- Home

- Governor's speeches

- What monetary policy narrative after For...

What monetary policy narrative after Forward Guidance?

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 12th of October 2022

Columbia University, New York, 11 October 2022

« What monetary policy narrative after Forward Guidance? »

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, governor of the Banque de France.

Ladies and gentlemen, dear students and professors,

I am very grateful to Dr. Patricia Mosser for the invitation to speak at Columbia University. I already had the honour of delivering a speech here in April 2017, and it is great to be back. The current context is obviously quite different from five years ago: today we face too high inflation – compared with too low inflation in 2017 –, and we are navigating through a geopolitical environment that looks unprecedented in its uncertainty. Due to this uncertainty, binding forward guidance from Central Banks appears less relevant, and has rightly been put aside in the recent past. But this is not an argument for returning to the secrecy that characterised central banking until the 1990s. One of the most topical questions for central banks is therefore how to ensure a “new predictability”.

Indeed, not having forward guidance does not mean, cannot mean, not having a narrative and a monetary strategy. Let me elaborate on this today, first laying out the reasons why we have to act in a determined way to deliver our 2% inflation target (I), then proposing some milestones on our normalisation path (II) and finally shedding light on one sensitive coordination issue (III).

I. We have to act in a determined way to deliver our 2% target

Inflation has reached levels that we have not seen in decades in the United States and in the euro area. HICP inflation in the euro area was 10.0% in September 2022 and excluding energy and food reached 4.8%. We decided to frontload our monetary policy normalization in September with a 75bp increase in all our policy rates, taking them into positive territory for the first time since July 2012. When anyone acts fast, there are always people to ask whether they are overreacting or could wait and move more slowly. For some in Europe, there would be two arguments in favour of inaction or at least caution: namely the supply-side origin of the shock and the risk of a recession. Let me tell why I don’t think such fears should derail us from our normalisation course.

On the nature of the inflation shock, there is obviously a significant energy and supply component in the current euro area inflation, reflecting pandemic-related supply disruptions in 2021, and on top of the sharp increase in energy prices this year after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. When central banks are faced with temporary supply shocks, they are often supposed to “look through” the immediate effect and extend the horizon over which inflation returns to target if necessary. But due to pressures along the pricing chain, inflation has not only heightened, it has broadened into industrial goods and services. In the euro area, core inflation has been above 2% since October 2021 and above 4% since July 2022.

Another feature of the inflation shock we are facing is its persistence. This may affect inflation expectations and lead to a de-anchoring. Current inflation levels require that we clearly show our monetary determination. We know, though, that the significant changes in monetary policy we have taken already will take at least a year or more to affect the economy. But it is our clear forecast and will to bring inflation back towards 2% within the next two to three years.

I am not convinced either by the trade-off between fighting excessive inflation and avoiding a recession. There are at least three clear reasons to prioritize price stability (i) legal: our mandate is focused on price stability (ii) political: our fellow citizens care first and foremost about inflation and its impact on purchasing power (iii) economic: entrenched inflation would mean less confidence, higher risk premia, and greater price distortion, and hence less long term growth.

Furthermore, the euro area economic starting point remains relatively favourable this year. The labour market is very strong with many vacancies and the unemployment rate stood at a historical low of 6.6% in July and August. Annual GDP growth in 2022 is expected to reach 3.0% according to the latest IMF projection – almost twice the US growth -, although a slowdown is forecast in the second half of the year after the robust growth of the first semester. We cannot exclude a temporary recession next year, especially in case of even more severe developments in the gas and electricity markets: but a short-lived – and limited – recession would be less detrimental than a protracted stagflation.

II. No Forward Guidance but some milestones on the monetary path

At its meeting in July, the ECB Governing Council formally ended its forward guidance on policy rates and switched to meeting-by-meeting decision-making. This move is appropriate, as we live through especially uncertain times and must not have our hands tied. That said, since we know that medium to long term interest rates are an important part of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy, having a yield curve that roughly corresponds to the policymakers’ own intentions is important: this is why we central bankers still want to provide some predictability about our reaction function. Of course, central bankers don’t actually follow a mechanical function; nevertheless, in normal times, simple feedback rules do a reasonable job in summarising what we expect to do. But we do not live in normal times and decision-making is more difficult than usual. What are the possible approaches to summarise our monetary policy framework, or narrative? I will first mention two opposite and extreme ones, before proposing useful milestones along the way.

