- Home

- Governor's speeches

- International monetary spillovers: finan...

International monetary spillovers: financial and intellectual linkages

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 11th of January 2024

Bellagio event in Paris – 11 January 2024

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

It is a great pleasure to welcome the Bellagio group in Paris. The 80th anniversary of the D-day Landings this year is an important reminder that American and European histories are so closely inter-twined. Today this relation materialises through tight economic and financial linkages, the subject of my talk this afternoon.

1. Financial interlinkages and global monetary policy spillovers

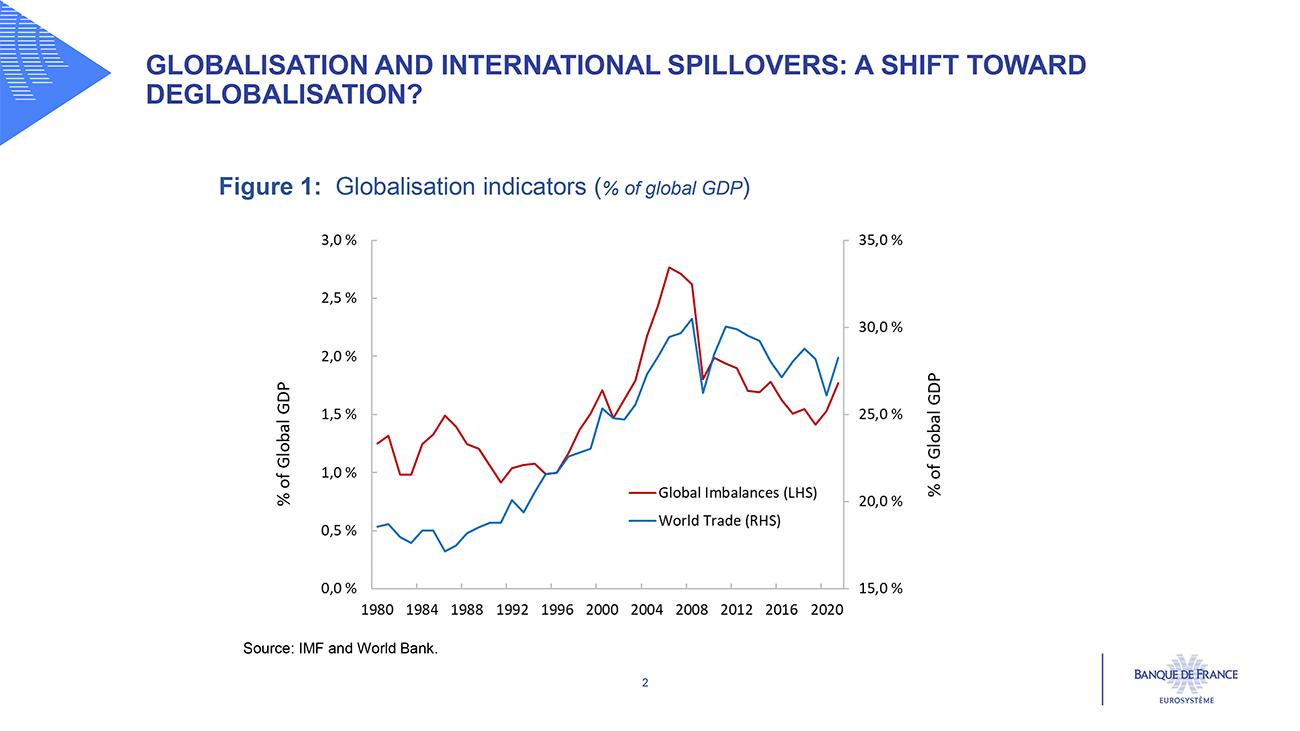

In a globalized world, economies are linked through trade and financial flows. While these linkages help when domestic demand falters or domestic savings are scarce, they can also transmit adverse developments across borders. This is the essence of international risk sharing, which if taken to the limit would imply a common global cycle. Due to global value chains, spillovers and co-movements in goods production have indeed risen over recent decades. However, there is less commonality in the production of services. The rising share of services in overall production has offset the increased integration of goods, so that the co-movement of economic activity between countries has not increased. The disruptions caused by Covid and Russia’s unjustified invasion of Ukraine have shown the fragility of extended supply chains. Noticeably, there had already been some retrenchment in globalization indicators following the Great Financial Crisis, as shown in Figure 1.

However, fewer spillovers do not necessarily imply less volatility. In autarky, countries depend entirely on their own industries and there is less ability to adjust to domestic shocks.

