- Home

- Governor's speeches

- Monetary policy in the euro area: was it...

Published on 25th of September 2023

ECB – CEPR – Banque de France Conference – Paris, 25 September 2023

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Ladies and gentlemen,

It is my great pleasure to welcome you to the 'Monetary Policy Challenges for European Macroeconomies' conference. As you know the conference is jointly organised with the European Central Bank, CEPR and the Journal of Monetary Economics. The programme features some of the most distinguished economists in the field of monetary economics, and I would like to welcome in particular my colleague Philip Lane, the Chief Economist of the ECB, who will give a speech tomorrow, and our two keynote speakers, Hélène Rey and Jordi Gali. Central bankers are always eager to learn from academics: we need high quality research to provide good policy.

The conference aims to present recent studies with a focus on European questions. It is a welcome initiative as an overwhelming majority of applied macroeconomic research focuses on the US. This is for understandable reasons, given the size of the US economy, but I daresay that European questions are really worth exploring further. First, the euro area is the world’s third largest economy. Second, and most importantly, the euro area constitutes a unique endeavour, in which 20 countries have freely and peacefully decided to unite their efforts and create a joint currency. This currency union will celebrate its 25th anniversary next January. It has resisted severe stress tests – most recently Covid and war – and has garnered ever increasing popular support: today 78% of citizens in the euro area support our single currency, up from 68% in 1999. Despite its remarkable success, the largest currency union in the world gives rise to specific economic challenges. In the remainder of my talk I will elaborate on the current situation in the euro area, looking back at the inflationary episode that started in 2021.

To set the scene I would like to discuss two criticisms that have been directed at our monetary policy (and other central banks’): (i) we allegedly reacted too late when inflation started to rise; (ii) we could run the risk of doing too much today.

1. “Too late”

This criticism comes in two parts: that the ECB erred in 2021 by judging that the surge in inflation in 2021 was temporary, and then was too slow to end net asset purchases and raise policy rates in 2022. Of course, knowing what we do know ex-post, some decisions could have been taken a few months earlier. However, I do not think, looking back, that we could have done a lot better in real time.

The discussion about “temporary”

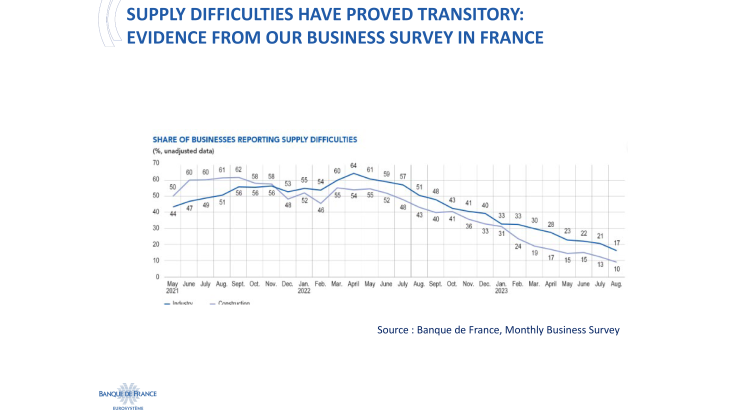

First, regarding the question of whether the inflation surge was temporary, it is worth recalling the obvious. We were hit twice: first by supply bottlenecks following the post-covid reopening in a context of high excess savings, and then the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The textbook answer to the first negative supply shock was looking through, as long as long-term inflation expectations remained anchored. A large majority (around 75%) of respondents to a Banque de France survey of firms in early February 2022 believed that their difficulties in supply would disappear in the following 12 months[i]. The underlying supply bottlenecks in goods markets did indeed prove to be transitory, and domestic producer prices are now falling.

It is a reasonable criticism ex-post that “looking through” this original shock left the economy vulnerable to a second inflationary shock but we had just been through a decade of below-target inflation, and policy rates were stuck at the effective lower bound. The risk of falling back into another low-flation equilibrium was very real. The academic debate at that time was also very divided [ii] [iii].

