Since its inception, the goal of the G7 has been to provide a coordinated response to global economic problems

The first informal meetings between the finance ministers of the United States, Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Japan were organised in the early 1970s. The aim was to deal with the crisis of the international monetary system following the collapse of Bretton Woods. The first summit of the Heads of State, in which Italy also participated, was organised in France in 1976. Canada also joined in that year, and the group became the “G7” or Group of Seven. After the fall of the USSR, the G7 invited Russia to join in 1997 and became the G8, but Russia’s membership was suspended owing to its unilateral annexation of Crimea.

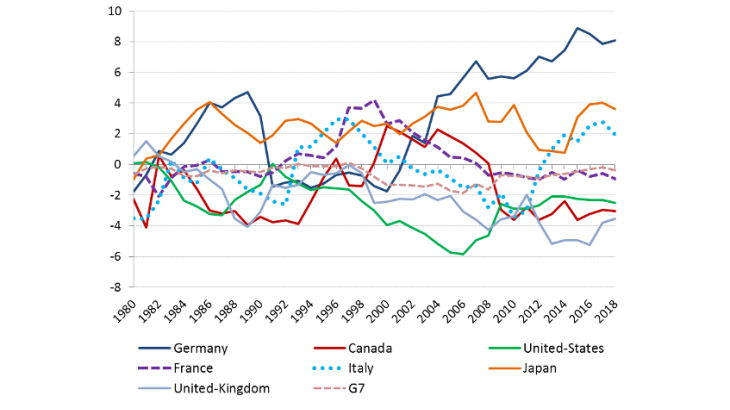

Monitoring the functioning of the exchange rate system has been and remains one of the key areas of action of the G7. With the Plaza Accord in 1985 and the Louvre Accord in 1987, the G7 became a forum for consultation prior to any coordinated interventions in foreign exchange markets. The G7 has reaffirmed its commitment to market-determined exchange rates and economic policies that do not target exchange rates, as evidenced by communiques adopted following its summits.

The G7’s scope of action has gradually broadened to include new areas such as development, the fight against terrorism, labour, health, agriculture, security, and climate change. Examples of this include the creation of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which was set up to combat money laundering and terrorist financing, and the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, launched in 1996 at the G7 Summit in Lyon, which provides conditional debt relief to allow such countries to achieve sustainable levels of external debt.

While the weight of the G7 in the global economy remains significant, it is declining continually

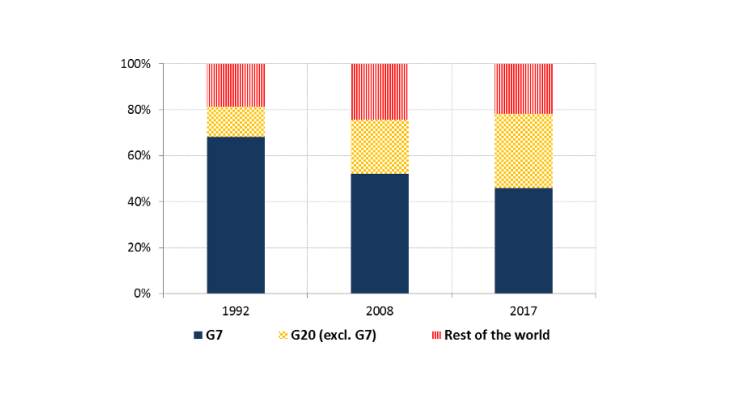

Since the 1980s, the G7’s weight in the global economy has been shrinking with the rise of emerging countries. In 2017, G7 member countries’ share in global GDP stood at 46%, against 68% in 1992 (Chart 1). Moreover, their share of the global population remained stable at around 10-12% over the same period. Some studies estimate that their share in global GDP could even fall to 20% by 2050. Moreover, emerging countries have become key players in globalisation: according to IMF data, emerging countries’ share in global trade rose from 22.8% in 1997 to 36.5% in 2017. Regional multilateralism has also grown, notably in the area of economic policy coordination as illustrated by the development of Regional Financial Arrangements in Europe and Asia. Against this backdrop, the G7 can no longer single-handedly provide responses, but it can propose responses.

The leadership role of the G20 during the global financial crisis of 2008 forced the G7 to adapt, though without abandoning its primary vocation of consultation and coordination in a smaller and more homogeneous committee. The G7 can play the role of antechamber to the G20 for discussions on new subjects or drawing up proposals. Therefore, alongside the G20, the G7 remains a tried and tested organisation for cooperation and dialogue among the main Western democracies (and Japan), which enjoy free market economies and floating and convertible currencies. The G7 can also count on the expertise and institutional memory of several decades of economic cooperation.

G7 countries are facing common challenges for which multilateral solutions are necessary

Since the global financial crisis, most G7 countries have implemented expansionary fiscal policies and accommodative monetary policies. They have also adopted structural policies that have often not been ambitious enough to meet the challenges of an ageing population, the slowdown in productivity, and climate change. While these economic policies have helped to resolve the crisis, they have reduced the ability of G7 countries to conduct countercyclical policies and thus deal with a new crisis.

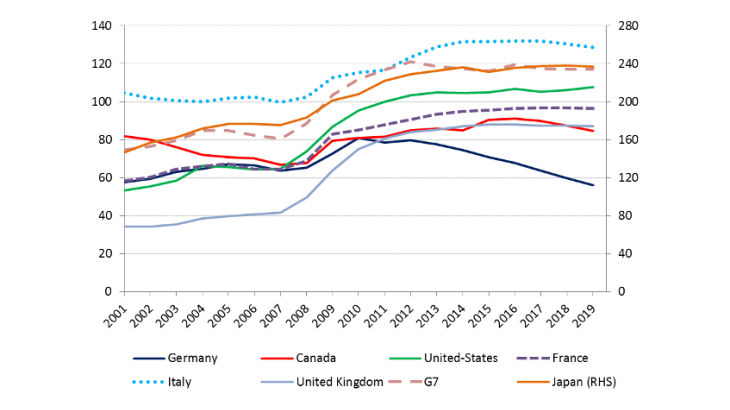

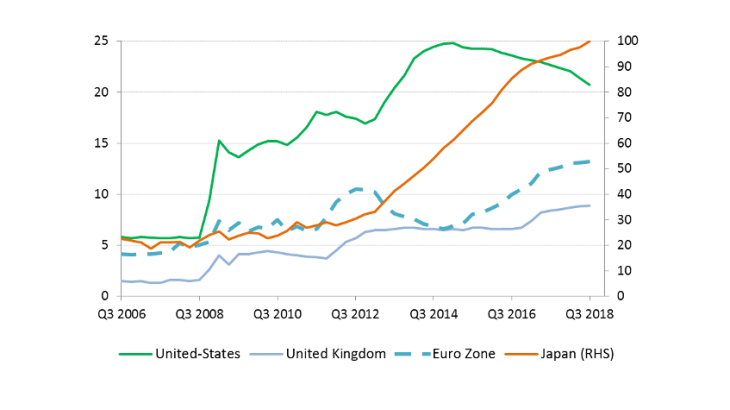

For instance, fiscal policy is constrained by elevated debt levels (Chart 2) which, with only one exception, remained very high during the last cyclical upswing; this constraint is compounded by structural developments such as the ageing population. Monetary policy remains limited by the very low level of interest rates and the expansion of central bank balance sheets (Chart 3). In this environment, the temptation by some countries to use the exchange rate to create some space for countercyclical policies is great. The G7 plays a key role in enforcing the commitment of countries issuing the main international currencies not to target the exchange rate in their economic policy and thus in preventing the risk of a currency war.