Post No. 390. In the face of geopolitical uncertainty, direct investments (DI) in strategic sectors are coming under increased scrutiny. This blog post proposes a mapping of inward DI in strategic French sectors linked to national security. In line with the European Commission’s recent recommendation, it also analyses critical French outward DI that could be subject to screening in the future.

Chart 1: Geographical and sectoral breakdown of France’s inward DI in 2023 (% of sector total)

Note: In 2023, more than 90% of DI in French quantum technologies was from the United States. Inward DI calculated using the 2nd method proposed below.

Foreign direct investment in strategic sectors is coming under increased scrutiny

In a context marked by public health and geopolitical crises, most advanced economies have recently strengthened or implemented foreign investment screening mechanisms for reasons of national security (Bencivelli et al., 2023). The EU in particular has introduced a harmonised framework under a 2019 regulation. These mechanisms allow national authorities to vet investments in sectors deemed strategic, or from investors linked to third-country governments. The investments can be completely blocked, or authorised with or without conditions.

In France, the screening framework is the responsibility of the Ministry of the Economy and Finance and has been substantially reinforced in recent years. In 2020, for example, the threshold above which non-European equity investment projects in French listed companies are subject to screening was lowered to 10% of capital. The list of critical activities has also been expanded: it was initially limited to defence and security activities, but now includes critical infrastructure (physical and electronic), critical technologies (quantum technologies, etc.), food security, media, and technology essential for the energy transition. On average, 320 approval requests for inward foreign direct investments (FDI) in these sectors were submitted annually to the Treasury between 2021 and 2023, accounting for nearly 20% of all projects identified by Business France (2024).

However, only a share of these – just over 10% – were deemed likely to pose a national security threat by the Treasury, and therefore subject to heightened controls.

It should be noted that this screening, which is proportionate and in the interests of national security, is not incompatible with a policy of attracting FDI for French industries of the future, such as electric battery factories (Business France, 2024).

Between 9% and 25% of FDI stocks in France can be deemed strategic

Given the confidentiality of screening procedures for FDI in France, it is difficult to estimate the amount of stocks. We propose two methods for quantifying inward investments liable to be considered critical, which gives us an estimate range. The upper bound is calculated by taking into account all sectors defined as strategic under French legislation. However, a second, more granular approach is needed to avoid overestimation, as a formal sectoral classification covers more firms than are actually identified as critical by the French authorities.

We therefore estimate a lower bound using a smaller list of firms operating in strategic sectors (defence, artificial intelligence, biotechnologies, semiconductors, quantum technologies, etc.), identified manually and using specialised databases (Refinitiv for financial and market data and Crunchbase for data on start-ups and investment). We also compile a list of firms in which the French state holds a stake and which are therefore likely to be subject to screening. We then match these two lists with the corresponding DI data compiled by the Banque de France. Whereas the legislation only applies to new FDI flows, our estimates take into account retroactive stocks (for example, we include all stocks of DI in defence in 2023, even though some of the flows generating these stocks date from before this period).

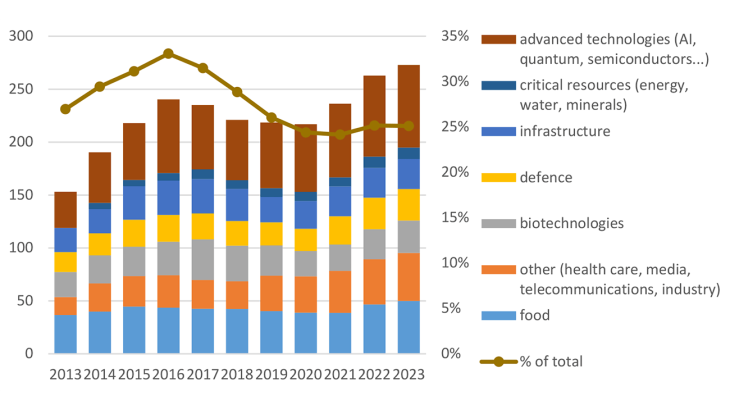

According to our upper estimates, in 2023, 25% of the stock of inward DI (excluding intragroup loans) was in an activity classified as critical under French law (see Chart 2). This large share is consistent with the high number of approval requests submitted each year to French authorities. The main ultimate investing countries in these sectors (i.e. where the economic decision-making centre is located, irrespective of any intermediate countries) were EU countries (13% of total stocks), notably Germany (2%), and the United States (5%). As a proportion of total DI stocks, investments in strategic sectors have declined over the past decade (they reached 33% of total stocks in 2016), due notably to the change in US DI in France. While the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (2018) – which encourages the repatriation of earnings held in US firms’ foreign subsidiaries – does not appear to have a had major impact on US DI in France in general (Banque de France, 2024), its implementation does coincide with a sharp drop in US DI stocks in strategic sectors – although this is offset to an extent by a concomitant rise in non-strategic DI stocks. This trend also coincides with a global reconfiguration of DI flows prompted by geopolitical considerations, especially in sectors where there is a high risk of “weaponisation” of economic relations (Alcidi et al., 2024).