This strategy was, of course, completely upended by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the resulting dramatic increases in energy prices (which rose by 29% from January to October 2022) and food prices (which rose by 12% over the same period). These two components alone contributed 6.8 pp to headline inflation in October 2022. But even then, no one was quite certain how these shocks would play out, in particular as this represented a large and negative terms of trade shock for the euro area, unlike the United States.

But the decisive change was that the dynamics of inflation shifted from these specific external factors to broader and more domestic sources. Core inflation (as measured by HICPX) rose from 3% in March 2022 to 5.5% in July 2023. Inflation was not only higher, it became more broad-based from a strong shock on relative prices to a lasting change in prices in general. It is here, in spring 2022 that the risk of a persistent inflation became obvious.

Was our monetary reaction too weak?

Given this shifting balance of risks, did we react too late and too slowly? Here, too, we shouldn’t forget a number of points.

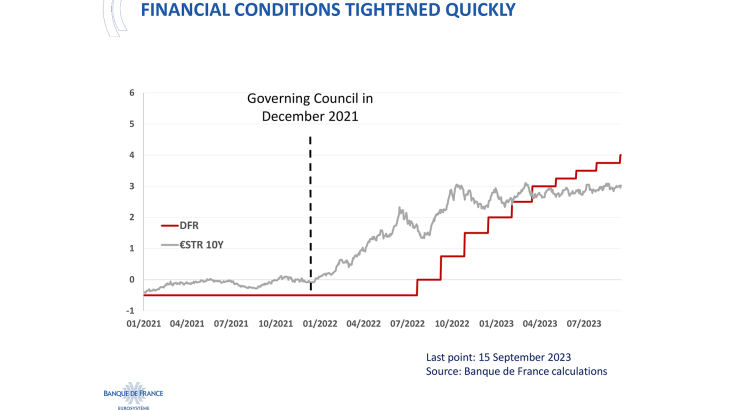

A first point to make is that beyond policy rates, what matters is how the current and expected policy stance affect the financing conditions faced by firms and households. This slide illustrates the deposit facility rate (DFR) and the 10 year OIS rate.

This shows that the stance was already tightening quickly from December 2021 onwards. As early as then, we announced our intention to end net asset purchases under the PEPP and to slow the future pace of net purchases under the APP. And we confirmed and detailed our decision in March 2022: believe me, it was not such an obvious one, three weeks after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and looking at market expectations and many public suggestions. The 10-year interest rate had already risen by around 150 basis points before the deposit facility rate (DFR) was increased in July 2022.

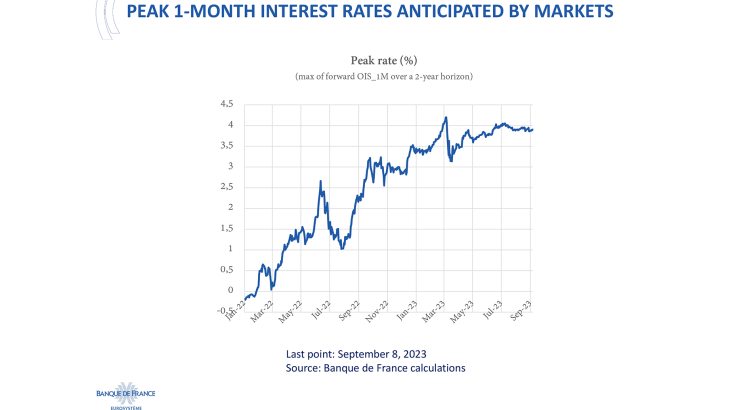

A second point is made by the following slide. This presents at each point in time the peak 1 month OIS rate (at any horizon) implied by the market. This shows that when Russia invaded Ukraine, the peak interest rate expected by markets was around 0.75%. Even in August 2022, the peak rate was not much more than 1% and not until January 2023 did the peak rate exceed 3%.

Admittedly, it shows that markets were slow to adjust their expectations, just like anyone else. But it also demonstrates, in a more subtle way, that markets and financial institutions have believed that monetary policy was always on track to return inflation close to target, and trust the European Central Bank.

