By Valentin Sayagh, student in the first year of preparation for administrative competitions at Sciences Po Paris and Wessim Jouini, student in Master 2 Economic analysis and policy at HEC.

2nd prize in the 2024 Eco Notepad blog competition

Batteries are a good example of the challenge posed by the fragmentation of the global economy to Europe's supply of raw materials for the transition. The EU has put in place a strategy to diversify supply through market mechanisms. This strategy is under threat from geopolitical forces and the ambitions of mining countries. Consequently, it needs to adapt.

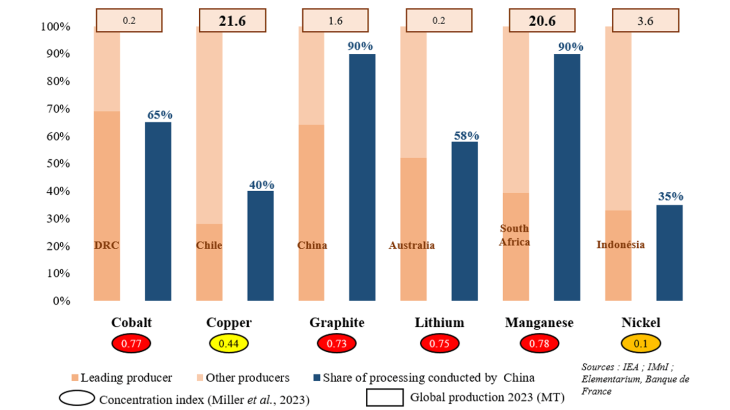

Chart 1 - Concentration of the mining and processing of six critical minerals

Energy transition industries depend on geographically concentrated “critical” raw materials

Securing supplies of certain key raw materials is crucial to the success of European industries involved in the energy transition. These raw materials are on the list of ”critical”’ materials drawn up in 2011 by the European Commission, which defines them as being both of economic importance to European industry and subject to supply risk due to low availability or high deposit concentration.

Some of these materials are of strategic importance due to their use in key transition technologies, both at present and in the foreseeable future. The use case of batteries illustrates the growing tensions around supply in a context of global trade fragmentation as a result of:

- the importance of the downstream automotive industry in Europe, a sector that generates 13.8 million direct and indirect jobs (6% of all jobs in the EU);

- the importance of transport in achieving the EU's net zero target by 2050 (24% of CO2 emissions, including 76% from road transport);

- the pioneering role of European regulation (or the “Brussels Effect”), particularly in this area, which could give European industry a comparative advantage on external markets if its production capacity allows it to do so;

- sovereignty issues relating to Europe’s autonomy in this area, and the resulting policies implemented (European Battery Alliance Important Projects of Common European Interest, Battery 2030+, etc.).

The six raw minerals on the Commission's list that are critical to the production of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles are mined in a small number of countries, known as “mining countries”, most of which are outside Europe

Energy transition industries depend on geographically concentrated “critical” raw materials

Securing supplies of certain key raw materials is crucial to the success of European industries involved in the energy transition. These raw materials are on the list of ”critical”’ materials drawn up in 2011 by the European Commission, which defines them as being both of economic importance to European industry and subject to supply risk due to low availability or high deposit concentration.

Some of these materials are of strategic importance due to their use in key transition technologies, both at present and in the foreseeable future. The use case of batteries illustrates the growing tensions around supply in a context of global trade fragmentation as a result of:

- the importance of the downstream automotive industry in Europe, a sector that generates 13.8 million direct and indirect jobs (6% of all jobs in the EU);

- the importance of transport in achieving the EU's net zero target by 2050 (24% of CO2 emissions, including 76% from road transport);

- the pioneering role of European regulation (or the “Brussels Effect”), particularly in this area, which could give European industry a comparative advantage on external markets if its production capacity allows it to do so;

- sovereignty issues relating to Europe’s autonomy in this area, and the resulting policies implemented (European Battery Alliance Important Projects of Common European Interest, Battery 2030+, etc.).

