- Home

- Governor's speeches

- Governance of public expenditure and pub...

Governance of public expenditure and public services: is there any hope left?

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on 19th of June 2023

Conference at the Académie des sciences morales et politiques

Paris, 19 June 2023

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France.

Dear Chairman,

Dear Permanent Secretary,

Dear Academicians,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is an honour for me to speak before you today and I wish to warmly thank your Chairman and my esteemed predecessor, Jean-Claude Trichet. This year, your collective discussion focuses on the theme of "Good governance". Six years ago, at the invitation of Michel Pébereau, I had the opportunity to use the theme of "Reform" to reflect upon international financial regulations. Today, I will tackle a different aspect: good governance in the public sphere. I would like to thank a number of people who are committed to this cause and who have been kind enough to be here today. As the head of a public institution and a fervent supporter of the public service – and also as a citizen – I consider this to be an essential matter. France appears to be drifting towards a "strange defeat", or, at the very least, a gloomy resignation, reflected in constantly increasing government expenditure and public debt (I), together with diminishing intellectual investment in economic optimisation and public management strategies. (II) There is also a growing feeling that essential public services are continuing to deteriorate. In the face of this public crisis, is there any hope left? I will close my presentation with a practitioner's conviction: yes, transformation and management of public services are indeed possible! (III)

I. Our public finances have steadily deteriorated over time

The "strange defeat": getting left behind in Europe

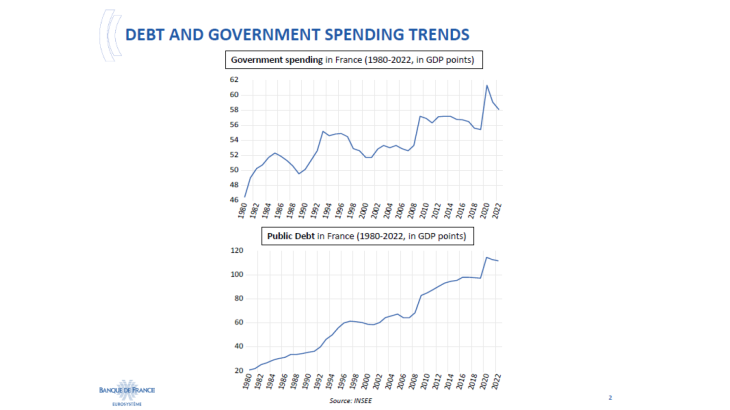

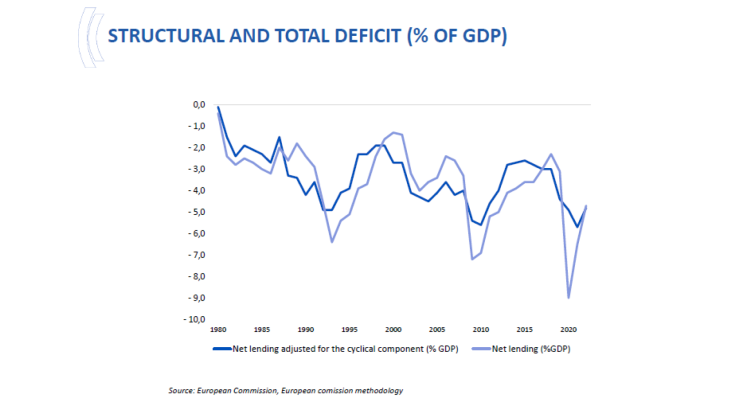

Our public finances have been steadily deteriorating for over forty years. In 1980, our public debt amounted to only 20% of GDP. It currently represents almost 112%, a figure that has barely come down since the Covid shock, and by less than our European neighbours. This steady increase can be explained by the government expenditure ratio, which has risen from 46% in 1980 to 58% at present, systematically generating annual deficits.

