- Home

- Governor's speeches

- Short-term and long-term yields: a diver...

Short-term and long-term yields: a diverging perspective?

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 31st of January 2025

OMFIF, London – 31 January 2025

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure to be in London today for this OMFIF meeting and I am grateful for your kind invitation. By the way, today is history for our single currency, the euro: we announced this morning a decisive step toward future banknotes. We will have to decide between two possible themes by next year: culture, with six prominent Europeans, and rivers and birds. These banknotes will much better represent Europe, and embody the historically high support of 81% of European citizens for their single currency. That said, I would like to share with you some insights about two recent monetary developments. I will first comment on short-term rates and yesterday’s monetary policy decision (I) and then highlight some challenges against a backdrop of rising long-term rates (II).

I. On ECB short-term rates: a clear direction, and a pragmatic pace

Yesterday, our Governing Council, led by President Lagarde, decided unanimously a fifth cut, and a fourth in a row. Compared to other major central banks, ECB has been the earliest to cut, the lowest to go, and probably has the clearest path in its monetary course. To put it in a nutshell: as the ECB president said, we are precisely on track in our victorious fight against inflation. We know there is a discussion whether this success is the result of luck – reversal of commodity prices – or of central banks work. Both, to be honest: but monetary policy played its significant part. There are different models used by various European NCBs and the ECB itself: but all of them converge to a conservative estimate of monetary policy having reduced inflation by about 2% in 2023 as well as in 2024.

Looking ahead, we should be sustainably around our 2% inflation target by this summer. The French flash inflation in January published this morning, stable at 1.8% and slightly lower than expected, is good news on this road: services inflation in particular seems to be receding. We see significant wage deceleration and are hence confident on core inflation decrease, including services. And on activity, we avoided recession last year with 0.7% growth, and will again avoid it this year. But the somewhat disappointing GDP stagnation in Q4 published yesterday confirms that risks on growth are clearly tilted to the downside.

With such a “disinflationary slowdown”, the direction of the travel is clear: our monetary policy will go from restrictive towards neutral, and should support a gradual recovery while ensuring inflation is at our target. How fast and how far should we go in this travel? This is where what I call “agile pragmatism” and our data driven approach will guide us. I don’t want to bother you today with a sophisticated discussion about the precise level of R*… Furthermore, long term yields have increased, limiting the easing of overall financial conditions.

II. A more challenging view on long-term yields

A) Unusual divergence between short and long-term rates

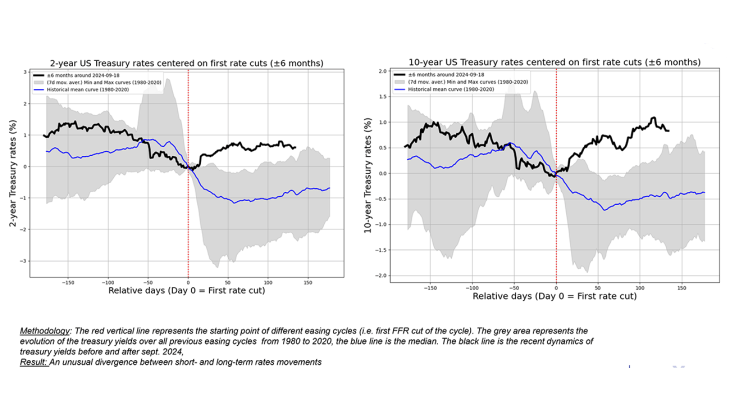

The ECB, since last June, and the US Federal Reserve, since last September, began a rate cutting cycle and both have reduced their policy rates by 100 bp last year. But over the same period longer term yields have increased, particularly in the US which is very unusual compared to previous easing cycles. The US 10-year yield is now up by more than 80 basis points since the Fed started cutting rates and the so-called “Trump trade” began while previous easing phases were initially associated with a fall in long yields.

