- Home

- Governor's speeches

- Europe and Japan: our common strengths a...

Europe and Japan: our common strengths and challenges in a highly uncertain world

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 15th of November 2022

Special Lecture at the Waseda University – Tokyo, 15 November 2022

Europe and Japan: our common strengths and challenges in a highly uncertain world

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Ladies and Gentlemen, dear teachers and students, minasan konnichiwa,

It is my personal pleasure to be in Tokyo with you this afternoon, and I would like to thank warmly President Aiji Tanaka and the distinguished Professors Saito, Shizume and Elwood for their kind welcome. I am glad to see such a diverse audience – I especially greet Wakatabe-san, Deputy Governor of the Bank of Japan, as well as Shimizu-Sensei, a dear and honourable friend of France. I already had the pleasure of delivering a speech in this very Okuma building the last time I came here five years ago. Unfortunately, the world has become more dangerous and unstable since, especially in this year 2022. I will echo my previous speech in which I stressed the need for active multilateralism: this is even more accurate today in these turbulent times. But I will go into more details about the common challenges faced by Europe and Japan today (I). However, we also share key levers for success, which lie in our shared strengths, and in our ability to learn from each other (II).

I. In a highly uncertain world, Europe and Japan are faced with several challenges

a. The differentiated impact of three successive external shocks

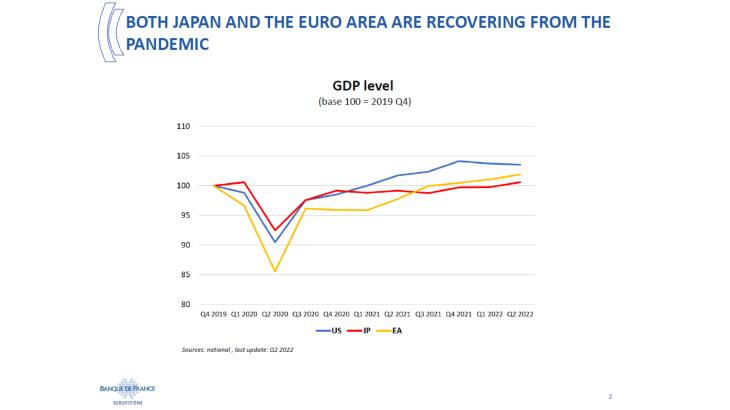

1) To start with, the pandemic has had a larger but shorter impact in Europe and in the US. In Japan, the pandemic caused a smaller drop in GDP due to the less stringent lockdown, but there was also a slower recovery thereafter due to some differences in terms of Covid strategies, notably in travel restrictions affecting tourism: GDP returned to is pre-pandemic level in Q2 2022 in Japan compared to Q4 2021 in Europe.

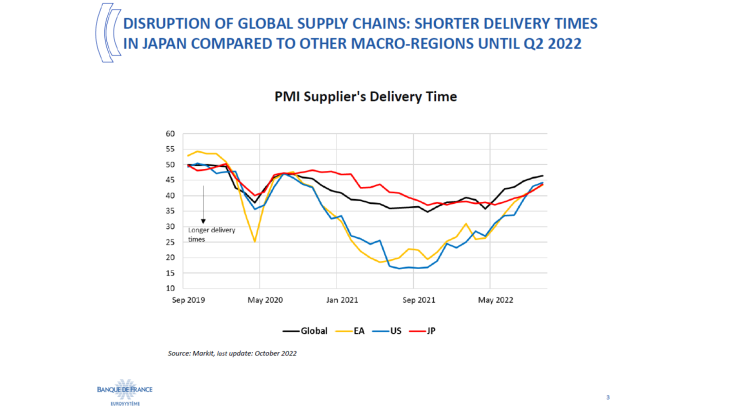

2) The global recovery after the lockdowns was accompanied by the disruption of global supply chains, which affected both Europe and Japan, but according to different timelines: Europe was more severely impacted than Japan as measured by delivery times, however its situation improved fast after September 2021. The Japanese economy is characterised by a significant offshoring of production to China, which means that it might have been more affected by China’s renewed lockdowns in the recent period.