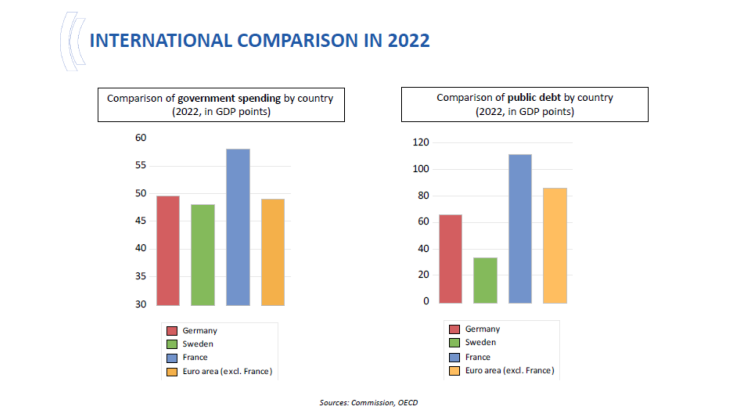

For these two key ratios, France is currently well above the average for the euro area excluding France (i.e. government expenditure ratio of 49%, public debt ratio of 86% in 2022).

France joined the euro area with a public debt ratio equal to that of Germany (59% in 2001); since then, Germany's debt has increased by 8 points, while France's has risen by 53 points.

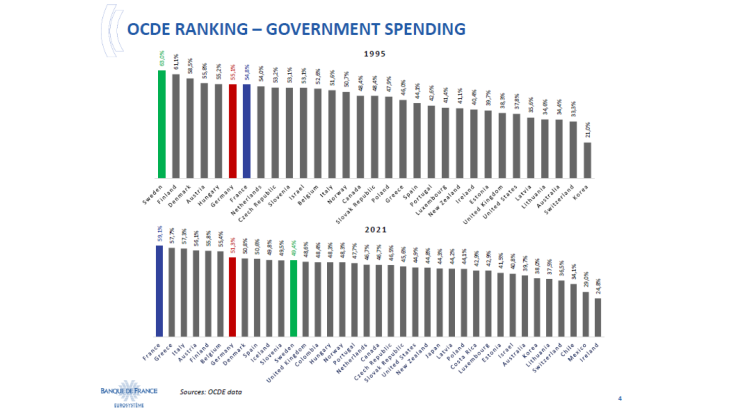

This sets France apart from most of its European neighbours, who all share the same social model, in which I am a firm believer. Let us take two comparisons: Germany and Sweden. Between 1995 (beginning of the OECD statistical series) and 2021, Germany reduced its government expenditure ratio from 55% to 51%, and Sweden from 63% to 49%. France has risen from 7th to 1st place, replacing Sweden as the government expenditure record holder.

Shedding light on government spending differentials

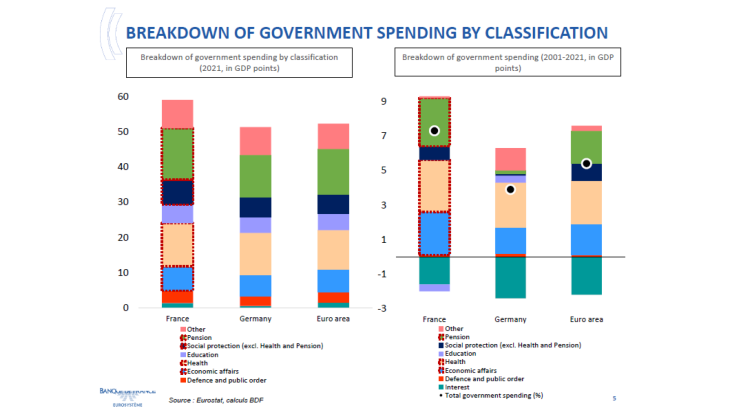

But there is a positive lesson here: the German and Swedish examples, along with many others, demonstrate that recovery is possible... in other countries. After the crisis of the early 1990s, Sweden for example, introduced a new governance framework and conducted a strategic review of its spending. This brings me to the composition of our expenditure when compared with Germany and the euro area as a whole.

What sets France apart in particular is the level of its social protection expenditure, which amounts to 34% of GDP, compared with a euro area average of 29.5%. This additional cost applies to spending on pensions, healthcare and unemployment benefit. Another example is housing benefit, which amounts to 0.9 points of GDP in France, compared with an average of 0.2 points in the euro area excluding France. Consequently, France's spending has risen much more sharply since the early 2000s than that of its euro area counterparts. If we wish to get public debt back down to below 100% of GDP - its pre-Covid level – there is only one solution, and that is stablising public spending in volume terms, after having increased it by more than 1% a year on average for 20 years.

