- Home

- Publications and statistics

- Publications

- External wealth (or debt) as drivers of ...

Post n°69. Reducing current account imbalances is often equated with curbing excessive exports or imports. However, legacies of the past can develop their own dynamics due to accruing income flows. Indeed, in some countries that have accumulated large foreign liabilities, current account adjustment has been impeded by large negative income flows despite substantial improvements in the trade balance.

Source: IMF BoPS

Current account imbalances, in particular deficits, imply important risks for external debt sustainability and the likelihood of sudden stops in capital inflows (see the discussion in Obstfeld, 2012). Whereas even large current account deficits can reflect optimal resource allocation across countries and time, experience has shown that imbalances are often an indicator of subsequent crises and sudden stops, thus motivating the call for a reduction of current account imbalances.

Ever larger stock imbalances despite reduced flow imbalances…

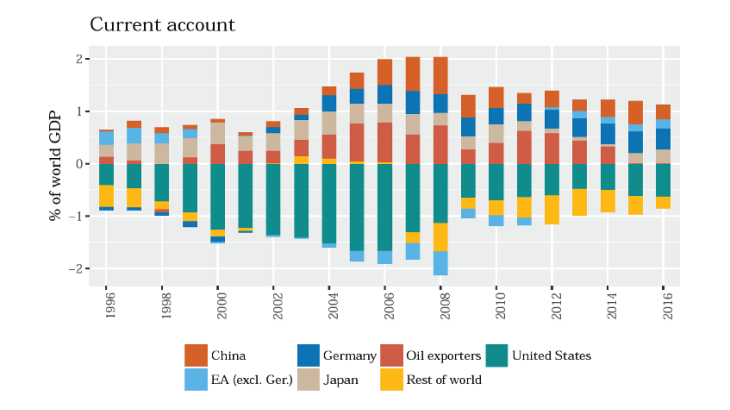

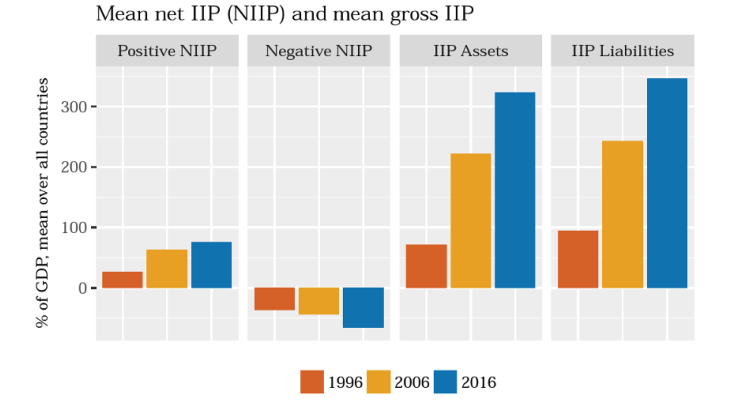

Prior to the 2008-2009 financial crisis, current account imbalances widened (see Figure 1), leading to substantial net imbalances that were accompanied by a rapid expansion of gross external positions. Subsequently, current account imbalances were reduced, but it is important to notice that this reduction was not sufficient to reverse any of the large external positions that were accumulated prior to the crisis. As shown in Figure 2, gross positions are now 3 to 4 times larger than 20 years ago, attaining on average a level of over 300% of GDP. Net positions are considerably smaller, but have widened by a factor of 2 with respect to their level in 1996.

Source: IMF BoPS. Notes: IIPs are displayed as a mean across all countries for which data are available at the respective years. The first two panels show the respective data for creditor and debtor countries.

While current account imbalances ceased to expand with the onset of the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, the persistence of the levels observed from 2009 onwards implies that holdings of external assets and liabilities continue to increase for a large number of countries.

To what extent does the continuous accumulation of external stocks matter for the dynamics of the current account itself? The current account is the sum of the trade balance, net secondary income (which is mainly personal transfers and payments between governments) and net primary income. The latter, defined as the difference between income received (from asset holdings) and payable (to holders of one’s liabilities), is a direct result of accumulated stocks and takes the form of interest and dividend payments. As long as the size and/or composition of the stock of external assets differ from that of liabilities, the gross income flows generated by these stocks will not be the same. On the one hand, net creditors usually receive more income from their assets than they have to pay on their liabilities. All else equal, this leads to further current account surpluses and thus further wealth accumulation. On the other hand, differences in the asset-liability composition (i.e. by investing in high-yielding equity securities and being indebted in low-yielding debt securities) or the return within one asset class can lead to important imbalances in net primary income.

Source: IMF BoPS.