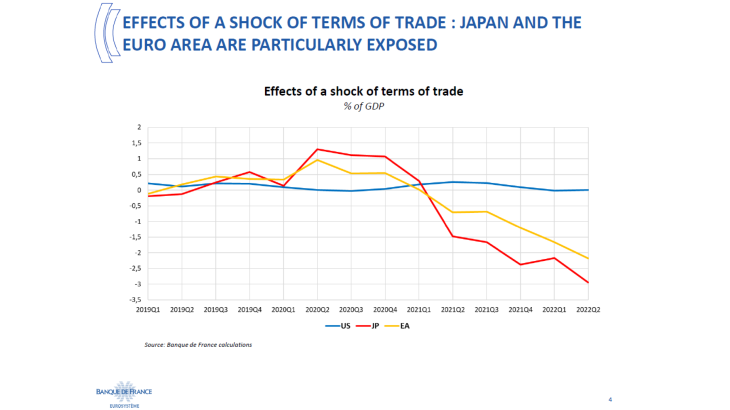

3) The invasion of Ukraine by Russia has added to the global uncertainty stemming from supply chain disruptions and hikes in energy prices. Europe, whose dependence on Russian fossil fuel products amounted to 18% [of its total primary energy consumption], has been sharply hit by skyrocketing wholesale gas and electricity prices, which have only been partly mitigated by government measures. Despite a lower direct reliance on Russian oil, Japan has also been affected by rising energy and commodity prices. As a result, terms of trade have sharply deteriorated in both areas.

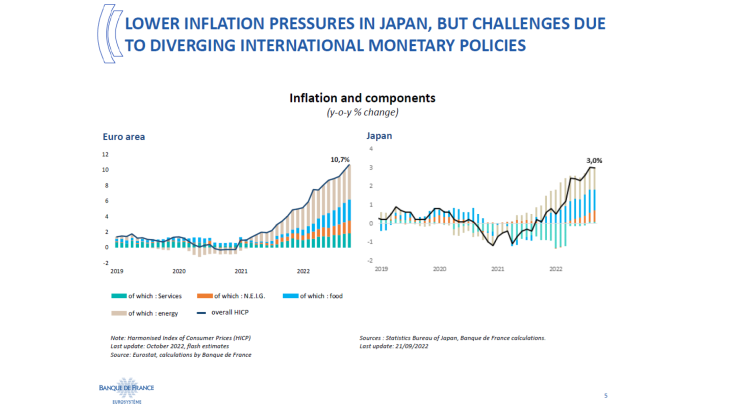

The conflict in Ukraine obviously clouds the economic outlook. It has also caused a large upturn in inflation, initially driven by the surge in energy prices: in October, euro area inflation reached 10.7% after 9.9% in September. But it is now becoming more broad-based and domestic: core inflation reached an historical high at 5.0% in October. In Japan, inflation pressures are much more moderate: CPI inflation rose to 3% in October, with core-core inflation remaining below the 2% target. These differences translate into monetary policies: the ECB has substantially withdrawn its monetary policy accommodation, while the Bank of Japan has reaffirmed its commitment to maintaining an accommodative stance. The difference of pace, and sometimes divergence, between monetary policies around the globe – starting with the US – bakes into the foreign exchange markets and exerts downward pressures on the euro, and even more on the yen.

b. Our common structural challenges

Beyond these shocks – which are the focus for public authorities – both Japan and Europe face structural challenges that also deserve serious attention and action. Many of them are common to both areas.

