank and supervisor perspective. At the time, our grasping of nature-related risks was roughly the same as on climate change some years earlier, and we acknowledged the need to refine our understanding and methodology. Indeed, our economic reliance on natural resources such as wateri, and more broadly on services provided by nature and, at the same time, the impact our economies have on nature, are becoming more and more obvious and are increasingly documented. As Ravi Menon, Chair of the NGFS, stressed it recently, “along with the climate crisis, the nature crisis is the existential challenge of our times. We cannot focus on one and hope the other will take care of itself.”ii

The new conceptual framework released today by the NGFS therefore marks an important milestone. It offers a shared language and sketches out a common method to assess nature-related financial risks and ensure that our collective work is both consistent and joined up. The common understanding we have reached together is both science-based and geared toward bridging the gap with assessing the economic and financial implications of nature-related risks. As Frank Elderson recently put it, “this is not some kind of a flower power, tree-hugging exercise. This is core economics.”iii

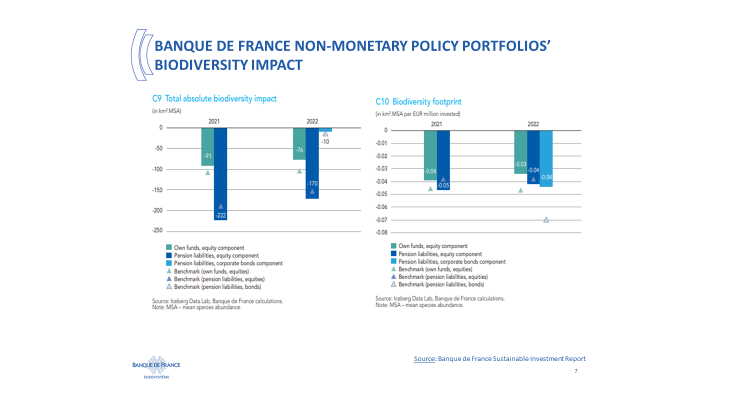

According to one estimate, reversing the decline in nature loss could require approximately 500 billion dollars per year until 2030, while the world currently spends less than 150 billion dollars on nature conservation and harmful subsidies represent 300 billion dollarsiv. Whatever the right figures, the gap is such that it is all the more important that financial actors start acting on nature-related risks to shift nature-blind financial flows. At Banque de France, we have started doing so through our sustainable investment policy by partnering with a data provider to carry out a detailed assessment of impact on biodiversity of the equity and corporate bond components of our non-monetary portfolios.

As you can see, the impact of our equity portfolios on biodiversity has decreased in 2022 compared with 2021, which is good news. It is a forceful demonstration of Banque de France’s strong commitment on environmental matters, and of the concrete impact of the decisions taken to reallocate accordingly the amounts we invest. It is a first step, but every journey has a start.

Let me strongly commend Emmanuelle Assouan and Marc Reinke, the two co-chairs of the task force and all its members for this decisive step. Thanks to them, the NGFS has laid the foundations that will allow central banks and supervisors to start taking into account operationally the degradation of nature in our mandate. Their work can give us confidence that we will address six challenges and next steps ahead of us:

- Some stress the need for more certainty in methodologies to kick off, saying that this topic is new, too complex, because of the intricacies of natural processes, their strong local dimension, or the absence of a single nature-related metric akin to CO2 equivalent. And we must honestly acknowledge what we don’t know yet, as I did last year, and our gaps on data and scenariosv. But uncertainty shouldn’t and cannot mean inaction. We can capitalise on our climate work to leapfrog some steps.

- Some sceptics would also have us believe that there is a trade-off between nature action and climate action. Obviously, climate remains the number-one priority; previous work of the NGFS has firmly established the relevance of climate-related risks for central banks and supervisors. Despite the growing impact of climate change, I have some concerns that this priority is at risk of fading away, as observed in the most recent G20 and international discussions, due also to the increased polarisation of political debates around climate and environmental issues in the United States. Europe is ahead; the rest of the world shouldn’t lag behind. But as central bankers and supervisors dealing with financial stability and price stability, we know complex and interrelated problems between climate and nature should be managed jointly: the framework elaborates on that in its “Phase 1” about the identification of physical and transition risks.

- To correctly assess nature-related risks, financial practitioners then need the right data and metrics, the choice of which will require further work; beyond the Mean Species Abundance per square kilometre currently used, we need to go further as not all nature-related risks are captured by this biodiversity indicator – think of water availability for instance. And practitioners also need shared concepts and a common language. The work of the NGFS provides a first common ground for a science-based understanding of how nature related risks can affect the economy and the financial system.

- Future new steps include dedicated scenarios – a challenging task as it is to make sure that they incorporate the hazards that expose us to the highest or more impactful risk. Among various possible physical risks, we will have to assess whether we should focus first on an Amazon dieback, on droughts in high income countries or on drops in crops yield globally. When considering transition risks, understanding the potential disruptions associated with removing harmful subsidies and/or protecting 30% of land and sea, as agreed in Kunming-Montreal, is a challenge.The NGFS is currently working to build appropriate narratives, but also to assess the capacity of existing models to quantify these narratives, accounting not only for direct impacts but also for the indirect ones across the value chains. The outcome of this work should be released in December, and will pave the way for the development of nature related scenarios relevant for the financial sector. The development of these scenarios is a priority as they will underpin the nature-related stress tests we know we will need to conduct, as for climate today, within a few years.

- Recommendations on ways to correct current biases in economic models, which tend to assume that nature’s contributions to economic activities can be substituted by more manufactured capital and labour, and are thereby largely unable to assess the impacts of many potential physical and transition patterns or hazards, placing us at odds with scientific findings. These recommendations will be provided in the above-mentioned report to be published by year-end.

- Last but not least, coordination will be key, because nature-related risks are a global issue – we are lucky to have Klaas Knot here, as Chair of the FSB. We need to work together, across public and private sectors, across borders. I will just reiterate one near term priority: we need interoperable standards on nature to facilitate and amplify prudential actions. The International Sustainability Standard Board (ISSB) has just closed a public consultation on its future Agenda, among which was a proposed focus on biodiversity, ecosystems and ecosystem services. Meanwhile, the European Commission finalized in July its reporting standard on disclosure requirements related to biodiversity and ecosystems, based on the work of the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG). I hope that the work undertaken by the Commission and EFRAG, but also by the NGFS will serve as a source of inspiration for the ISSB.

Let me conclude with Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States who dedicated to preserving natural resources in his country – an innovative thinking at the time, which led him to create many wildlife programs.

As early as 1907, Theodore Roosevelt wrote that “to waste, to destroy our natural resources, to skin and exhaust the land instead of using it so as to increase its usefulness, will result in undermining in the days of our children the very prosperity which we ought by right to hand down to them amplified and developed.” In our 21st century, it is high time to take care of our natural resources, for our children’s sake – and ours as well. I thank you for your attention.

iVilleroy de Galhau, F., Biodiversity, macroeconomics and finance: what we do know, what we don’t know yet, and what we have to do, speech, 29 September 2022

iiS&P Global (2021). Water stress is the main medium-term climate risk for Europe’s biggest economies.

iiiMenon, R, Bending the curve of nature loss (keynote remarks at the COP15 Finance and Biodiversity Day), 14 December 2022

ivElderson, F., Interview with the Financial Times, 8 June 2023

vDeutz et al. (2020). Financing nature: Closing the global biodiversity financing gap. The Paulson Institute, The Nature Conservancy, and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability.

Updated on the 21st of November 2023