Low-income countries are struggling to cope with a systemic crisis of unprecedented scale

The Covid-19 crisis has highlighted the vulnerabilities of LICs to global shocks, largely due to their low level of development. Health risks remain significant, while vaccination programmes have barely started and are still underfunded. The risks of slow or fragmented spreading as well as local outbreaks appear to be higher than in advanced countries, due to the shortcomings of health systems. They add, due to possible cross-epidemic effects, to the heavy epidemiological burden, especially for the most vulnerable populations.

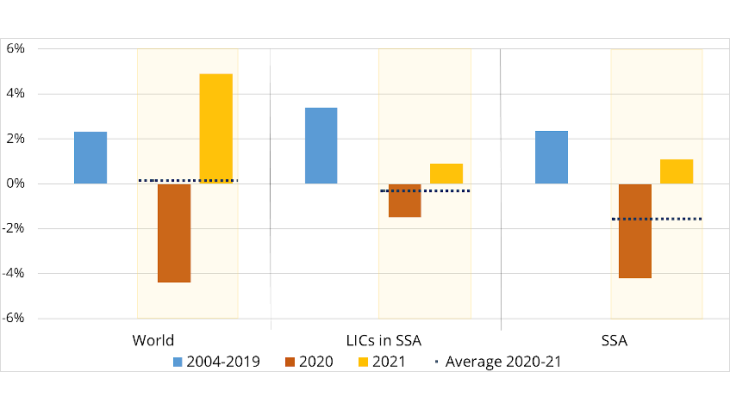

The long-term socio-economic consequences are expected to be particularly severe in developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Even though the economic recession has been more subdued on average in LICs, the crisis is causing delays in growth, making it difficult to achieve sustainable development goals. According to the IMF's April 2021 forecast, per capita GDP is set to fall by 1.6% in SSA in 2020-21, while it is expected to rise in the rest of the world (see Chart 1). This divergence can be partly explained by low fiscal (50% of LICs are at high risk of debt distress) and monetary leeway, due to external constraints. In addition to the initial rise in poverty, longer-term effects on human development are anticipated due to increased malnutrition, worsening access to health systems, and loss of education due to school closures, leading to the worsening of poverty traps.

In view of the risks of long-term damage to LICs, there is a case for rapidly strengthening the IMF's financial safety net. Its aim is to meet the sharp escalation in their financial needs (USD 450 billion by 2025 according to the IMF), generated by a crisis of unprecedented magnitude and of systemic nature. It can also, in the longer term, contribute to reducing the vulnerability of LICs caused by climate change, among which the expected rise in epidemic risks is only one aspect.

An enhanced but still insufficient financial safety net for LICs

A financial safety net centred on LICs was developed by the IMF in the wake of the 1997 and 2009 crises. In 1999, the IMF's Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF) was replaced by the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF), at a subsidised rate (currently 0%). Unlike the ESAF, whose conditionality was based primarily on stabilisation and structural adjustment objectives, the PRGF is based on economic and social development objectives and poverty reduction strategies in coordination with the multilateral development banks. These programmes have also been associated with major debt restructurings under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative. Financed by voluntary contributions, loans and grants from member countries, the PRGF has been significantly strengthened since 2009, both financially, notably through the reallocation of SDRs from rich countries including France, and operationally through a reform of its concessional financing facilities.

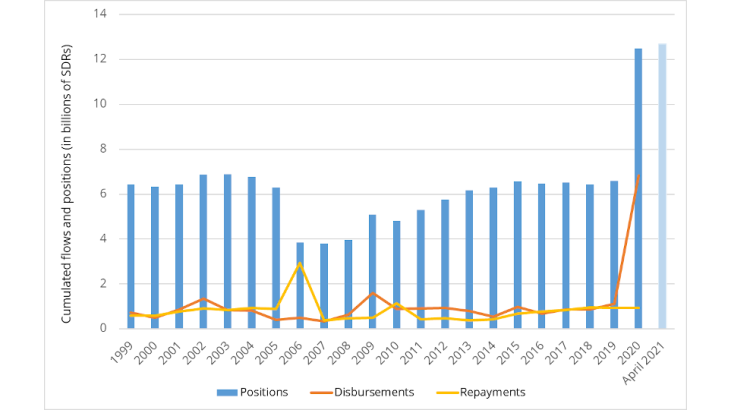

The Covid-19 crisis has shown the need for ambitious reform, including a scaling up of the IMF financial safety net. Thanks in part to the existence of a rapid credit facility and the temporary increase in access ceilings, the IMF was able to respond quickly to the crisis, affecting more than two-thirds of PRGF-eligible countries, with a six-fold increase in new commitments in 2020, reaching SDR 12.5 billion outstanding at the end of December (Chart 2). This includes the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) whereby bilateral creditors are suspending debt service payments from the poorest countries until the end of 2021. However, this effort has been insufficient to meet the external financing needs of LICs, notably because the latter are skyrocketing and other concessional financing, notably bilateral, is more constrained.