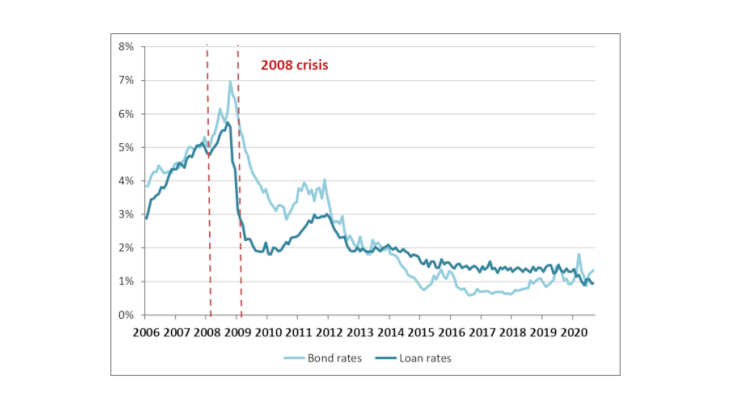

Note: Increase in the cost of financing of French companies through bank and bond debt during the 2008 financial crisis, as shown between the red dotted lines.

The current Covid-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented drop in activity and income for businesses. One of the measures taken in France in response to the crisis was the implementation of a State-guaranteed loan programme (SGL). It aims at securing companies’ financing needs by rolling over maturing debts and extending new loans needed to absorb the liquidity shock. This programme has been used by both small and medium-sized enterprises and large groups: intermediate-sized and large enterprises account for around a quarter of the amounts lent (at end-August). Such a measure is crucial in order, on the one hand, to enable companies to honour their short-term payments and, on the other, to preserve productive capacity by preventing that long-term strategic expenses such as investment be used as an adjustment variable, which would jeopardise the recovery phase.

Financing constraints, i.e. the impossibility of rolling over their debt in times of crisis, can lead (large) enterprises to cut back heavily on capital expenditure, as the 2008 financial crisis shows.

Investment and cost of financing in times of crisis

A company decides to invest in a project if its expected profits exceed its costs. The investment decision is therefore based on two distinct elements: on the one hand, an estimate of the future earnings streams from this investment ("demand" factor) and, on the other, an assessment of its financing cost ("supply" factor). The conditions for accessing external financing (credit or securities issuance) are thus a key determinant of the investment decision and ultimately of the investment dynamics at the macroeconomic level (Carluccio et al., 2018).

Understanding the extent to which investment fluctuations are linked to demand factors (such as growth prospects and investment opportunities) or supply factors (such as financing that is too expensive or too scarce) is a key issue because the implications in terms of economic policy are very different, especially in times of crisis when access to credit becomes more difficult.

How to measure the reaction of investment to a financing supply shock?

Isolating the effect of a decline in the supply of financing on companies’ investment behaviour is a delicate exercise. Indeed, empirical analysis comes up against two main difficulties.

1. We need to identify a "shock" that is not related to any change in the risk of borrowing companies, or to a decrease in their demand for financing. Here we use the 2008 financial crisis that followed the collapse of the US bank Lehman Brothers.

This crisis can be considered as unrelated to the situation of French companies since it is related to the mortgage and housing market crisis in the United States. It nevertheless resulted in a very sharp rise in the cost of corporate debt in France (Chart 1) with an increase in bank and bond rates of more than 92 and 200 basis points, respectively, between January and September 2008.

2. We then need to isolate the effect on investment attributable to financial conditions alone from the effect linked to the impact of the shock on companies' growth prospects, i.e. isolate the supply and demand effects. To do this, we borrow from medicine and biology a method popularised in economics by the Nobel Prize winner in economics Esther Duflo: this method is based on so-called "treatment" groups, i.e. those subjected to the shock, and so-called "control" groups.

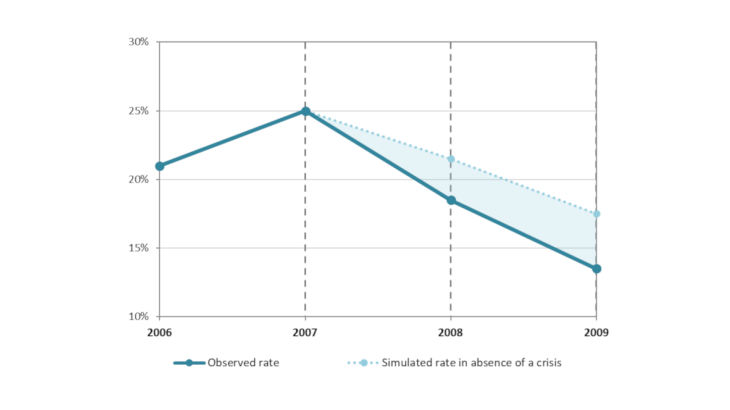

We thus compare two types of companies: (i) those with a large share of debt maturing just before the 2008 crisis and (ii) those with a small share of debt maturing at the time of the crisis. Our approach is based on the following observation: the debt maturity schedule does not influence investment behaviour; however, a shock to financing conditions at a given date will primarily affect companies that need to roll over their debt having reached maturity at the same time. Faced with a drop in supply or an increase in the price of financing, companies will potentially be forced to adjust their investment downwards. The control group thus shows what the investment dynamics would have been in the absence of the shock.

In practice: a stronger decline in investment among companies with large refinancing needs

First, we check that companies with large refinancing needs have seen an increase in the cost of their debt: indeed, their average cost of external financing has been about 1 percentage point higher than what it would have been in the absence of the shock. Then, we look at the investment response. According to our estimates, in 2009, the average investment rate of companies exposed to the refinancing shock is 4 percentage points lower than what it would have been in the absence of the shock, i.e. close to 20% of the average level of pre-crisis investment (Chart 2). By way of comparison, Almeida et al. (2009) estimate that investment by US firms facing large long-term financing needs in 2007 was almost 30% lower than its pre-crisis level.