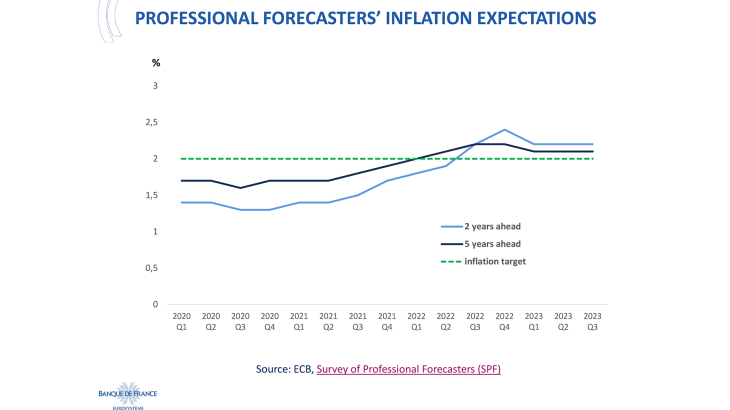

What is more, professional forecasters’ inflation expectations have remained broadly anchored, both 2-years and 5-years ahead; their mean points now stand at 2.2% and 2.1% respectively, consistent with our inflation target.

Of course, since July 2022 we have raised rates far more than was originally anticipated, but that shows the extent of the data surprises between then and now. At 4%, the policy rate – DFR – has been raised by 450 basis points since July 2022, a rapid tightening of monetary policy almost unprecedented by major advanced countries over the past 40 years.

One useful lesson on forward guidance

Critics are largely arguing with the wisdom of hindsight. That said, looking back, there is probably one useful lesson. Our reliance on forward guidance on rates was perhaps excessive in principle in the face of exceptionally large and unexpected shocks, and too rigid in its substance. As I have said previously,[iv] we cannot totally bind our hands with rules, and should keep some element of discretion facing unexpected data or events. Forward guidance is never setting policy on auto-pilot. There will always be an element of judgement, including about the distribution of risks around the staff projections. Central banks should be predictable, but not pre-committed. Lift-off from the effective lower bound was double-locked, being both state contingent (three inflation criteria) and sequenced after the end of net asset purchases. With more flexibility, the first interest rate increase could have occurred earlier than July 2022; but it is unlikely that this would have been more than one or two meetings before. In the grand scheme of things, it would not have changed very much because financial conditions had already anticipated future rate increases through an increase in medium- to long-term interest rates. In the future, I wouldn’t rule out a certain return to forward guidance, but seen as more indicative, more state-dependent… and more modest – i.e. less powerful as an instrument.

2. Now, “too much”?

The alternative criticism is not about the past but about the present situation, i.e. that we would have already done too much and run the risk of tipping the economy into recession. I will not focus on the discussion of our last 25 bp hike on September 14. While I can fully understand this discussion, my analysis is of our broader 450 bp increase since July 2022.

Some good news…

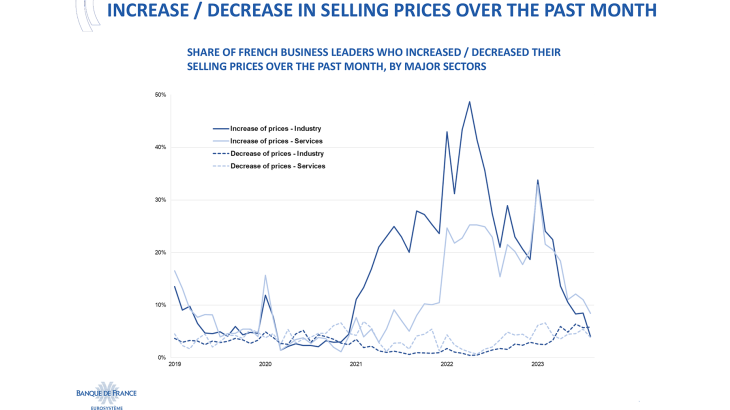

Headline inflation has already fallen back from its peak of 10.6% in October last year to 5.2% in August, and strangely enough this criticism contains elements of good news. Firstly, it implies that monetary policy has indeed had a powerful effect on the economy. Not so long ago, there was a debate about whether the IS curve had become fairly flat and our instruments were weak in combatting inflation. Second, it shows, at least in several countries including France, that the inflation psychology has switched, with receding concern over upside inflation risks. Our resolute monetary policy over the past year was indeed intended to break a self-sustaining inflationary psychology. Households’ and firms’ inflation expectations have peaked, supporting this assessment. Our latest monthly business survey, released a week ago[v], shows that business leaders are adapting their selling prices accordingly. For the first time in August, the share of industrial firms that have decreased their selling prices (6%) is larger than the share of firms that have increased them (4%).