1.Two polar approaches

The first, which I will call the “empiricist approach” would conduct policy looking only at currently observable data. Oversimplistic rules such as raising nominal interest rates until inflation returns to target would fall in this category. But this approach ignores the fact that monetary policy is subject to time lags - of up to two years to pass through fully to inflation - and that other factors can affect future inflation. It would put us at risk of overreacting. Making decisions on a meeting-by-meeting basis and the latest available data does not mean that we should be short-sighted, on the contrary forward-looking.

At a bit of a stretch of my definition, another example of the “empiricist approach” would be to simply follow the US Federal Reserve, perhaps with a gap to reflect different long-term neutral rates. This is obviously what countries with exchange rates pegged to the dollar do. Of course central banks are aware of what their peers are doing and there are undoubtedly some spill-overs from the actions of the Fed, not least through the effect on the exchange rate, on which I will have more to say later. But it would not make sense for the ECB to blindly follow the Fed: although inflation has dramatically accelerated in both economies, the underlying causes are not the same and hence the monetary policy stance should be different too. On the one hand, the energy supply shock is considerably more intense in the euro area which is a large energy net importer while the US is a net exporter. On the other hand, the post-pandemic recovery in aggregate demand has been much stronger in the US, with a much tighter labour market.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is what I would call the “academist approach” – although it comes from Lars Svensson, a one-time practitioner who was, among others, Deputy Governor of the Swedish Riksbank between 2007 and 2013. It would be to look purely forward and do inflation forecast targeting. The central bank then works out an interest rate path that is compatible with bringing inflation back to the target over the forecast horizon (and staying there). Simple models, such as the original Svensson’s one (1997), can be inverted to find a single policy interest rate – “the target-compatible rate”. With more complex models, target-compatible paths can be found through interest rate scenarios.

This approach is appealing in theory but raises several practical problems. First, it relies heavily on having a very accurate model and clear identification of the shocks hitting the economy, including how persistent these will be. The substantial forecast revisions over recent quarters underline quite how difficult it is to calibrate policy based on forecast targeting. A second, and more subtle, problem is the “stationarity” of most macroeconomic models. This is either true by assumption in standard New-Keynesian models or implicit in empirical forecasting models. For either reason, forecast inflation has a tendency to revert to the target or the historical mean under almost any scenario. Put another way, few applied macroeconomic models allow inflation to drift seriously away from the target for a persistent period of time. Many models implicitly assume a minimised probability of tail risks and shocks, and an exaggerated level of central bank credibility. As a consequence they will tend to underestimate the reaction of interest rates necessary to stabilise inflation forecasts at the target. Frankly, it is too early to tell where the terminal rate could be, even if this time could come in the future.

2. Several useful milestones along the way

The preceding section has highlighted that unequivocal rules set once-and-for-all are of low practical use in the current context; they put us at risk of either overreacting (empiricist) or underreacting (academist). Yet we should not give up having any reference points. In my view, the right balance consists of explaining an intermediary step along our path. Beyond this intermediary step, I believe it would be useful for the euro zone to set out a few decision criteria, both on interest rates and on the size of our balance sheet.

2.1 The neutral rate as an intermediary step

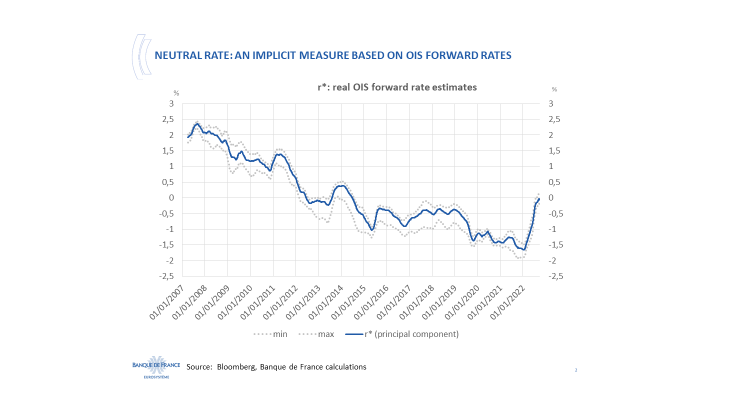

About the first part of the journey, the ECB will continue the process of normalisation until we reach at least the neutral interest rate. Of course, structural models of r* are notoriously imprecise and volatile but nevertheless help us understand the evolution of the natural rate over long periods of time.