US Monetary Easing But Medium- To Long-Term Rates Increase

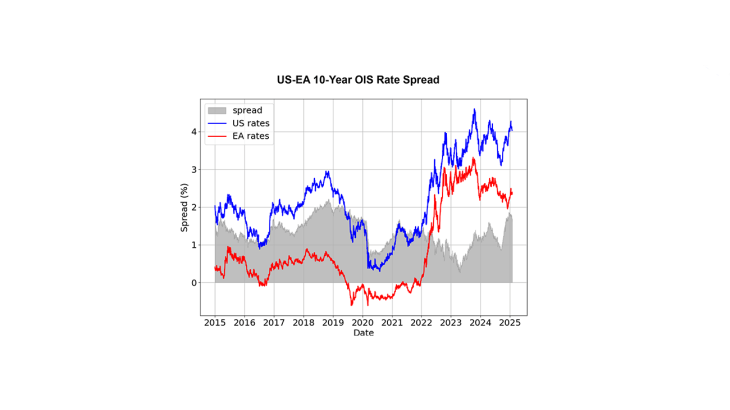

In the euro area, long-term rates have also increased but to a lesser extent and the US 10-year spread relative to EA OIS has risen by 80 bps over the same period.

The US 10-year Spread Relative To EA OIS Has Increased

B) What can explain this rise in long yields?

The sovereign debt trajectories and the elevated global policy uncertainties are likely the two main factors. Fiscal deficits remain high in many advanced economies (US, UK, FR); even in Germany, fiscal policy might become more expansionary after the elections. Uncertainty about the trajectory of public finances is putting upward pressure on sovereign yields.

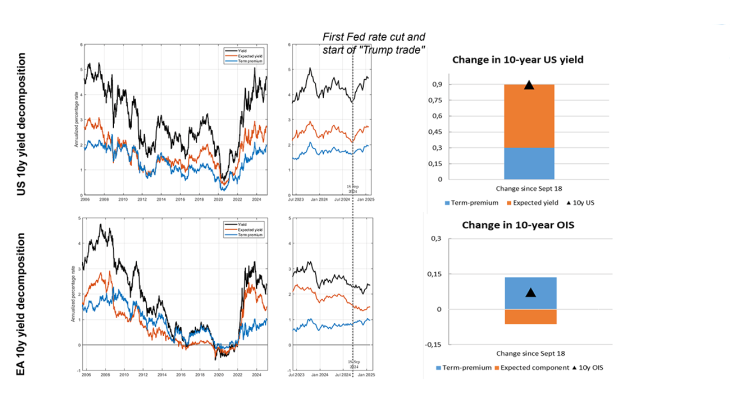

Macroeconomic factors are also at play, even though quite differently on both sides of the Atlantic. In the US, the risk of future trade restrictions and possibly immigration policies keep uncertainty about the outlook and inflation high, directly affecting risk premia. In the short run, these measures are akin to negative supply shocks and likely to be inflationary, before possible reversal in the longer run as aggregate demand could weaken. For now, the growth perspectives remain strong in the US, as confirmed by recent robust labour market data, and option-implied distributions of inflation expectations show upside risks to inflation. In that context, markets expect the Fed to cut interest rates less this year than previously anticipated. The expectations component is estimated to account for about two-thirds of the increase in the 10-year Treasury yield since mid-September.

Rise In 10-year Rates: Both Term Premium And Expectations

The macroeconomic picture is different in the euro area. The disinflation trajectory is more clear-cut and the macro outlook is weaker. The contagion to European yields from higher US interest rates has thus been limited so far: monetary policy perspectives could and should rightly decouple. But spillovers on the bond markets operate also through the global risk channel. In a more uncertain global environment, investors require higher compensation for lending long term, which results in higher term premia. The contribution of the term premium to the change in OIS 10-year rates since mid-September is almost 15 bp. The impact of this rise in the term premium on financial conditions in the euro area is however mitigated by the depreciation of the euro/dollar exchange rate which has occurred during the same period.