… but risks to be rightly assessed

However, the criticism that we have done too much misses two points in my opinion. It somewhat overestimates the risks to growth: what we presently see – and forecast – is a slowdown, not a recession; and employment remains at record highs, which is a positive surprise. And it underestimates the persistence of inflation. Headline inflation has indeed come down rapidly. But regarding underlying inflation, the news is less clear-cut. The HICPX rose to 5.7% in March this year but fell back to 5.3% in August. In the Eurosystem, we look at a battery of indicators and those that try to identify instant inflation are lower than this, below 3%; they all point in the right direction. Nevertheless, annual nominal wage growth remains sustained, although showing early signs of peaking: it is forecasted to reach in average 5.3% in the euro area in 2023, and 4.3% and 3.8% respectively in 2024 and 2025.

Furthermore, some commentators talk about “the difficulty of the last mile” in the return of inflation back to the 2% target. However, this phrase supposes non-linearities in the Phillips curve, which have not been really identified in the European case. And some suggest that as a result we should accept that “near-enough”, say 3%, is close enough to target rather than set a much tighter policy in the pursuit of 2%. I am not fixated on 2.0% to the nearest decimal place, but I do believe that it would be very counterproductive to change or relax our inflation target, either explicitly or implicitly.

One lesson about the future

Just like the criticism about the past, this unwarranted criticism can nevertheless serve a useful lesson. The risk is not that we have already done too much. It is possibly that we could do too much in the future. Let me elaborate with some personal reflections.

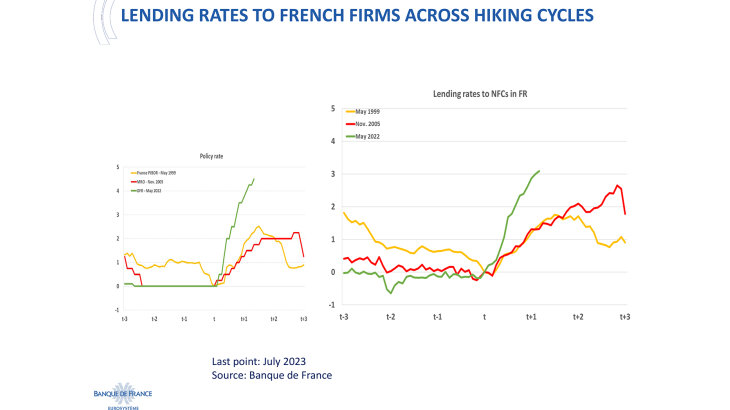

First, we should take into account the very strong and fast transmission of our monetary policy tightening to financing conditions. The following slide shows the very rapid increase in the policy rate relative to previous tightening cycles on the left and the corresponding sharp increase in lending rates to non-financial corporates (which have risen by around 300 bp since May last year). If anything, this transmission has been even faster than we expected.

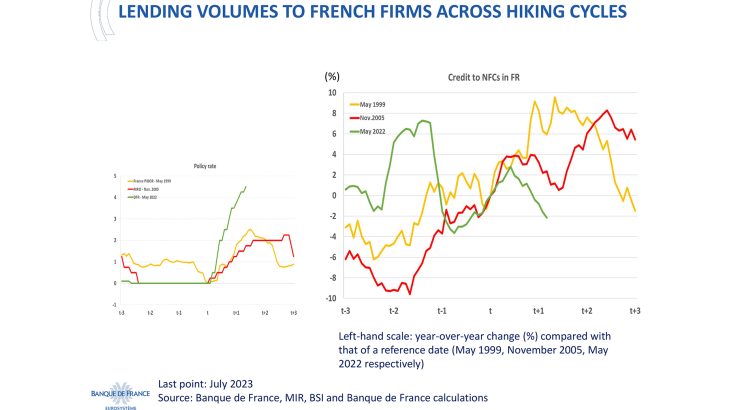

Bank deposit rates have also risen, more so for term deposits, triggering a reallocation towards the latter. The volume of credit outstanding to firms has slowed sharply and faster than in previous tightening cycles.