On the financial side, the globalized economy features similar patterns. On the one hand, increased openness implies rising exposure to the global financial cycle . On the other hand, improved policy credibility and better monetary policy frameworks have allowed more countries to have freely floating exchange rates and independent monetary policy to meet domestic objectives.

However, monetary policy still generates important financial and trade spillovers. As a group of countries tightens monetary policy, their currencies can appreciate and potentially generate inflation spillovers to the countries on the other side of that appreciation . In the case of a global inflationary shock, it is important to avoid ‘reverse currency wars’ as countries seek to escape inflationary depreciation. But coordination does not mean that the pace of monetary tightening must be equal across all economies, as each has its own specificities. For example, relative to the US, fiscal policy has been less expansionary across Eurozone economies, and the euro area also features a stronger predominance of bank credit relative to market credit, which can be important for the transmission of monetary policy.

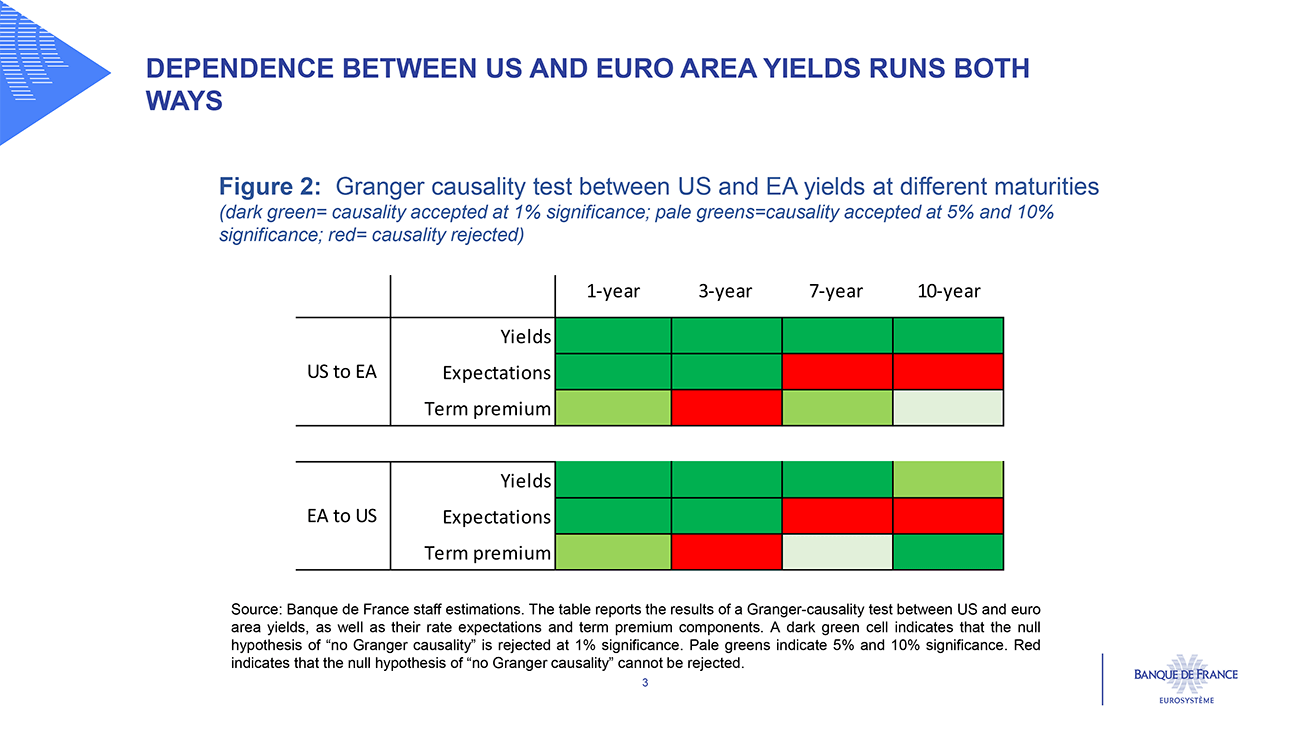

But monetary policy works also through market expectations of future policy rates, which can change quickly and are formed within a global market, creating an additional channel for spillovers. When one central bank makes a move, markets’ attention turns to its peers in search for cues on their likely next decisions. Indeed, there are strong mutual interdependencies between US and euro area yields over time: going beyond simple correlations, estimates based on Granger-causality tests suggest that causality runs both ways (Figure 2).

Interestingly, this two-way causality holds for rate expectations at short to medium term maturities – the typical monetary policy horizon, as shown by Figure 2; and at longer maturities, causality mainly runs via the term premium. The latter is consistent with the dominance of global macro-financial factors as drivers of the term premium component of long-term rates.

