- Home

- Publications et statistiques

- Publications

- The blue economy in Overseas France: cha...

Post n°106. The blue economy encompasses all economic activities related to oceans, seas and coasts. Thanks to its overseas territories, France has the second largest marine zone in the world. World population growth and trade contribute to the development of the blue economy, which can be a driver of sustainable and innovative growth for Overseas France provided certain structural constraints are overcome.

(*) For further details of the sectors covered, see l’économie bleue dans l’Outre-mer (“The blue economy in Overseas France”, in French only).

(**) ISPF: Institut de la statistique de Polynésie française (statistical office for French Polynesia); ISEE: Institut de la statistique et des études économiques de la Nouvelle-Calédonie (statistical and economic research office for New Caledonia); Acoss: Agence centrale des organismes de sécurité sociale (the French social security treasury agency).

The blue economy covers the primary sector (fishing, aquaculture), the secondary sector (processing of fishery products, ship and port building, energy generation, undersea cables) and the tertiary sector (seafood marketing, transport of passengers and cargo, nautical services, port activities, coastal development, marine R&D, etc.). It also includes tourism to a greater or lesser extent depending on the scope used.

According to the OECD, the contribution of marine activities to global value added could double by 2030. Although this sector is already well established in Overseas France, it struggles with supply constraints and fierce, multifaceted competition, and at the same time has to contend with diverse environmental challenges. Provided these difficulties are overcome, the blue economy can become a driver of sustainable growth for Overseas France.

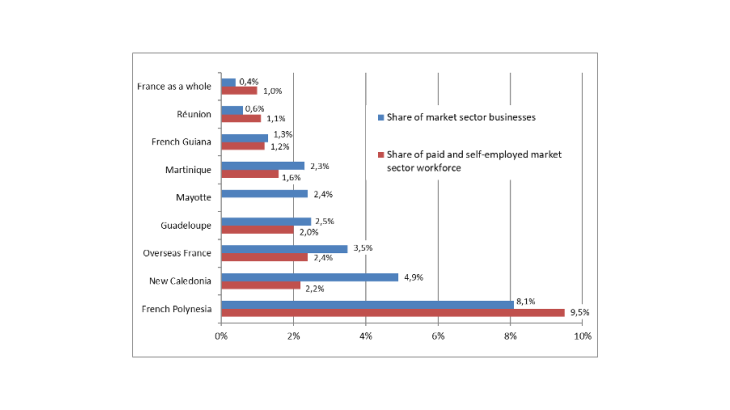

The blue economy in Overseas France: 2.4% of market sector employment and 3.5% of businesses

Despite the extensive coastlines and abundant islands of Overseas France, the importance of the blue economy there, although greater than for France as a whole (see Chart 1), is still limited: 8,800 firms and 12,500 jobs (depending on the scope used) with significant variations between territories. Most firms are involved in fishing, aquaculture and the processing and marketing sectors: almost 70% in Martinique and French Guiana and up to 89% in French Polynesia.

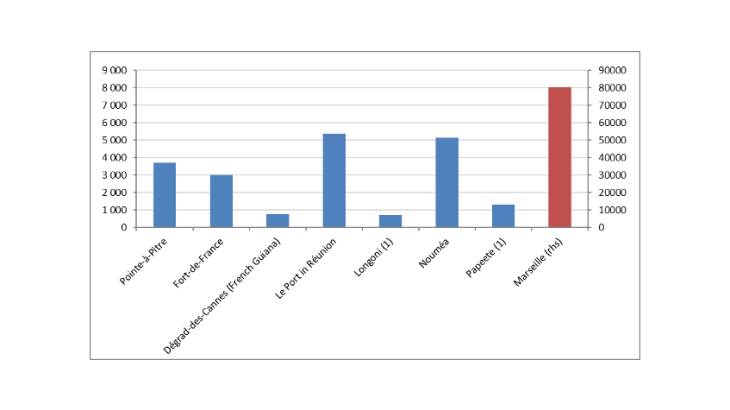

As the world’s leading method of goods transportation, shipping by sea also provides a fundamental support to the overseas economies, and, furthermore, develops in line with growth in global trade. In 2017, Le Port in Réunion, Pointe-à-Pitre in Guadeloupe, Fort-de-France in Martinique, and Nouméa in New Caledonia were classed among France’s 15 busiest ports in terms of cargo traffic (according to Ministry of Transport and ISEE figures). Le Port is the busiest French port in Overseas France (see Chart 2) and is on its way to becoming a regional hub in the Indian Ocean thanks to three regular maritime services from Europe and eight from Asia. Nouméa is already established as Oceania’s second most important transshipment hub after Fiji.