However, there is still more transition to come as fixed-rate loans roll off and are renewed at higher rates. This process takes time and we at the Banque de France estimate that there could be still between 40 and 50 basis points of increase in lending rates to non-financial companies yet to come. A last word on monetary transmission: while its ‘first leg’ (to financial conditions) is obviously quick, we are less clear at this stage about its second leg (from financial conditions to the economy)[vi].

Second reflection: we clearly have a primary objective, which is our destination, bringing inflation back towards 2% by 2025. There can be no doubt about our determination and commitment. We have growing confidence in achieving this – see our latest forecast about 2025 inflation. And hence, subject to this primary objective, we can now incorporate a secondary one concerning the path: if we can reach the destination with a soft landing rather than a hard one, it’s a much better route, for the economy, for our fellow European citizens, and for the sound conduct of fiscal policies.

The risk of doing too much needs to be balanced against the risk of not doing enough. In my judgement, these risks are now at least symmetric. In the latter case, inflation would remain persistently above target and inflation expectations might become de-anchored. This is a manageable risk because we always can do more if the risk materialises. But in the risk of doing too much, with the economy falling into recession and causing a sharp deceleration of inflation, we would then have to rapidly reverse course. Hence, “testing until it breaks” is not a sensible way to calibrate monetary policy. This suggests that we should now focus on the persistence of policy rather than the constant pushing of rates higher – duration rather than level.

Patience and persistence in monetary policy does not mean inaction. Our current stance is restrictive – market implied real rates are above our estimates of the neutral rate – so maintaining the current level will bring down inflation. In the same way that there is a risk of doing too much in the future, there is the opposite risk of easing too early. If markets fully incorporate our persistent strategy, they shouldn’t expect rate cuts before a sufficiently long period of time; then markets will endogenously extend the duration of elevated rates, contributing to the appropriate calibration of the stance. In any case, our policy should remain data dependent. In particular, we have to monitor closely the recent rebound in oil prices. At present, it’s far from a general commodity shock like in 2021-22; but we have to monitor its possible effects on inflation expectations and wages: underlying inflation remains our key indicator. A persistent strategy is not a forward guidance that rates will never increase again. It remains a pragmatic strategy: and as a pragmatist, I clearly stress today that “based on our current assessment, we consider that our key ECB interest rates have reached levels that, maintained for a sufficiently long duration”, are broadly consistent with the timely return inflation to our target, that is 2025.

To conclude, in the last three years we had to navigate among unprecedented uncertainty. It would be ridiculous to pretend that we have always been 100% right, but as a whole we dealt with data and surprises in a skillful manner. We now know with growing confidence that we are on the right track, towards our 2% inflation target. However, still accepting this uncertainty is, if not what science is typically associated with, at least what rationality commands. As the British mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote, “not to be absolutely certain [is] one of the essential things in rationality”.[vii] I thank you for your attention, and wish you a good conference.

[i] Banque de France, Point sur la conjuncture française à début février 2022, February 2022

[ii] Reichlin, L., Ricco, G., Mc Mahon, J., Understanding inflation risks in the US and the euro area, 22 December 2021

[iii] Ilzetki, E., Surging inflation in the UK, 10 February 2022

[iv] Villeroy de Galhau, F., Monetary policy in uncertain times, speech at London School of Economics, 15 February 2022

[v] Banque de France, Monthly Business Survey, 18 September 2023

[vi] Villeroy de Galhau, F., Monetary policy transmission: where do we stand?, speech, 22 May 2023

[vii] Russell, B., 1947

Updated on the 21st of November 2023