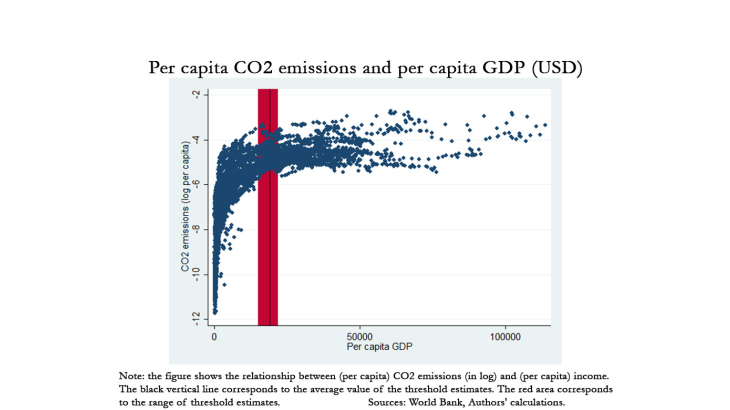

Emissions of pollutants tend to be procyclical as they generally increase with economic growth. At the same time, the intensity emissions along the development path is not linear, as it is relatively higher for medium-income countries compared to both low-income and high-income countries, giving rise to a possible inverted U-curve in the relationship between economic development and environmental degradation.

Government policy has a role to play in mitigating the environmental consequences of growth. First, a good environmental policy could advance the turning point and lower the size of the maximum emissions when reaching this threshold development level. Second, active environmental policies are justified even at early stages of development, given that the accumulation of environmental damages may be far greater than the present value of higher future income. Third, while environmental degradation depends on higher growth at early stages of development, the extent of the procyclicality of emissions largely depends on the efficiency of markets and policies. Against this background, the quality of institutions may influence the procyclicality of pollution and reduce the environmental externalities of economic growth.

This empirical study focuses on the procyclicality of emissions and the role of institutions in moderating them. The originality of the work is threefold. First, it is based on an up-to-date database including a very large number of countries over a long period (142 countries over 1960-2017), allowing to account for the heterogeneity in levels and speeds of economic development as well as different qualities in institutional settings. Second, it provides an empirical evidence on the role of institutions in moderating the environmental externalities of economic growth, supporting recent theoretical work on the need for governments to design environmental policy that responds to business cycle conditions. Third, the empirical approach is designed to tackle all critical issues usually encountered when testing empirically the pollution-income nexus by adopting a non-linear empirical approach while accounting for the various criticisms made to previous empirical work. More specifically, the approach is immune to issues related to the integration order of variables and accounts for endogeneity issues, bi-directional causality, heterogeneity across countries and cross-sectional dependence.

The empirical results first confirm the presence of threshold effects in the relationship between pollution and growth. In the case of CO2 emissions, we find an inflexion point in the average growth of emissions for countries whose per capita income is greater than U.S.$ 18,500. Our results also confirm a significant degree of procyclicality of emissions. For one percentage point increase in real per capita GDP growth, the emissions of CO2 are higher by 0.5 percentage point. We then test for the role of institutional quality in the relationship between pollution and growth. Our empirical analysis shows that countries with better institutional quality experience inflexion or turning points at lower per capita income. Moreover, once such threshold development levels are passed, CO2 emission growth is much lower for countries with high-quality institutions. The procyclicality of emissions is also reduced for countries with the best institutional scores. By reducing the procyclicality of pollution, the improvement in institutional quality is therefore a key factor in attenuating the environmental externalities of economic growth.