Challenges and outlook for the green bond market

This market is a key focus for many central banks amid questions surrounding the financing of the transition to a net-zero economy and consider the role monetary policy can play in this (Dees, Ouvrard and Weber, 2022, Villeroy de Galhau and Dees, 2022). The fight against climate change is a key issue when it comes to monetary policy. First, in terms of central bank price stability mandate, given that the transition to a greener economy could put upward pressure on prices (see Schnabel 2022). Secondly, through the incorporation of ‘greener’ criteria into monetary policy tools (refinancing operations, collateral rules, asset purchase programmes, see the report published by the NGFS - Network of central banks and supervisors for Greening the Financial System).

In parallel, some issuers see these instruments as an opportunity to send a powerful signal to the market that they are working to combat climate change, one that could eventually broaden their investor base, improve reputation, and secure a cheaper source of financing (higher bond prices and lower yields). A number of studies have been conducted to determine whether green bonds trade at a higher price than conventional bonds (and therefore carry lower yields, i.e. a ‘greenium’). While the findings vary for the market as a whole, given how hard it is to compare securities, Pietsch and Salakhova (not yet published) have found evidence since the Covid crisis that suggests a statistically-significant ‘greenium’ for euro-denominated green bonds.

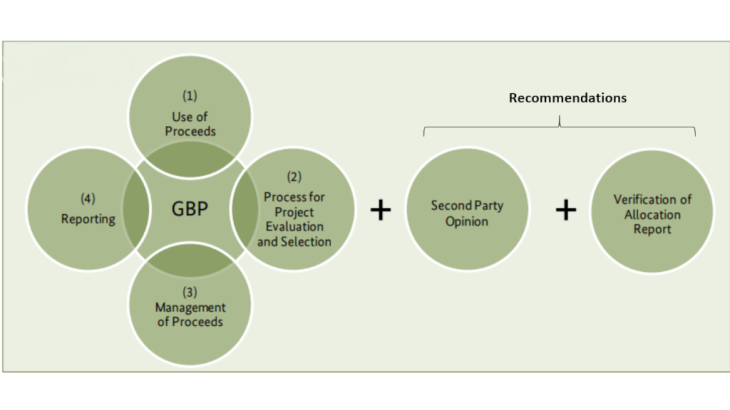

However, the appeal of this market and the fact that there is no binding regulatory framework for green bonds may lead to suspicions of ‘greenwashing’ (false green claims). In order to provide a better framework for green bond issues, the European Union is currently working on an EU Green Bond Standard and a European taxonomy. The EU Green Bond Standard draws inspiration from the GBPs and introduces more stringent transparency and external review requirements. The EU Taxonomy defines a list of sustainable economic activities aiming to better direct investments towards activities aligned with the Paris Agreement (the delegated act should enter into force in mid-2022).

How the market react to this new body of regulations is still unclear as some investors may opt for other debt instruments fearing of being legally exposed if they fail to comply with the requirements. As evidence of this, some analysts have been seeing strong growth in Sustainability-Linked Bonds since 2021. These debt instruments are linked to more general sustainable development goals, which may not be deemed as restrictive as those set for green bonds.