C) The role of unwinding QE shouldn’t be overstated

Some commentators argue that the end of QE has contributed to the rise in long-term yields. This interpretation goes back to the initial objective of QE. Asset purchase programmes were launched in times of crisis and when rates were at the effective lower bound (ELB) for two reasons: 1) to preserve an effective monetary policy transmission when specific market segments were under strain – which is not relevant today, and 2) to provide additional policy space when required (i.e. monetary stance purpose). In that latter case, purchases of long-term bonds aimed at compressing the term premium and therefore the long term yields, to stimulate aggregate demand.

In principle, “quantitative tightening”, i.e. the full unwinding of all large scale asset purchases would drive the market back to the status quo ante. But there are two reasons to discount this; and the wording itself of “QT” is somewhat misleading. First, passive and bounded “QT” is not the symmetric of active and open-ended QE: QE ramped up quickly but unwinds much more slowly. Recent research finds that asset purchases had powerful effects during periods of market stress. We should not expect to go back to crisis yields. As a matter of fact the term premium has been contained since the end of the reinvestments under the APP (July 2023) and the PEPP (December 2024). Second, QT is completely predictable and none of the parameters have changed since last summer. For both programmes the Governing Council announced months in advance the date at which reinvestments would be discontinued and market reactions at that time were very muted.

D) To conclude, let me draw a few lessons regarding the use of balance-sheet tools in the future.

- First, when the primary goal of QE is transmission or financial stability, there is no reason to hold the assets to maturity or to take excessive duration risk. There is no obligation to re-sell at short notice but there should be an option open at any time. More generally, QE is not necessarily the first-line instrument to restore appropriate transmission. TLTROs or large scale liquidity provision are other effective tools to address transmission impairments in the banking system.

- Second, when the goal is to ease further the monetary stance while interest rates have reached their lower bound, then we should distinguish whether we aim to provide liquidity (i.e. volumes) or to reduce long-term rates (i.e. prices). If the primary objective is to inject liquidity, it should not be done through purchases of long-term bonds, but by lending short term or at floating rates for LTROs. By the way, these were a powerful and successful innovation of the ECB, not used in the US. But the initial pricing of TLTRO III at quasi-fixed rates was not fully appropriate and had to be later recalibrated. “Core QE” – i.e. purchasing and holding long-term bonds – should be used for the purpose of reducing the term premium and therefore the long-term yields. If this purpose is clear and warranted, we should admit that it entails taking interest rate risk onto our balance sheet, and hence possible losses as we have seen recently. We should then be ready to accept such risks, while looking more closely at the average maturity of the purchased portfolio.

- In our portfolio holdings, we should prioritize government and supranational bonds to limit our direct balance sheet exposure to the non-financial corporate sector. That being said, such programmes are not and should never be designed to fund governments nor to help fiscal stimulus.

- Fourth and finally, we should not condition one instrument on another. Doing so creates communication issues if one programme has to be stopped. For instance, using asset purchases to make forward guidance more credible can turn out to be unwise, as we saw early 2022 when we had to gradually discontinue asset purchases before being able to raise rates.

I will end with a few lines from a French poet, Joachim du Bellayii in the 16th century: “Happy is the one, who like Ulysses, has completed a beautiful journey (…) And has then returned, full of wisdom and reason”. The last ten years have been anything but a beautiful journey for us central bankers; however, victory over inflation is now in sight. Like Ulysses, we have been through an unprecedented sequence of monetary policy challenges: this valuable experience gave us humility but also some confidence to face the next steps ahead. These include adjusting while keeping our toolkit, which will be a focus of our interim Strategy Review. Thank you for your attention.

iDu (W.), Forbes (K.) and Luzzetti (M.), “Quantitative Tightening Around the Globe: What Have We Learned?”, NBER Working Paper n°32321, April 2024 ; Acharya (V.), Chauhan (R.), Rajan (R.) and Steffen (S.), “Liquidity Dependence and the Waxing and Waning of Central Bank Balance Sheets”, December 2024

iiDu Bellay (J.), The Regrets, 1558

Download the full publication

Updated on the 31st of January 2025