The six raw minerals on the Commission's list that are critical to the production of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles are mined in a small number of countries, known as “mining countries”, most of which are outside Europe

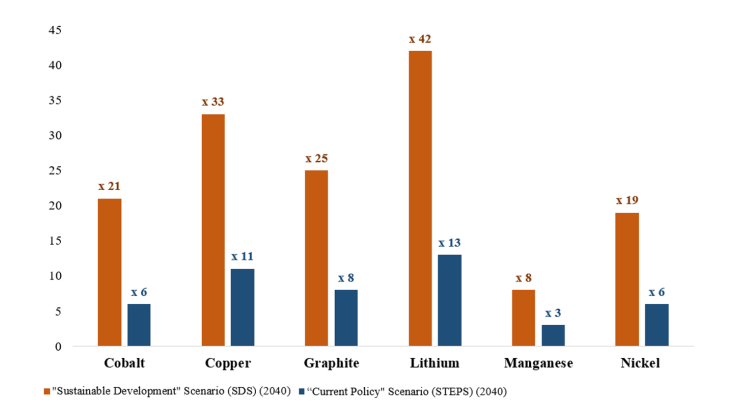

Chart 2: Increase in global demand for batteries between 2020 and 2040

Expectations of rising demand and concentrated supply are such that there is a risk of a processed metals shortage, which is exacerbating strategic rivalries. This means that importing countries need to devise an active strategy to secure supplies, particularly of copper, lithium and nickel, for which demand is set to increase the most, and to adapt to changes in mining countries' value chains.

Mining countries want to expand local processing and are now choosing their partners.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been a fragmentation and shortening of global value chains (Lachaux, 2023).

Moreover, geopolitical factors are impacting value chains, leading to a segmentation of the economy along the lines of “friend-shoring”.

The drive to secure supplies of raw materials is reflected in the establishment of long-term contracts between importing countries and their allied producers. In 2008, for instance, China signed a EUR 9 billion contract with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to mine copper and cobalt deposits in return for building infrastructure.

This geographical proximity enables these importing countries to guarantee supplies for their downstream industries and to become themselves exporters of refined raw materials, in order to take advantage of this, including from a geopolitical standpoint, with regard to Europe (Beaujeu et al, 2022).

Indeed, several countries have already introduced policies to limit exports of raw minerals, to promote domestic processing. Such policies have included assigning a predominant role to state-owned companies, such as the public-private partnership between the state-owned company Codelco and the private group SQM for the management of Chilean lithium. However, developing these processing industries partly requires foreign capital, which opens up the possibility of setting up joint ventures or production-sharing contracts.

For example, Indonesia, which is home to 42% of the world's nickel reserves, has made nickel processing a major focus of its industrial development, working with Chinese companies as part of the New Silk Road initiative. The same is true of Namibia and Zimbabwe (lithium), among other African countries, which both rely on international partnerships in which Europe is under represented (Reuilly, 2024).

Given the export restrictions imposed by mining countries, the EU must implement a two-tier policy in this area, in order to increase the share of batteries produced locally, which is currently limited to 7% of global production, compared with 76% in China (Citton, 2023).

Firstly, the aim is to encourage the signature of long-term contracts with mining countries to ensure that the metals are processed locally by European firms. Secondly, we need to increase the production capacity of the finished good (batteries) in Europe by investing in securing supplies from mining countries, where the first stages of local processing are now located (Giraud, 2024).

Europe's response is incomplete and overlooks partnerships with mining countries

To date, although the European Critical Raw Materials Act (CRM Act, 2024) constitutes an initial response (based on the three pillars of diversification, recycling and R&D), it is incomplete. Indeed, the CRM Act is based on a passive approach and market mechanisms. Supplies are secured by diversifying channels, with the main rule being that we must not be more than 65% dependent on a single country for each mineral.

However, such an approach overlooks (1) the geological limitations to this diversification, (2) demands from mining countries to partially process the raw materials (see above), and (3) the risk of the market approach being replaced by an approach based on long-term bilateral contracts (including the joint financing of mining, in a Chinese-style model).

For example, the Net Zero Industry Act (which sets the EU the target of meeting 40% of its critical metals technology needs by 2030) could be adjusted so that the quota also includes production financed by European capital in mining countries.

In addition, as recommended by the European Court of Auditors (Special Report 2023),

we need to adopt a strategy based on identifying relevant partners and integrating these partnerships with the European development policy. This could take the form of easier access to the European market (under the Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP+), extended until 2027) in exchange for European investment in local mining and processing infrastructures.

Moreover, the earmarking of funding from the European Union's Neighbourhood, Development Cooperation and International Cooperation Instrument (ENDCCI) would make it possible to promote the participation of partner countries in the joint financing of key infrastructure alongside the private sector, as part of the Global Gateway Strategy.

Lastly, as part of the European Battery Alliance, a mechanism for pooling and securing supplies could be put in place and supervised by the Commission, using long-term contracts negotiated at Alliance level.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 6th of December 2024