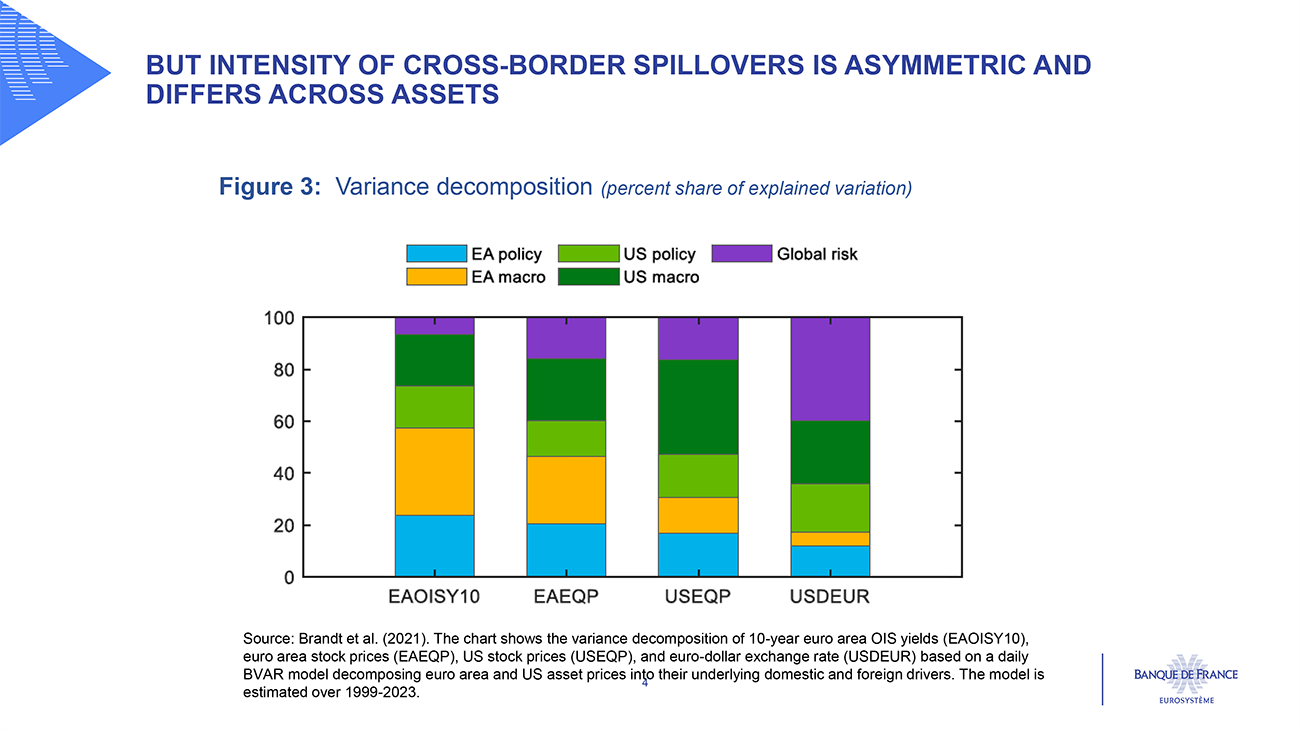

While spillovers between the US and the euro area are mutual, their intensity is asymmetric. US factors explain a larger share of variations in euro area yields than the opposite, as shown by Figure 3.

And this share varies across assets: US spillovers exert a larger impact on stock prices than on bond yields, for example. At the same time, there seems to be rising sensitivity of euro area rates to US news of late, amid sustained yield volatility on both sides of the Atlantic. With inflation largely driven by common global factors such as energy prices over recent years, it seems that markets use US data as a leading indicator for inflation releases in other countries, implying that rate expectations adjust in tandem.

2. Intellectual spillovers

Global interdependence is not only about economic or financial linkages, but also about ideas flowing across borders, “intellectual spillovers”.

As the issuer of the main international reserve currency and home of the largest and most liquid financial market, the US has a prominent position in shaping global financial markets. This is particularly true for US monetary policy, which is an important driving force of the global financial cycle. Several unconventional monetary policy measures first put in place in the US were later adopted by other countries, such as large-scale asset purchases or interest rate forward guidance. Reflecting the US central role, most of the economic literature first uses US empirical applications before applying it to other countries. There are however counter-examples to this. A conference hosted by the Banque de France in October showed that there is active research using euro area data and there are clearly lessons to draw from the euro area for other central banks.