In this slide I plot a measure with fewer technical assumptions: it uses the nominal OIS curve and ILS swaps to create forward one-year real rates at horizons of 4 to 9 years; this can tell us where markets expect real rates to settle once current shocks have dissipated. The solid line shows the first principal component as an estimate of r* using this approach, with a real neutral rate now just below zero. Based on a target inflation rate of 2%, the nominal neutral rate should then be a bit less than 2%. Given the fact inflation is far above target and still rising, we should reach this level before the end of the year. It is much more important to give the public this landmark than to spark speculation and public betting game on the size of the next move in October: this is why I won’t say anything today about this 50/75 bp discussion, which is premature especially in the current volatile market environment and the additional tightening of financial conditions.

2.2 A four-pronged approach for further interest rates decisions

What will happen from that point onwards? We probably won’t stop raising rates there, but we will enter another part of the journey: a more flexible, and possibly slower one, relying on a meeting-by-meeting precise economic assessment. This assessment should according to me follow a four-pronged approach, with four key indicators:

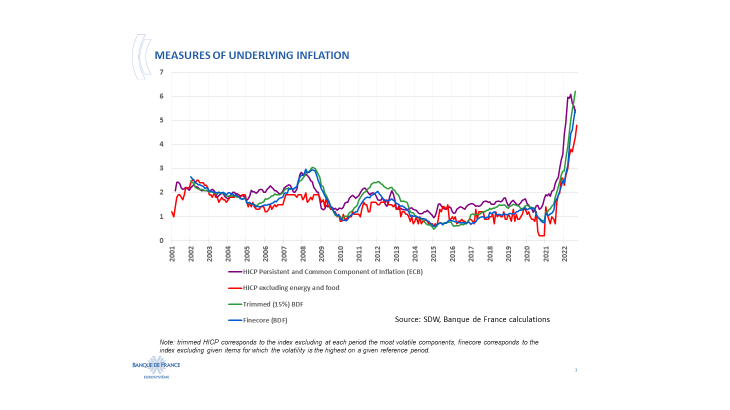

- First, actual inflation data, focusing on underlying inflation, as this is the part for which monetary policy is relevant. In particular we should look at measures of HICP excluding energy and food, and at negotiated wage growth: by the way, we don’t see so far signs of a generalised wage-price spiral. A turning point – which we don’t see yet – will be when underlying inflation is peaking.

Alternative measures of underlying inflation are less noisy than the standard index excluding food and energy and thus can better signal the medium term inflationary pressures. Indeed, in the aftermath of the pandemic, the three alternative measures shown on this slide (persistent and common component of inflation, trimmed and finecore ) have turned up earlier than the standard core index. And both in 2008 and in 2011-2012, they have also signalled earlier the easing of inflationary pressures.

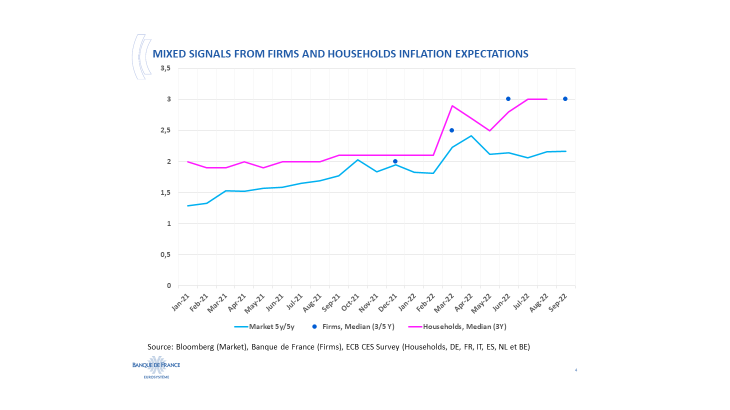

- Second, future inflation. We will obviously use our models and forecasts, but we should also give a strong attention to inflation expectations by financial markets and still more by economic agents: entrepreneurs and households are the real price- and wage-setters. Here so far, 3 to 5 year inflation expectations remain well anchored in markets, but with some mixed signals from businesses and households.

Any sign of stronger de-anchoring would call for a stronger monetary reaction.