This chronic deficit has been shared by all governments and parties in power for over forty years, despite some temporary improvements in the late 1990s and early 2010s.

Aside from the much greater 'ratchet effect' of spending in France than in other countries, this French malaise is reflected in – and partly explained by – two symptoms of a more political nature.

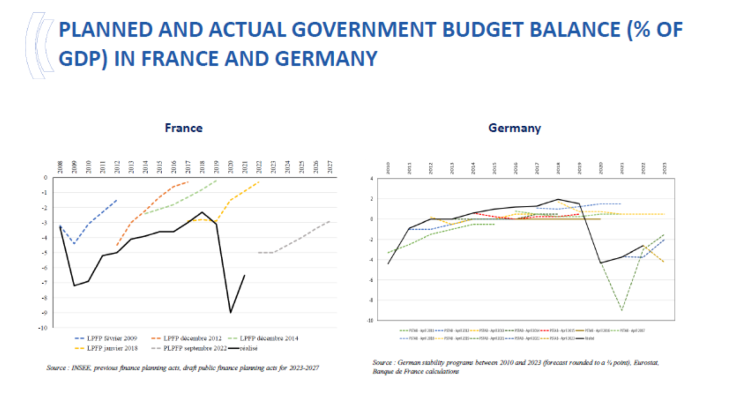

Two symptoms of the French malaise

First, we are multiplying the number of commitments to budgetary targets, but so far we never adhere to them. Management of public finances is deemed to have evolved into a more multi-year process - which is a good thing - with the adoption of public finance planning acts from 2009 onwards, but also as a result of the requirements of the EU Stability and Growth Pact since 1999. However, when it comes to executing the process, the comparison with Germany is cruel indeed: our German neighbours systematically outperform their forecasts and commitments, while we systematically do worse than ours.

These persistent and significant shortcomings severely damage our credibility in Europe and in the eyes of all French citizens. I would like to applaud the determination currently being shown at the "Assises des finances publiques" (round table conference on the public finances) in Bercy. Some people are calling for more ambitious targets, but a first real revolution would be to stick to existing ones. This requires being specific in terms of how savings can be made, and then firm and tenacious in the implementation phase.

Second, we tend to focus public debate and promises on taxes, thereby confusing the symptom with the cause. This may be described as a sort of "Bermuda triangle" of fiscal frustration: (a) successive tax cuts since 2014 have fuelled our deficits and are now costing us around 2 points of GDP (b) however, French people actually express major political doubts about these tax cuts: they are never considered sufficient (c) the constant change in tax measures is economically ineffective as these changes make households and SMEs unfamiliar with them; tax instability and complexity interfere with the expectations of economic players.

II. At the same time, intellectual and academic investment have continued to decline

Public initiatives that rarely go anywhere

Over these same decades, public reform has been the focus of successive but diminishing expectations. In 1989, the government of Michel Rocard launched the "Renewal of Public Service” programme. The adoption of the Organic Budget Law (LOLF) in 2001 represented a great source of hope with its focus on performance and tracking results by public mission - without, alas, ever having been properly “adopted” in either public or parliamentary debate. Since the remarkable work of the Pébereau Commission in 2005 on public debt, there has been a succession of plans for reform, from a General Revision of Public Policy (RGPP) under President Sarkozy, through Modernisation of Public Policy (MAP) under President Hollande, to Public Action 2022 under the current presidency. More recently, another revision of the Organic Budget Law adopted in 2021 aimed in particular to improve multi-year oversight of the public finances, by introducing a nominal public spending target in billions of euros [rather than in GDP points], as well as a three-year ministerial performance trajectory. Unfortunately, the first public finance planning act under this new framework is struggling to be adopted.