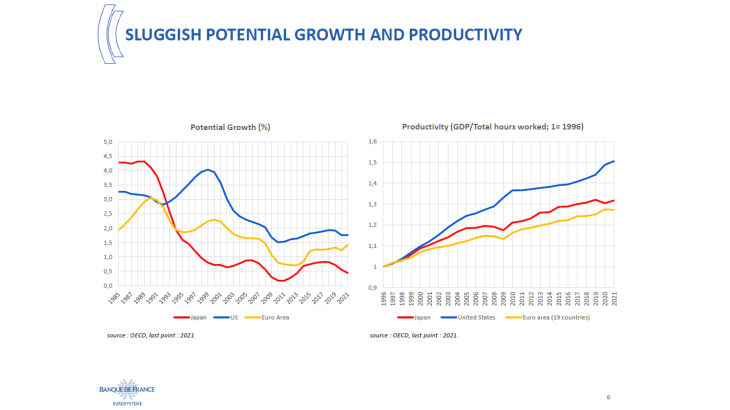

Our first common challenge relates to our growth potential, which remains below 1.4% in the euro area, and is estimated at around 0.4% in Japan;[i] in both cases this is rooted in sluggish productivity compared to the United States.

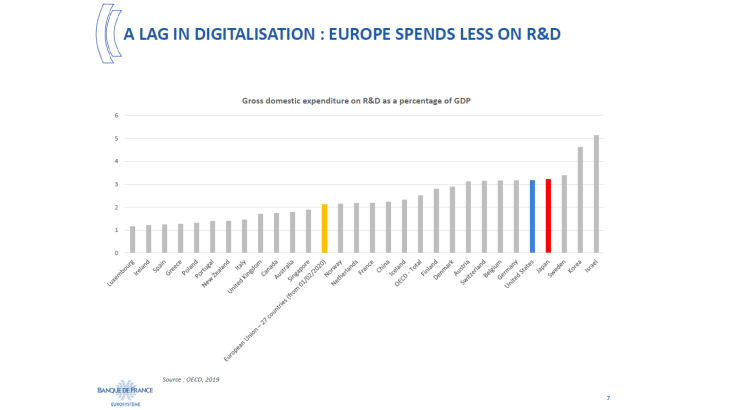

One of the common causes is the slower pace of digitalisation in our economies, and particularly in the adoption of information and communication technologies (ICT). The euro area especially has fewer researchers and has filed fewer patents in this area, while Japan – despite being a leader in various technology frontier – still lags in the adoption of digitalisation in businesses and government procedures, such as e-commerce or cashless payments.[ii] This is partly due to sub-optimal financing: on the one hand, Europe spends less on R&D than the United States for example, while in Japan private investment in ICT is especially low in small and medium businesses. This calls for more efficient financing of both our economies – which have a substantial financial surplus – notably through enhanced capital markets.

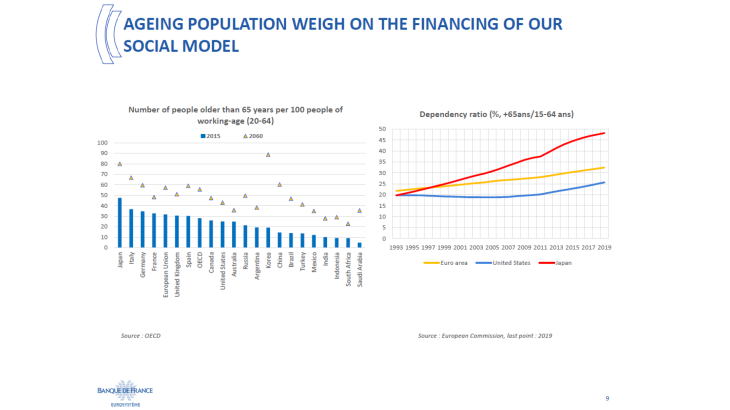

Another root cause is the core issue of labour supply. Both areas are experiencing major recruitment difficulties: in Japan, this stems from demographic trends which are causing a decline in the workforce, while in Europe the issue is more paradoxical given the higher level of unemployment in some countries: we have to further enhance vocational training and education for the younger. In both areas, increasing labour force participation is a priority, especially for the elderly.