- Third, we will have to look more closely at the economic activity and the cycle. In this tightening phase, unlike the phase of normalisation, the assessment of the state of the economy and projections for growth and employment will play a greater role. In case of a recession – even if it should be limited and temporary -, we would be certain to face calls to stop the tightening. This would miss the point: to bring inflation back to target, a recession is neither necessary nor sufficient per se. A more relevant discussion will be the assessment of the slope of the Phillips curves. The current and rapid increase in core inflation has led some observers to suggest that the flat Phillips curve paradigm of past decades is now obsolete. What is more likely is that price-setting in the economy is state dependent, with firms reacting by more and quicker to large shocks so that the Phillips curve is non-linear and convex. In any case, we cannot bet that a steeper Phillips curve will entirely do the job, allowing for a fairly “immaculate” disinflation.

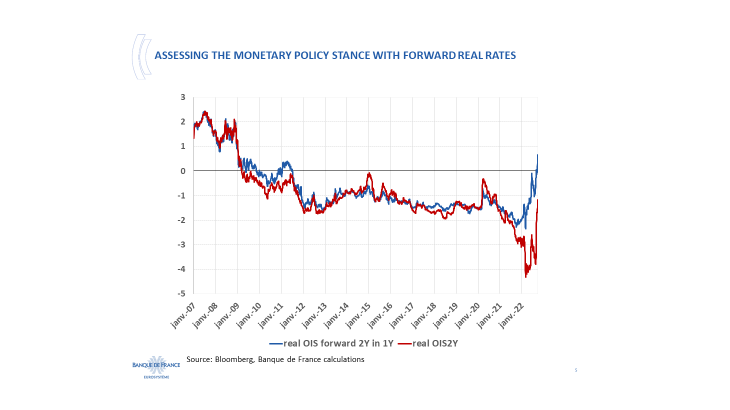

- Last but not least, we will need a benchmark to measure the degree of tightening. The real interest rate calculated with actual headline inflation would provide misleading signals. A better gauge is provided by medium-term forward real interest rates: they should be at least positive on all but the shortest maturities.

And they could become more positive as a result of two possible changes: downward move in inflation expectations, and further upward adjustments in expected nominal interest rates.

2.3 Some initial thoughts on the balance sheet

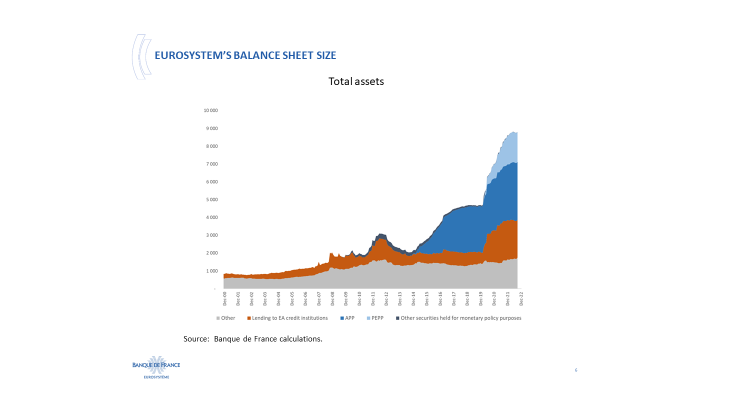

Another issue that we will need to confront is the normalization of our balance sheet. It has expanded in recent years through numerous programmes (APP, PEPP, TLTROs,..) and is now just short of 9 trillion euros.

It would not be consistent to keep a very large balance-sheet for too long in order to compress the term premium, whilst at the same time contemplating tightening policy rates above neutral. In addition, rising remuneration on very large excess reserves may alter the transmission of the desired tightening through the bank channel. But obviously, this question is less pressing than the rise of interest rates to neutral, and should come only at a later stage.

Let me simply put forward at this stage a few preliminary principles that could in my personal view guide the normalisation of our balance sheet, in due time:

- First, our key interest rate should remain our primary instrument to adjust our monetary policy stance. The size of our balance sheet should be used as a complementary policy tool, whose effects are more difficult to calibrate or fine-tune.