The absence of an overall perspective, overlapping sectoral reforms and successive waves of decentralisation have resulted in a lack of consistency and "a loss of vision by the administration".[i] I am perfectly well aware of how difficult it is for politicians and our elected representatives to deal with the unrelenting pressure of urgency, exacerbated by a succession of unprecedented crises. However, the growing tyranny of "the news cycle" and of emotions tends to mask the structural challenges we face. De Tocqueville's thoughts on the Ancien Régime and the Revolution are strikingly apposite today: "[The government] seldom undertakes or soon abandons the most necessary reforms, which in order to succeed, demand a persevering energy".[ii]

The increased use of assessment has also been a disappointment in terms of improving public sector efficiency. Ex ante assessments, based on the introduction of compulsory impact studies in 2009, have remained under used as a management tool, "too often appearing as a self-serving justification for the laws they accompany".[iii] Ex-post assessments have also been developed in France either by public bodies or academic research, but contribute more to methodological debates than to any real objectification conducive to action.

Dwindling academic research

Meanwhile, what can we say about academic and economic research in this area? In the 1980s and 1990s, this was mainly influenced by the New Public Management (NPM) school of thought, which adopted management methods from the private sector, with a focus on incentives for public servants and more variable pay. The Virginia School’s Public Choice theory (Downs, Buchanan, Tullock) even proposed to turn the concept of public action on its head: individualistic officials and policies could pursue private interests rather than spontaneously acting in the general interest. I personally remember the shock that I and the whole generation of civil servants around me experienced when Jean-Jacques Laffont questioned the principle of the "benevolent state" in a presentation he made to the Economic Advisory Council (CAE) in 1999. Fortunately, Jean Tirole has since clarified and qualified the analysis in "Économie du bien commun,[iv] where he called for the creation of "real public service bosses", and for them to be afforded "considerable managerial freedom accompanied by strict ex-post evaluation". NPM gave rise to performance incentives based on indicators and assessments. The outcome of these measures would appear to be useful without being decisive, and the illusion of NPM has gradually dissipated. In particular, measuring the performance and quality of certain public services sometimes runs into intrinsic measurement difficulties.[v]

More than twenty years on from this research, twelve years after Philippe Aghion and Alexandra Roulet called for a "Rethinking of central government”,[vi] it is regrettable that macroeconomic analysis is still of so little assistance to public management. Research literature focuses almost exclusively on assessing the success of fiscal adjustment strategies, omitting the fundamental aspects of the quality and effectiveness of public spending. Certain questions have barely even been tackled. I would like to mention three, beginning with measurement of the output of public services.

How to measure the output of public services?

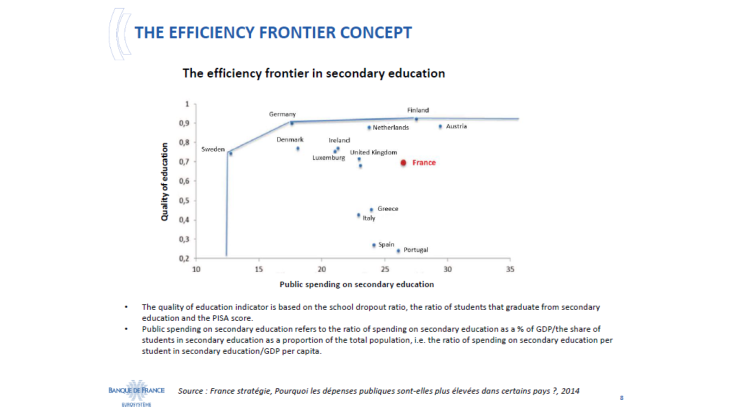

The inherent lack of a selling price for non-market public service output has never really been overcome, and national accounting uses a simplistic arrangement to get around this, consisting of measuring it as the sum of production costs[vii] - in other words, mainly public employee remuneration. This basically means that the only way to increase public service output today is to increase costs and the number of public employees. But how can we gauge the effectiveness and quality of public spending and public services without having any visibility over their 'real' output? The concept of the "efficiency frontier", part of a nascent research field that is little used in France, may provide a partial answer to this question.[viii] It involves comparing the relationship between each type of public spending and one or more international performance indicators (for example, the PISA scores for education) between different countries. However, this remains a little-known, insufficiently operational concept with recurring methodological difficulties for comparing public spending between different countries.

How to interpret fiscal multipliers?