Looking ahead, raising potential growth is a major issue, but on condition of making it greener and fairer. The climate transition is indeed an absolute imperative; Europe and Japan have accordingly set ambitious carbon-cutting targets and have both committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. This raises serious transition policy challenges, starting with the compatibility path between our climate targets and the current energy crisis, which has increased reliance on fossil fuels, at least in the short run.

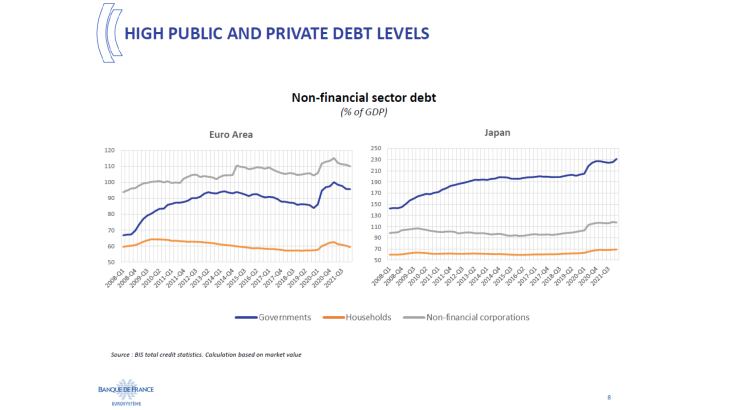

Finally, another common challenge facing Europe and Japan is that of high public and private debt. Public debt especially stands at more than 200% of GDP in Japan, and at 96% in the euro area – but above 100% in many countries, including France. While it is not in itself a pressing sustainability issue, it is an obvious intertemporal and intergenerational issue: fiscal policy must, in the long run, first stabilise and then diminish the burden of public debt. In the present financial market context, high debt levels can, however, become a potential source of financial vulnerability, which we will continue to monitor.

II. The levers for success lie in our shared strengths

a. Our shared values and the defence of multilateralism

France and Japan share undeniable assets to tackle these challenges. Let me here draw from one of the most famous Japanese children’s tales, that of Momotaro. On his way to an island, he befriended three animals: a dog, a monkey and a pheasant, that helped him defeat demons. These companions can been seen as symbols of the strengths that will help Japan and Europe to rise to their challenges; in other words, our common levers for success.

First, the pheasant is a symbol of abundance and promise: it can be taken as representing Europe and Japan’s age-old cultures of illustrious science, philosophy, literature to which we are deeply attached and of which we are rightfully proud. This awareness of a rich history also provides a long-term vision which is undoubtedly an asset in the current context of successive shocks and crises. Heightened uncertainty and the continuous pressure of emergency threatens to shift attention from our long-term challenges. We must never lose sight of our objective of structural reforms: they would increase both our short-term resilience and our long-term potential.

Second, the dog, as a symbol of devotion and loyalty, can be linked to our respective models of social progress, featuring high standards of infrastructure and public services. Far from being a weakness, I deeply believe that our social model is a source of resilience: we especially saw this during the Covid crisis. We are, however, confronted with the challenge of stabilising its costs and securing its sustainable financing in the context of an ageing population.

Third, the monkey, which was once seen as a messenger of gods and a sign of good luck in Japan; let me here draw a parallel with the universal values of human rights, state of law, and democracy. These shared values are the common basis for both our foreign policies. Both Europe and Japan are key drivers of multilateral discussions in the various international forums; and Japan is about to take the Presidency of the G7 in December. I believe that cooperation at the global level is the only way forward to tackle many of today’s challenges, starting with the climate and ecological transitions. However, in the current context of exacerbated geopolitical tensions, we must remain pragmatic and also take into account the imperatives of strategic autonomy and the strengthened resilience of our value chains.

