Central banks must set monetary policy under substantial uncertainty on the economic outlook, as well as the effects of their own policies. To this uncertainty they often react by attenuating their policy response, or by changing it only gradually. Brainard (1967) provided a rationale for this cautious approach to policy-making. In his seminal paper, he formally derived what came to be known as the Brainard principle: although a policy-maker who is uncertain of the economic outlook should act as if his best expectation were a sure outcome (Theil, 1957), a policy-maker who is uncertain of the effects of his own policies should act less than he would under certainty.

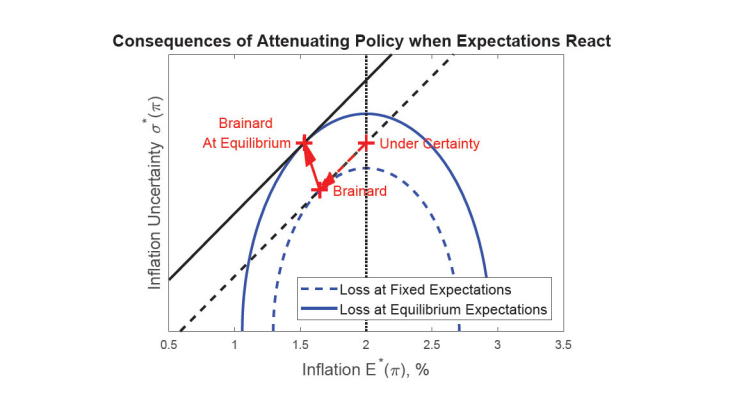

We show that the Brainard principle, while a wise recommendation for policy-making in general, runs into a pitfall when it is applied to a central bank setting monetary policy. For concreteness, we focus on interest-rate policies. When a dis-inflationary shock hits, the central bank can push inflation up by cutting interest rates. The Brainard principle would recommend that, if the central bank is uncertain of the precise effect of an interest-rate cut on inflation, it should cut interest rates by less, even if this means letting inflation fall somewhat below target. This recommendation, however, abstracts from the fact that inflation also depends on the private sector’s expectations of inflation, a dimension that Brainard’s original set-up does not incorporate. The central bank takes these inflation expectations as given when it acts under discretion, but if the private sector foresees that the central bank will attenuate its policy response, it forms lower inflation expectations. This pushes inflation further down, and forces the central bank to decrease rates further. The central bank easily ends up decreasing rates by as much as it is initially reluctant to do, but with an inflation rate further below target than if it had not been concerned about uncertainty.

We give the name cautiousness bias to this perverse incentive that turns the central bank’s concerns over uncertainty against its own interests. The terminology is in direct reference to the inflation bias expounded by Kydland and Prescott (1977) and Barro and Gordon (1983a,b). Like the inflation bias, the cautiousness bias is a feature of policy under discretion: it arises because the central bank fails to internalize the effect of its policy on inflation expectations. Contrary to the inflation bias however, it does not arise from a desire by the central bank to set output above its natural level. It does not even require the central bank to care about stabilizing output, and applies equally to a central bank that has a single mandate to stabilize inflation only.

We study the cautiousness bias under various specifications of the Phillips curve relationship between output and inflation. In a New-Classical Phillips curve setup, we show that in response to shocks foreseen by the private sector, a cautious central bank ends up moving real rates by exactly as much as a central bank that disregards concerns over uncertainty would. However, despite ending up moving real rates by the same amount as a central bank that disregards concerns over uncertainty (which is also the optimal policy under commitment), a cautious central banker suffers greater volatility in inflation. In the spirit of Rogoff (1985)’s solution to the inflation bias, we show that society would be better-off appointing a central banker who discounts concerns over uncertainty relative to society, even if this means responding to unforeseen shocks too aggressively.

The New-Classical Phillips curve provides a simple exposition of the cautiousness bias, but abstract from modeling the dynamics in the interplay between interest rate decisions and the response of inflation expectations. Hence we study the dynamics induced by the cautiousness bias under the Sticky-Information Phillips curve of Mankiw and Reis (2002). With the Sticky- Information Phillips curve, the private sector only gradually incorporates new information into its inflation expectations. As a result, when a negative shock hits inflation expectations move little at first, and the central bank is able to attenuate the decrease in interest rates. But as the private sector gradually realizes the resulting fall in inflation, inflation is pushed down further, forcing the central back to decrease rates further, ultimately by as much as if it had not been willing to attenuate policy. We also show that the cautiousness bias applies equally to the forward-looking New-Keynesian Phillips curve (NKPC), which remains the most commonly used Phillips curve in economic modeling.