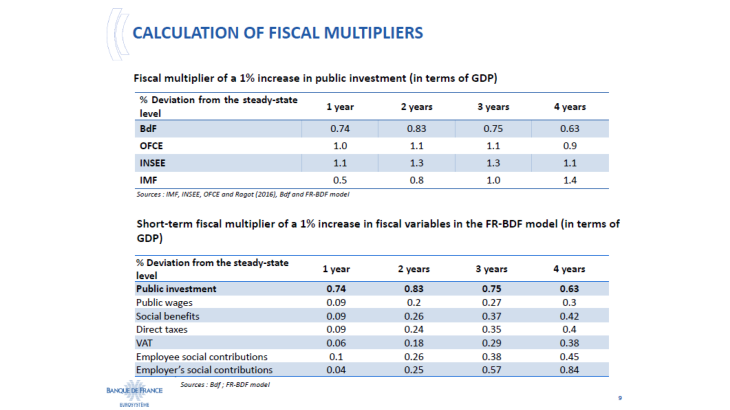

Another area of economic research providing a greater body of work is the calculation of fiscal multipliers. The effect of a fiscal measure on the economy varies depending on the channel used (public expenditure or tax), how it is financed (whether debt is used or not), whether there is a short- or medium-term time horizon, and, obviously, according to the type of spending concerned. However, we are struck by the disparity and fragility of estimates of the same multiplier, which can double in size, depending on the method used. This means there is a risk that everyone uses these concepts in a way that serves their political preferences: certain people advocate tax cuts while others want to increase spending. In truth, few people possess the wisdom to put these multipliers into perspective and analyse them in greater detail, instead of betting time and time again on – supposedly self-financing – fiscal stimulus measures.

How to define “future expenditure”

More broadly, it is still difficult today to formally calculate productive or "future" expenditure, i.e. spending that would have the most favourable long-term effects on economic growth and output capacity or on the climate transition. A consensus appears to be emerging in economic research literature whereby spending on public investment has a more positive effect on growth than operating expenditure. For example, according to our internal models, medium- and short-term multipliers are higher for public investment than for public sector wages. But would this also be true in respect of expenditure on any roundabout or multimedia centre? There is fierce debate around what exactly investment or productive capital actually includes: “basic” infrastructure like roads, bridges and airports generally form the common denominator, to which building construction is sometimes added. “Social” infrastructure such as education or public health facilities constitute another potential category of productive expenditure: investment in education and skills boosts labour productivity and the economy's innovation capacity. More recently, “digital” infrastructure has sometimes been included in productive expenditure, albeit with less clearly defined boundaries, and before us the enormous challenge of artificial intelligence.

This list of questions without answers may appear frustrating.

But it is also, primarily, a call for more research, and Paris should be a centre of excellence here thanks to institutions that are pioneers in this area (France Stratégie, OECD in the international arena, etc.). As with other areas of economic policy, research in this field can help drive the action which I want to speak about next.

III. And yet, it is still possible to transform public services

The key issue with operating expenditure

Neither our strategic review of the past few decades nor economic research offers much hope for progress. This leaves one way forward, namely practitioners and their commitment on the ground. I will therefore now focus on government operating expenditure, which is used in particular to produce major public services. It is sometimes argued that the deterioration in the public finances is primarily due to high amounts of social protection expenditure and transfers, which amounted to approximately EUR 900 billion[ix] in 2022, or 34% of GDP. Operating expenditure is far from being negligible: it accounts for almost a third of public spending (EUR 475 billion, or 18% of GDP) and is therefore a significant potential source for improving public sector efficiency. Central government and national agencies account for EUR 200 billion of this amount, but local authorities with EUR 155 billion account for an increasing proportion.

