The International Energy Agency estimates the financing required to make the transition to a low-carbon economy at several hundred billion euro worldwide per year while the Institute for Climate Economics (I4CE) considers that France alone needs additional investment of between EUR 45 billion and EUR 75 billion per year. This requires a sustained effort from private players, particularly banks and insurers, given the key role they play as a source of financing in the French economy.

Both these sectors are directly exposed to some of the risks associated with climate change. Several recent publications by the Autorité de contrôle prudentiel et de résolution (ACPR – the French Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority) analyse the way in which banks and insurers integrate and manage climate-related risk and, for the insurance sector, the extent to which the provisions of France’s Energy Transition Law have been implemented.

We can draw four main conclusions from this work.

1. Significant progress has been made in terms of governance of risks associated with climate change. In addition to announcements that policies were in place to disinvest from heavy greenhouse gas (such as carbon dioxide) emitting sectors, overall, banks and insurers have adopted strategic guidelines that comply with the objectives of the Paris Climate Agreement. Some have procedures in place to regularly report information on their exposure to climate-related risks to their highest decision-making bodies. In this case, the risk associated with climate change is also integrated into the framework of standard financial risk management procedures. However, the progress observed is mixed within the two sectors and has not generally been rolled out to business lines’ operational levels.

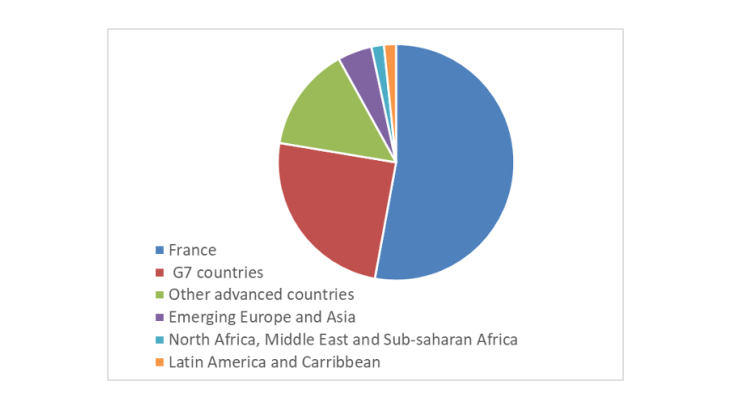

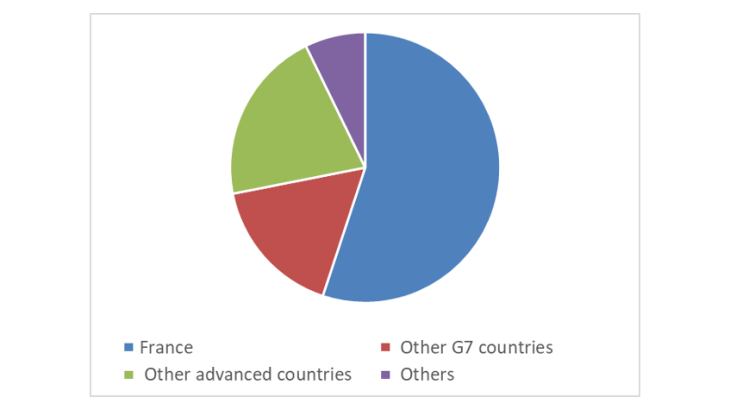

2. Little progress has been made in terms of taking account of physical risks, which measure the direct impact of climate change on people and property (through droughts, floods, extreme weather events, etc.), and to which, admittedly, French banks and insurers are relatively little exposed. By comparing the location of exposures presented above with those taken from the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) or academic studies such as that of Burke, Hsiang and Miguel (2015), we find that the exposures of French banks and insurers are generally located in areas considered not very vulnerable with regard to currently available climate change scenarios, and the majority are located in France, where there is an effective mechanism in place to take account of natural disasters.

In this area, we note that insurance organisations, beyond the risks to their balance sheet assets, have developed, for the needs of their business, extremely detailed measures to track the location of insured people and property. In the insurance sector, the risks associated with the increase in the frequency and cost of extreme weather events have direct consequences on the pricing of insurance policies, which could ultimately raise doubts as to the insurability of certain risks, with potential implications for public policies and financing costs (rise in risk premiums and devaluation of property acting as collateral).

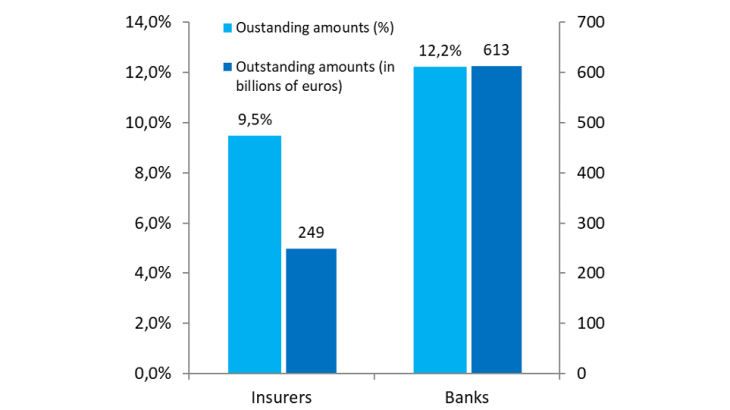

3. There is a growing recognition of transition risk, which measures the financial impact of a shift in the behaviour of economic and financial players in response to the implementation of energy efficiency policies or technological changes. This progress reflects the a priori significant exposure of French financial institutions to the most carbon-intensive sectors. With regard to banks, it is estimated that the 20 most carbon-intensive sectors accounted for 12.2% of net exposures to credit risk in 2017, down slightly compared with 2015, while, adopting the approach of Battiston et al. (2017), approximately 10% of French insurers’ investments were estimated to be in transition-risk sensitive sectors (fossil fuel, electricity or gas producers or consumers). The level of exposures appears extremely inconsistent within the two sectors.