- Second, we should follow a clear sequencing regarding the various programmes: (i) the reimbursement of TLTROs comes first, and we should avoid any unintended incentives to delay repayments by banks (ii) at the other end, PEPP should be reinvested until the end of 2024, as stated (iii) this leaves inbetween APP for which the Governing Council has said that reinvestment will continue in full until “well past the date when it started raising the key ECB interest rates”. Here we could start earlier than 2024, maintaining partial reinvestments but at a gradually reduced pace.

- Third, the phasing out of the asset portfolio should be orderly, announced cautiously and well in advance. The ‘stock effect’ of asset holdings, which is the key transmission channel, primarily depends upon the expected end-point of the balance sheet normalisation, in terms of both the terminal date and size. Fluctuations in the pace of the run-off during the travel to destination do matter less.

- Fourth, as taught by US experience in 2017-2019, the pace of the balance sheet reduction should not be left completely on “automatic pilot”. Starting slowly, assessing markets reaction, and gradually accelerating seems like a sound approach. Some flexibility should be kept, in case of sudden liquidity shocks. Indeed, the ‘flow effect’ may temporarily play a role when market liquidity abruptly dries up.

III. A sensitive co-ordination issue

This is the way we should run our domestic monetary policy. But in conclusion, let me touch a sensitive coordination issue between various monetary policies. Given the financial importance of the dollar, and the need for the Fed to tighten decisively in order to reach its own price stability objective, other Central banks could be exposed to a dilemma. This is not exactly the one put forward by Helene Rey in her famous 2013 paper, but a delicate trade- off as a consequence of free capital movements:

- Some Central banks already fighting inflationary pressures could be at risk of overtightening to avoid an excessive slippage of their currency. This would be mainly but not exclusively the case for emerging markets, and justifies the fear expressed by M.Obstfeld and others of an excessive global monetary tightening. The IMF judges nevertheless that we are not there yet, and I agree.

-Others would see a significant fall of their currency (versus the dollar) if they seek to maintain accommodative domestic monetary conditions. This could explain the recent intervention by Japanese authorities in favour of the yen.

As said earlier, I think that the ECB should and can run its own monetary course. Not only today, but as a structural consequence of the significant weight of the euro area in the world economy: I stressed it four years ago in our IMF Bali meetings. Obviously the exchange rate matters for our inflation outlook: we don’t target it, but we look at it closely.

That said, I wouldn’t conclude that we are not at risk of coordination failures. Let me share two reflections in this regard:

1. Our collective “doctrine” on monetary policy, in the G7 and G20, remains valid: that we central banks target domestic price stability and not exchange rates. But it implies as a counterpart an in-depth and confident dialogue, in Washington, Basel and elsewhere, on our intentions: there should be mutual predictability of policy making. We will achieve the closest to a cooperative solution if we avoid significant surprises between policy makers. As Jay Powell rightly said in 2019 in Paris “Pursuing our domestic mandates in this new world requires that we understand the anticipated effects of these interconnections and incorporate them into our policy decision making.”Lael Brainard reiterated this welcome statement no later than yesterday: “The combined effect of concurrent global tightening is larger than the sum of its parts. The Federal Reserve takes into account the spillovers of higher interest rates, a stronger dollar, and weaker demand from foreign economies into the United States, as well as in the reverse direction”.

2. But there can be market misperceptions of policy intentions or overshooting, and exchange rates can become fundamentally misaligned. Under such circumstances, there were G7 interventions in the past. Several of them were effective, which we shouldn’t forget. But in order to be such, let me only remind they had to fulfil two conditions: (I) to result from a shared diagnosis about fair levels of exchange rates and possible misalignments - here the IMF traditionally played a strong role as a trustworthy and third party expert - and (II) to be coordinated in their implementation, or at least in their communication.

Conclusion

Let me wrap up: we are totally committed to our end objective – inflation back to 2%; we are more open about our path to meet this objective. But we should have an orderly use of our palette of instruments: first, interest rate hikes, with a rapid increase towards neutral and then a possibly more flexible pace; second, and at some later stage, balance sheet normalisation, with a more cautious start followed by a gradual amplification. Giving such partial predictability to markets is not being precommitted as with a precise and binding forward guidance; but it will help to align financial conditions with our target, and to avoid excessive volatility. And rest assured we will maintain two strong virtues for uncertain times: pragmatism – and data dependency – rather than pre-set ideology; international coordination – and in-depth dialogue – rather than fragmentation. Thank you for your attention.

Updated on the 27th of November 2023