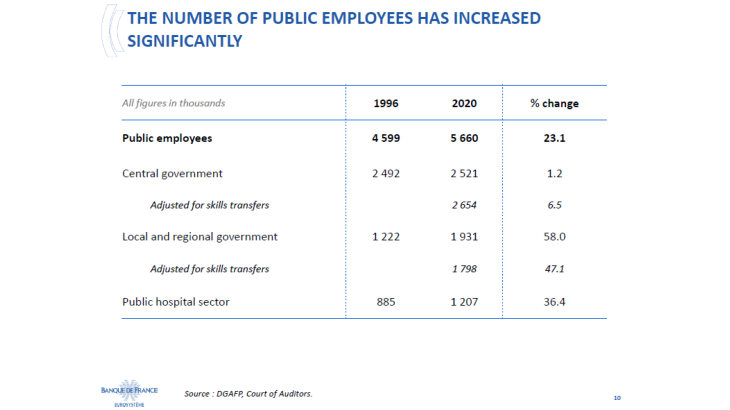

When measured in terms of number of public employees, resources have steadily increased over time. According to the Cour des Comptes,[x] the number of public sector employees grew by more than one million between 1996 and 2020, i.e. an increase of 23% driven largely by local government (+58%, and still 47% even after adjusting for skills transfers). Consequently, the number of civil servants has grown faster than the number of people in market sector employment (+21%).

Emerging from the crisis in public services

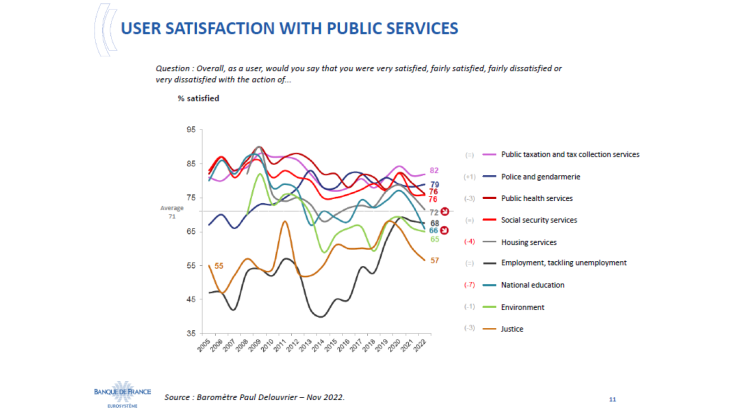

These considerable resources together with the high level of public spending are nevertheless accompanied by a strong impression that public services have actually been deteriorating in recent years. To give just one emblematic example, despite spending 5.2% of GDP on education, France only ranks between 23rd and 25th[xi] among the countries assessed in the latest PISA survey and often compares unfavourably with Germany, which only spends 4.5% of its GDP on education. Too many public services in France give rise to dissatisfaction on the part of those involved - civil servants - users - citizens - and those who finance the services - the taxpayers. These doubts affect essential services such as health, education, justice and the police.

Far from being some fatalistic pessimist, I believe that public services can actually be turned around; not necessarily by increasing resources – which we can no longer afford to do – but as much by an equally important focus on management – I'll come back to these later. These transformations must be effected in liaison with managers and public servants and not in opposition to them: the demands made of civil servants are legitimate; systematic and often demagogical criticism of them is not.

Emerging from the crisis in public services is a matter for the executive - in terms of effective management rather than new legislation. As the Prime Minister rightly declared recently, "the time has come for proof on the ground, rather than legislative cathedral building".[xii] I am well aware of the risk of appearing to give easy or excessively theoretical lessons, but I speak here with the conviction of the practitioner and even - if you will allow me in this last part of my speech - with the passion of the public servant. Public management is not necessarily an easy task, but it is possible. Calling for the transformation of public services today means refusing to become resigned to a public service that is seen as outdated and unable to cope. I believe in the public service as a national asset: throughout our long history, from Bonaparte to Charles de Gaulle, public services have frequently been a catalyst for unity, modernity and even productivity. Transforming public services can and must serve to boost France’s competitiveness. [xiii]

Pious hopes? No! There are perfectly good examples of modernisation of public services here in France, even in the very recent past. We could talk about our army, but I'll start with the current Public Accounts Directorate (Direction Générale des Finances Publiques), formed from the merger of the National Tax Office and the National Public Accounts Office (Direction générale des impôts and Direction générale de la comptabilité publique). This has improved the quality of service provided, especially to private individuals, with the introduction of a sole point of contact for tax matters and the massive development of pre-completed online tax returns, while simultaneously achieving significant economies of scale by pooling support functions (a 6% decrease in financial resources between 2009 and 2016, a 17% decrease in staff numbers over the same period).[xiv] The public taxation and tax collection service currently boasts the highest level of customer satisfaction (82%)[xv]. Withholding tax is one of its most recent major successes.