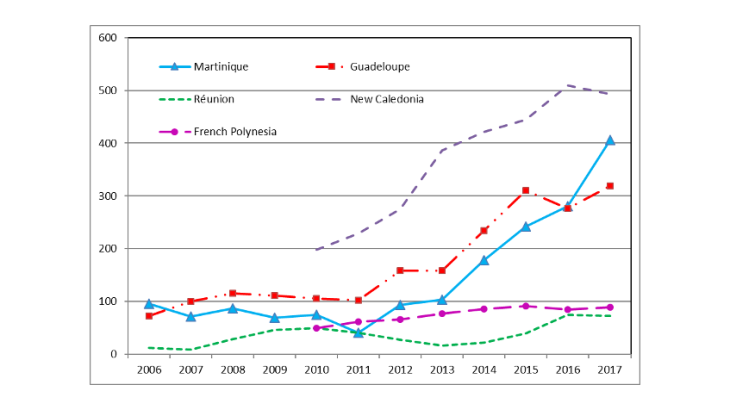

The cruise industry has also enjoyed significant growth in the Pacific overseas collectivities since the beginning of the 2010s and has rebounded in the overseas departments since 2011 (see Chart 3). This notably reflects renewed confidence among professionals after the industrial action of 2009 and the efforts made to better welcome passengers (providing foreign language training to local shopkeepers, for example). The number of passengers handled in Réunion more than tripled between 2014 and 2016 thanks to an increase in the number of ports of call (35 in 2017 compared with 19 in 2011, according to the Réunion Port Authority). Numbers are up in New Caledonia too, which also benefits from new ocean liner routes. Cruise passenger flows there have increased on average by 18% per year since 2010 (compared with a 4.7% increase worldwide).

The expansion in these sectors in Overseas France is the result of substantial investment in the local port infrastructures against a backdrop of strong global growth in the transport of passengers and cargo. One example is the EUR 17 million extension to the ocean freight platform in Fort-de-France completed in 2016. Thanks to these types of investment, ports are being remodelled to accommodate significantly larger standard-sized container ships and to improve the handing of cruise ships and the services offered.

Poor competitiveness, a skills gap and environmental challenges are holding back the blue economy in Overseas France

The French overseas territories face particularly fierce regional competition in the sectors of maritime freight, blue tourism and aquaculture. Labour costs, the tax system and the quality of the service offering seem to be major determinants of regional competitiveness in these sectors and poorer positioning in one or more of these determinants may have contributed to slowing the development of the blue economy in Overseas France. For example, in 2016, Martinique and Guadeloupe handled only 1.8% of the flow of cruise passengers in the Caribbean, far behind the Bahamas’ 16% (Caribbean Tourism Organization Annual Statistical Report, 2017).

The fishing and aquaculture industries suffer more specifically from a skills gap. The lack of training for the fishing professions hinders the renewal of a workforce that is already ageing and dwindling as a result of the rundown condition of the fishing fleet and the industry’s unattractive working conditions. This shortage of training also penalises the aquaculture sector, as its technical sophistication, administrative constraints, health risks and climate-related challenges require specialised skills that restrict the entry of new producers.

Lastly, the overseas territories have to contend with environmental problems (pollution of coastal waters, decimation of plant and animal life) that cry out for a rethink of the overall development strategy for the marine economy. This is particularly the case in the fishing industry, which must face up to the decline in fish stocks that significantly limits growth potential in the medium and long term.

The future of the blue economy in Overseas France: high value added niche sectors?

New avenues for development in the field of marine biotechnology are being studied in New Caledonia and Réunion. Renewable and innovative marine energy technologies, such as Sea Water Air Conditioning (SWAC) in French Polynesia and Réunion, are also being tested. The production of industrial microalgae, already developed in Réunion, could provide a basis for the renewal of the aquaculture sector. The telecommunications sector (installation of undersea fibre-optic cables) also represents a vector of development.

In February 2017, in the wake of the European Union’s 2012 “Blue Growth” report, France adopted a National Strategy for the Sea and Coast, which outlined French economic and ecological ambitions and set out four specific objectives: the ecological transition, the development of the blue economy, the good environmental status of the marine environment and the preservation of the coastline, and the extension of France’s influence. This strategy should be rolled out in Overseas France during the first half of 2019, with the aim of making the blue economy a driver of sustainable growth. To be successful, local productive systems will have to be modernised.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024