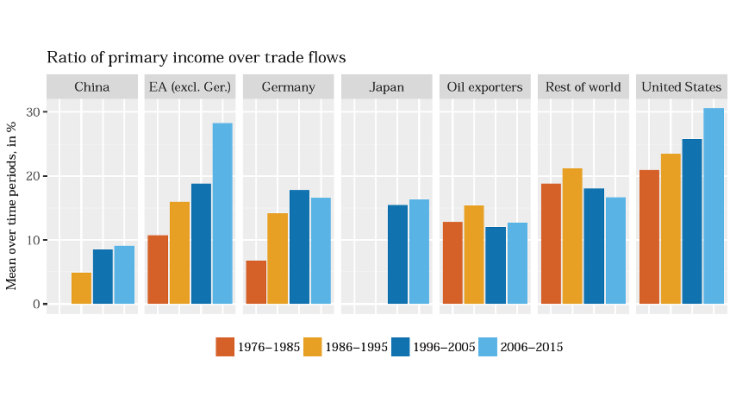

Notes: The mean value of the ratio is taken with respect to the time periods indicated. Data for China are only available for 1982 onwards and data for Japan are only available from 1996 onwards

… implying an increasingly large weight of income flows in the current account

In Figure 3, the ratio of primary income flows over trade flows is displayed for different time periods. It is calculated as the sum of income receivable and payable, divided by the sum of exports and imports. Over the last decades, this ratio has continuously increased reaching 20%-30% for some euro area economies or the United States. (A similar point is also made in Forbes et al., 2017.) While the Great Financial Crisis and low interest rates have reduced this ratio to some extent in recent years, income flows remain important for current account dynamics. This is not surprising given that the Great Financial Crisis put a halt to the expansion of gross positions, but has not led to a fundamental reversal.

In a large number of advanced economies, a decomposition of primary income by type of financial instrument shows that these income flows are to a large extent driven by large FDI yields. Curcuru et al., 2013 show for the case of the United States that the asset-liability differential for FDI is to a large extent driven by taxes. On the one hand, earnings on external assets are reported before taxes while non-resident earnings on US assets are reported after taxes. On the other hand, profit shifting results in firms reporting their earnings abroad instead of at home. A similar point is also made by Blanchard and Acalin, 2016 who show that FDI flows are driven by corporate tax rates. It has also been shown that transfer pricing, i.e. the price-setting of cross-border transactions between affiliates of the same multinational group, decreases the value of net exports. For example, Vicard (2015) estimates for the case of France that profit shifting through the use of transfer prices contributed to a worsening of the trade deficit by 9.6% in 2008 (while boosting FDI income). Though these accounting strategies do not change the overall current account balance (as the sum of the trade balance and net FDI income remain the same), they imply that the investment income balance is even more important for driving current account dynamics.

Should one be worried?

Primary income from past investment might play an ever important role in current account balances, but this should not be a reason to worry per se as these can have either a stabilising or destabilising impact, depending on whether they attenuate or reinforce trade imbalances and contribute to a widening or reduction of external positions. A prominent example is the case of the United States where positive net primary income flows have attenuated the effect of a large negative NIIP. For the case of China, the relative importance of trade and income balances has had a stabilising effect as well, though in the opposite direction: while the trade surplus has been largely positive, it has paid non-residents more on its external liabilities (high-yielding FDI) while receiving less on its external assets (mainly US government bonds with low yields). In some cases, however, the legacy of the past can represent a considerable drag on current policies that aim to reduce imbalances.

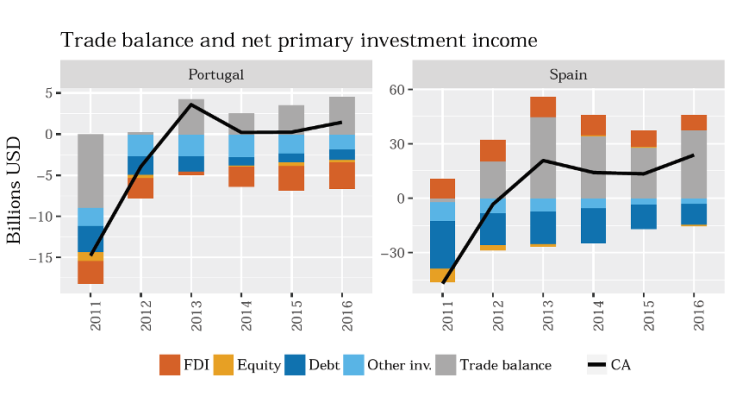

Source: IMF BoPS.

Notes: Primary income is decomposed into income from direct investment (FDI), portfolio investment income on equity and investment fund shares (Equity) and in the form of interest (Debt) and other investment income (Other inv.).

Consider the current account dynamics of Spain and Portugal in the past years as displayed in Figure 4. Despite substantial improvements in the trade balance, interest rate payments on debt instruments and other investment income (consisting mainly of bank credit) had a substantially negative impact on the current account balance, thus limiting these countries’ rebalancing efforts.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024