The Banque de France is another modest example of the transformation of public services; for a number of years, we have been providing more services, reducing costs, while maintaining a nationwide presence. We have increased the services we provide: economic and financial literacy for all citizens since 2016; commitment to green finance since 2017 – here we are recognised as the leading central bank within the G20 -; National Credit Mediation since 2019; a multi-channel offering - including internet and telephone services - for all of our public services. Our cost structure has changed enormously: our total headcount has fallen by 25% since 2015 and our operating expenses have fallen by an average of 3.5% a year in volume terms (constant euro), allowing us to “give back” a total of EUR 200 million to taxpayers in 2022 when compared to 2015 levels.[xvi] Lastly, we have maintained our nationwide presence by committing to keeping at least one branch in each département. This local presence is a prerequisite for public reform, faced with the impression that medium-sized towns are being abandoned. And this is in no way incompatible with generating substantial savings: we are preserving our front offices and contacts everywhere, but we have consolidated all the back offices in interdepartmental shared business centres, thereby achieving substantial productivity gains.

Obviously, the Banque de France is not France and not everything can be transposed. I am sometimes told that we enjoy independence; this is indeed essential for monetary policy and financial supervision, and I should stress the point this year, which marks the thirtieth anniversary of the law of 1993 granting the Banque de France its independence. However, as regards good management, independence is neither sufficient - I even tend to believe that it should require greater exemplarity everywhere it exists - nor necessary: I provided the example of the Public Accounts Directorate. Our experience, along with many others - including those in other countries - can therefore be a source of hope from which I believe we can identify four levers for change.

Taking pride in our missions, and their objectification

Everything starts with clarification of our missions: pride means being able to explain what concrete services we provide to our fellow citizens. Fortunately, these missions are determined not by ourselves but by the political powers that be, i.e. Parliament and the government. However, the missions need to be restated in a way that is intelligible and visible for our fellow citizens - the Banque de France is communicating more than ever about what it does - and results need to be measured - which, as I have said, is more difficult in the public sector.

At the Banque de France, we have resumed and extended the practice of strategic planning: after "Ambition 2020", we prepared "Building 2024 Together". We have set ourselves 10 key results targets and set quantified targets for each of the 30 priority actions.

Accountability for resources

Once these objectives have been defined, it is time for the crucial phase of effective implementation. To this end, the central tool for effective governance is contractualisation with the management team; demanding standards are balanced by delegation of responsibilities. At the Banque de France, each Director General is in charge of his or her own staffing, overheads and investment budgets, both on an overall and a multi-year basis over the plan horizon. This allocation- and contract-based approach is largely transposable to central government ministries and large state administrations. The 2004 Camdessus Report[xvii] already recommended going in this direction. In 2008, the Attali Commission - of which I was a member – specifically adopted as one of the 20 major proposals contained in its report[xviii] the promotion of "agencies". Once the minister concerned had appointed each director, they could draw up a contract of objectives and means whose results could be tracked to ensure accountability. This approach is widely practised in Sweden and elsewhere, and requires no legal changes. Why not start experimenting it straight away? By way of examples, the Attali report cited the tax and accounting administration, INSEE, civil protection and the prison service.

Support for managers

These increased levels of responsibility and autonomy must be accompanied by a change in managerial culture to one that is more open and participative with a cross-cutting focus. When it comes to change management, we never spend enough time listening to and informing the men and women working in the public service, nor do we devote enough resources to supporting them day-to-day. Social dialogue, when it manages to get beyond posturing, can provide one of the levers for change. This support is particularly important for "middle" or local managers: they are the link between senior management and public service workers, and recognition and empowerment are crucial. For example, every year we bring the top 600 managers at the Banque de France together to discuss the progress of our strategic plan. We have given them more leeway when evaluating their teams or organising teleworking, backed up by feedback as often as possible.

Simplification

Lastly, simplification is an essential vector for transforming public services – expected by everyone but all too often neglected. Unfortunately, the law of entropy gets in the way, with ever more complex legislation and administrative procedures.[xix] This complexity hurdle primarily hurts the most insecure and vulnerable groups.[xx] This situation is detrimental to inclusion and trust as well as to our country's competitiveness and attractiveness: an abundance of regulations reduces competition, discourages entrepreneurs and hampers productive investment. We need to learn to regularly "take a broom" to those constraints that are vestiges of the past or which are no longer useful. This requires a massive, structured and costed simplification drive. The recent announcement by the Minister of Transformation and Public Services[xxi] of a plan to simplify procedures for citizens at ten key moments in their lives is a step in the right direction.