Chart 2: Stock of inward DI in critical sectors calculated using 1st method (EUR billions and % of total)

Note: Upper end of estimate range (1st method). DI stocks include only share capital and reinvested earnings. Intragroup loans are excluded as they are primarily for tax purposes.

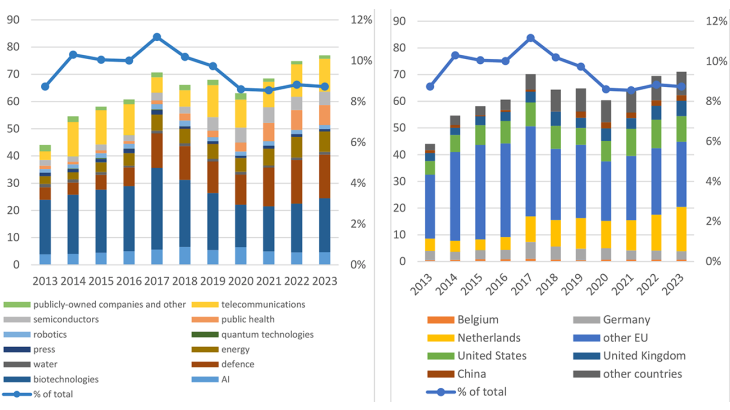

According to our lower estimates, using the granular method, in 2023, 8.7% of total FDI stocks in France were in critical firms (see Chart 3), representing a decline since 2016 (11%), as in the case of our upper estimate. This second method also confirms the geographical breakdown of DI found using the first method. However, it also shows that foreign investors appear to specialise in certain sectors (see Chart 1). Dutch firms, for example, were big investors in French defence and state-owned companies (public transport, etc.), reflecting the industrial alliances between large groups in the two countries. Moreover, the United States accounted for the majority of DI in quantum technologies, and China (including Hong Kong and Macau) accounted for 40% of DI in semiconductors, which is in line with the two countries’ respective sectoral specialisation.

Chart 3: Stock of inward DI calculated using 2nd method, by sector and by ultimate controlling country (EUR billions and % of total)

Note: Lower end of estimate range (2nd method). In 2023, DI in biotechnologies amounted to EUR 20 billion. Ultimate controlling country: country where the economic decision-making is located, excluding intermediation, as opposed to immediate counterparty country, which can only be an intermediary.

Outward investment screening would only apply to a limited number of activities

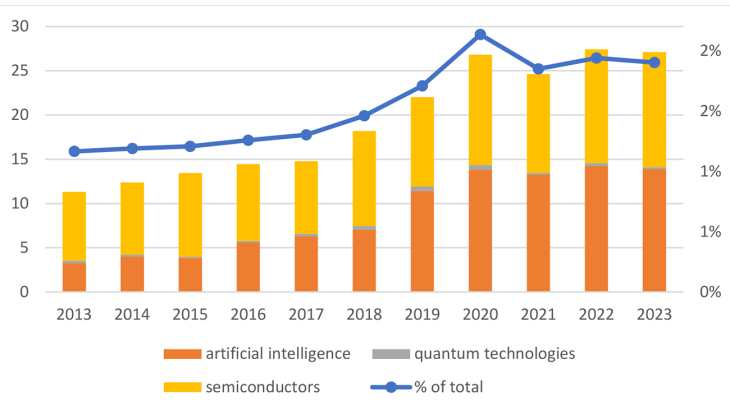

National and European authorities have recently turned their attention to the risk of technology transfer linked to outward DI, in addition to inward DI. In January 2025, the United States introduced a screening mechanism for US outward DI in Chinese artificial intelligence, quantum technologies and semiconductors (including in Hong Kong and Macau). In Europe, following on from its January 2024 White Paper proposing the screening of outward DI, the European Commission published a recommendation on 15 January 2025 calling on Member States to review outbound investments in three sectors: artificial intelligence, quantum technologies and semiconductors.

If implemented in France, this screening would apply to just 1.9% of French outward DI stocks in 2023 (see Chart 4). Of the three targeted sectors, French firms mainly invested in artificial intelligence and semiconductors (1.0% and 0.9% respectively of total stocks), and primarily in the United States and EU (1.4% and 0.3% of stocks respectively). Investments in countries that are not traditional allies remain low, although this still poses a risk of critical technology transfer. In 2023, the ten countries most geopolitically distant from France (according to the geopolitical distance indicator of Bailey et al., 2017) accounted for just 3.1% of the total stock of French outward FDI. Moreover, only 0.02% of stocks were invested in the three strategic sectors identified by the Commission. Although the risk of transfer of critical French technologies is not directly proportional to the size of DI stocks – a limited but highly sensitive leakage could generate major risks – France’s exposure remains low in volume terms, as confirmed by Velliet (2024) using another method to identify foreign financing of critical technologies in China.

Chart 4: Stock of French DI in the rest of the world in three critical sectors (EUR billions and % of total)

Note: Stock of French DI in the three sectors identified by the Commission, by immediate counterparty (country directly receiving the DI).

Download the full publication

Updated on the 17th of February 2025