Beyond our shared strengths, Europe and Japan also have a lot to learn from an enriched dialogue with each other.

b. Learning from Japan

First, Japan is a great source of inspiration for our western culture: its cultural influence can especially be felt in France where a “Japan exhibition” is organised every year in Paris. In France, 1/8th of books sold is a manga – which makes us one of the biggest consumers of manga in the world. Japan is also internationally recognised for its rich gastronomy, and for its refined and minimalist design for example. These “Japanese trends” in western consumption are the result of the successful development of Japan’s soft power. This is a fruitful example of a channel of influence and growth that Europe could exploit, as another major centre with a rich and multifaceted culture.

Japan remains an innovation leader. It is at the technological forefront in many industries, for example in industrial robotisation. Japan has achieved numerous successes in boosting productivity at big businesses – by contrast with small businesses – through major organisational innovations such as lean management and just-in-time delivery. In seeking to close its own innovation gap, Europe could draw from this example.

Finally, these turbulent times of war and threats of disruptions to energy supplies in Europe bring me to a more unfortunate example of Japan’s strength: Japan successfully overcame the Fukushima incident in 2011. This human and ecological disaster also translated into a brutal disruption of the energy supply, which was only partially offset: energy consumption was forced to decrease by 10%. Japan durably adjusted to this situation: ten years later, it still operates with a lower energy supply than in 2010, with a limited impact on long-term GDP.

c. The underestimated resilience of Europe

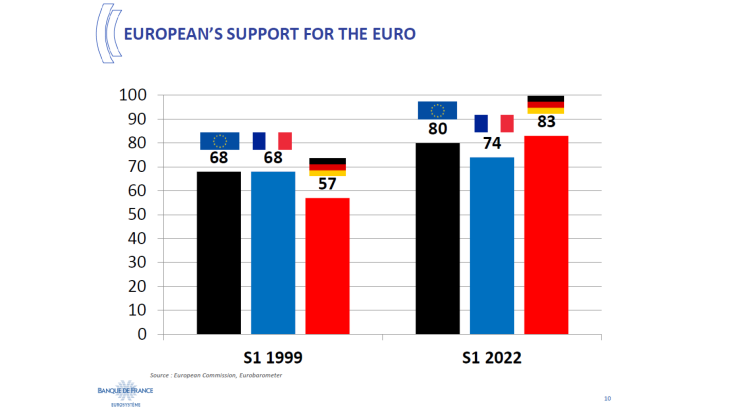

The background of the energy crises leads me to reflect on our European assets, and the reasons why we will succeed through these hard times. Europe is often criticised as being too cumbersome because of its 27 members and its elaborate institutional system. But Europe has delivered numerous great achievements. To remind you of a few of them, let me start with the outstanding success of the euro: it is recognised and used globally, as both a store of value and a means of trade. The euro is not simply an elite project; it is also a popular success supported by 80% of our fellow citizens[iii].

Second, we in Europe share the tremendous asset of the largest single market in the world, removing internal borders and regulatory obstacles to the free movement of goods, capital, services and people in the European Union. Third, despite its apparent complexity, Europe boasts an efficient decision-making process between the Commission, the Council, and the European Parliament. It has a genuine capacity to deliver, as demonstrated by its pioneering legislation on the climate or on crypto-assets for example; it took only a year and a half for the EU to agree on the main outlines of the profound transformation that climate change demands.

Europe is a prime model of cooperation that successfully overcomes difficulties, growing stronger at each crisis in the past; it will continue to do so in the future with the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis.

To conclude, I would like to quote a famous Japanese author Natsume Soseki : “Words are not meant to stir the air only: they are capable of moving greater things”.[iv] Let’s hope that these words will effectively translate into a better reality, both for Japan and Europe. Arigato gozaimashita, mata aimasho. [Thank you very much, see you again.]

[i] According to OECD estimated.

[ii] IMF, Selected Issues, Japan, April 2022.

[iii] Eurobarometer, summer 2022.

[iv] Kokoro, Natsume Soseki (1914).

Updated on the 27th of November 2023