To be able to simplify processes, we also need to invest in the digitalisation of tasks and applications: these can represent a crucial source of innovation and time saved for employees.

Alas, the most telling example of administrative complexity can be found in the territorial organisation of our public action, which now comprises a whole stack of departments and local levels, characterised by overlapping responsibilities. The least we can say is that this situation is "not conducive to improving the service provided to households and businesses, nor to making public action more efficient".[xxii] There is widespread dissatisfaction with the loss of responsibility - who gets to decide what? - the time lost and the additional costs. But nobody, from central government to various locally elected representatives, appears ready to give up ground. Is it illusory, for example, to dream of the principle of one entity being in charge of one area of expertise? It may be instructive to take a look at how the Germans make their federalism work in practice.

To conclude, yes, there is still hope... because, as Paul Éluard so aptly put it, "There is another world, but it is inside this one"... especially if we combine a number of ingredients – in which I firmly believe – to cure our current democratic malaise. (i) First, a long-term perspective and perseverance, free from short-termism; (ii) a focus on ex-post results, rather than merely surrendering to the tyranny of media announcement effects; (iii) clarity of responsibilities and management autonomy, rather accumulating expertise and creating ‘rival power bases'; (iv) and mutual enrichment between academic reflection and economic action - I see this as a positive thing for monetary policy, and I hope it will be for transforming public services. And what better place for believing in these things than right here in the Académie des sciences morales et politiques? Thank you for your attention.

[i] Sauvé, J.M., Où va l'État ?, Speech, Conseil d’Etat, 8 April 2013.

[ii] de Tocqueville, A., L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution (1856).

[iii] Cabrespines, J.L., Étude d’impact : mieux évaluer pour mieux légiférer, French Economic, Social and Environmental Council (CESE), 10 September 2019.

[iv] Tirole, J., Economie du bien commun, 2016.

[v] Bacache-Beauvallet, M., Où va le management public ? Terra Nova, 2016.

[vi] Aghion, P., Roulet, A., Repenser l’État, Pour une sociale-démocratie de l’innovation, 2011.

[vii] Carnot, N. et Debauche, E., Dans quelle mesure les administrations publiques contribuent-elles à la production nationale ? Insee Blog, 2021.

[viii] Mareuge, C. et Merckling, C., Pourquoi les dépenses publiques sont plus élevées dans certains pays ? France stratégie, 2014; see also IMF, France: 2022 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for France, 30 January 2023.

[ix] Insee, Le compte des administrations publiques en 2022, 31 May 2023.

[x] Cour des Comptes, La situation et les perspectives des finances publiques, July 2022.

[xi]Three averages for the major subjects tested (reading comprehension, mathematics, science). OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris

[xii] Borne, E., Rencontres des cadres dirigeants de l'État, speech , 17 May 2023.

[xiii] Villeroy de Galhau, F., « Comment la France et l’Europe vont vaincre l’inflation », Letter to the President of the French Republic, April 2023.

[xiv] Cour des comptes, La DGFiP, dix ans après la fusion, 20 June 2018.

[xv] Baromètre - Institut-Paul-Delouvrier 2022

[xvi] Banque de France, Annual Report 2022, 22 March 2023.

[xvii] Le sursaut, Vers une nouvelle croissance pour la France, working group chaired by Michel Camdessus, 2004.

[xviii] Rapport de la Commission pour la libération de la croissance française, 23 January 2008.

[xix] Conseil d’Etat, Simplification et qualité du droit, annual review, 25 September 2016.

[xx] DITP, Baromètre BVA de la complexité administrative et de la confiance en l’administration par évènement de vie, 24 May 2023.

[xxi] Commitment No. 3 of the 7th Interministerial Committee for the transformation of public services of 9 May 2023.

[xxii] Cour des comptes, La décentralisation 40 ans après, Public Annual Report 2023.

Updated on the 21st of November 2023