In fact the direction of spillovers is not just one way. The inflation-targeting framework was pioneered by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the Riksbank, among others. And the ECB, from its inception, opted for a 2% numerical inflation reference in the definition of price stability that is now the standard worldwide. Fixed-Rate Full Allotment (FRFA), Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs), Negative Rates, or measures aimed at restoring monetary policy transmission such as the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), were all novelties that the ECB brought into mainstream central banking.

This reciprocity is also visible in the growing interactions between the ECB and the Federal Reserve at all levels. This greatly helps overcome the Atlantic barrier. Let me for example mention the Research area, where frequent exchanges are taking place among staff, and the now established practice of bilateral video conferences on topics of relevance to both institutions. While I welcome these growing interactions, let me also stress that more needs to be done to facilitate publication of euro area research in US-based reviews and its broader dissemination through appropriate citations.

3. International cooperation

Central banks have made bold progress in collectively managing spillovers, particularly during crises. One good case in point is the development of a network of standing currency swap arrangements across central banks to provide emergency liquidity, which contributes to foster global financial stability. Likewise, the strengthening of the Basel Framework helps reduce adverse spillovers, and the banking turmoil of early 2023 underlines the importance of fully implementing the Basel III rules. Furthermore, in order to ensure financial stability, central banks strive to act efficiently in many areas. We are doing more than simply safeguarding the past and fixing problems. Marked progress has been made to secure payment systems and infrastructures, supervise financial institutions while closely monitoring vulnerabilities and assessing new risks such as those stemming from Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs), crypto-assets and the emergence of Decentralized Finance (DeFi). Let me add that, within their mandate, cooperation between central banks should be strengthened to promote climate mitigation policies across their fields of intervention.

The BIS, an international financial institution owned by central banks, is a good example of a well-functioning and efficient multilateral organisation. Trust, cooperation and respect among members are three building principles of the BIS that are key ingredients for effective international cooperation.

Finally, central banks are very active in promoting research and steering global networks such as the International Banking Research Network and the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System, for which Banque de France has a leading role. Looking forward, central banks likely need to consider the effects of artificial intelligence, which will require a strengthening of international cooperation.

To conclude, spillovers can take very different forms and can change substantially over time. The Bellagio Group is ideally positioned to discuss these issues due to its unique composition, with central bankers, Treasury officials and academics around the table. For this reason in particular I very much value our discussions at the Bellagio Group.

1 Bonadio, B., Huo, Z., Levchenko, A. A., & Pandalai-Nayar, N. (2023). Globalization, Structural Change and International Comovement, NBER Working Paper #31358

2 Rey, H., (2013), Dilemma not trilemma: the global cycle and monetary policy independence, Proceedings - Economic Policy Symposium - Jackson Hole.

3 Schmidt, J., Caccavaio, M., Carpinelli, L., Marinelli, G. (2018). International spillovers of monetary policy: Evidence from France and Italy," Journal of International Money and Finance.

4 London, M., Silvestrini, M. (2023) US Monetary Policy Spillovers to Emerging Markets: the Trade Credit Channel.

5 Berthou, A., Schmidt, J. (2022) Exchange rate pass‑through to import prices in France: the role of invoicing currencies, Bulletin Banque de France 242/6.

6 Alder, M., Coimbra, N., Szczerbowicz, U. (2023) Corporate Debt Structure and Heterogeneous Monetary Policy Transmission, Banque de France Working Paper 933.

7 Ca’ Zorzi, M., Dedola L., Georgiadis G., Jarociński M., Stracca L. and G. Strasser (2020), “Making waves – Fed spillovers are stronger and more encompassing than the ECB’s”, ECB Research Bulletin No 83.

8 Miranda-Agrippino, S. and H. Rey (2020), “US Monetary Policy and the Global Financial Cycle," The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 87, November 2020, pp. 2754-2776.

9 Examples of recent IBRN research papers: Andreeva, D., Coman, A., Everett, M., Froemel, M., Ho, K., Lloyd, S., Meunier, B., Pedrono, J., Reinhardt, D., Wong, A., Wong, E., and D. Żochowski (2023), “Negative rates, monetary policy transmission and cross-border lending via international financial centres , ECB working paper no 2775, february”. Correa, R., Goldberg, L. S., di Giovanni, L. and C. Minoiu (2023), “Trade Uncertainty and U.S. Bank Lending,” NBER working paper 31680, November. Windsor, C., T. Jokipii and M. Bussiere, 2023 “The Impact of Interest Rates on Bank Profitability: A Retrospective Assessment Using New Cross-country Bank-level Data”, RBA Research Discussion Papers rdp2023-05, Reserve Bank of Australia.

Download the PDF version of the slides

Updated on the 25th of July 2024